In this week’s article, we discuss capturing value from volatility, and in the process, talks about WeWork, Uber, Virtu Financials, and Robinhood:

Volatility can’t be destroyed, just transformed

First proposed by Émilie du Châtelet, the first law of thermodynamics states that, in an isolated system, energy cannot be created nor destroyed. It can only be transformed from one form to another. For example, if you burn gasoline while driving your car, you are converting chemical energy into mechanical energy (plus heat and noise), but the total energy is conserved.

Unlike energy, volatility can be created (by using leverage for example), but it cannot be destroyed. So the second half of this law also applies to volatility. This is true in markets and in labor forces. Although it cannot be destroyed, volatility can be smoothed out or transformed, and there is much value in doing so.

Generally though, there are two ways you can extract revenue from volatility – by smoothening/transforming it, or by monetizing it.

Transforming volatility

The idea of smoothing or transforming volatility is not new – in fact it underpins much of commodity trading. Smoothing volatility in commodity trading is done via futures contracts. Futures contracts are legal agreements to buy/sell commodity or securities assets at a predetermined price at a specified time in the future, thereby removing future uncertainty.

A futures contract is an old concept. In fact, the first recorded forward contract in the US was in 1851. A famous example of a product enabled by futures contract is McDonald’s Chicken McNuggets. As the story goes, Ray Dalio enabled McDonald’s to launch Chicken McNuggets by creating the first chicken futures contract that allowed McDonald’s to launch the nuggets without worrying about the volatility of chicken prices.

Smoothening of volatility also happens in the technology sector. Many tech companies create value by transforming high volatility assets into low volatility ones. However, while this tends to work ok when the volatility is accompanied by increased valuation of the asset (the tech company can profit on the upside), it becomes unprofitable when it goes the opposite direction. Here are a few examples.

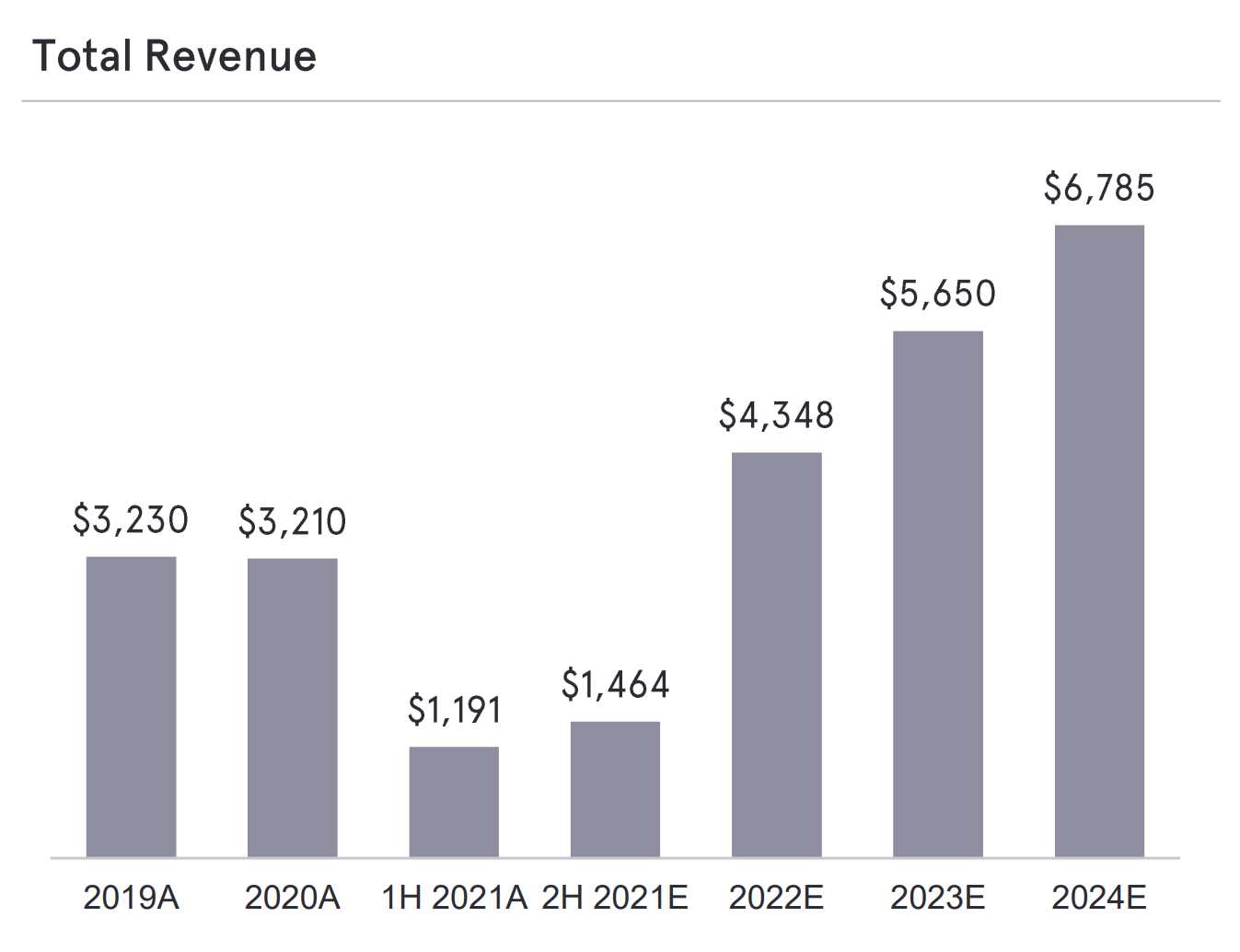

WeWork – rent long and sublease short – absorbing volatility in rent prices

WeWork’s core value proposition in the office rental space is allowing customers to sign flexible short term rentals, while the company itself signs long term leases with property owners. For the increased flexibility, WeWork charges its customers more on a per square foot basis, and on the other side of the equation, signs lower cost leases with landlords by promising long term contracts (the average lease length is 15 years). This effectively means that WeWork absorbs the volatility in rent prices for the landlords by signing longer leases, while increasing revenue volatility for itself. This is all great when the economy is growing and people are looking for office space to rent. But it is really bad when a recession happens (and doubly bad when there’s a global lockdown). The company is SPACing soon, so it’s disclosing its revenue numbers (which you should digest with a large grain of salt).

Uber and gig workers

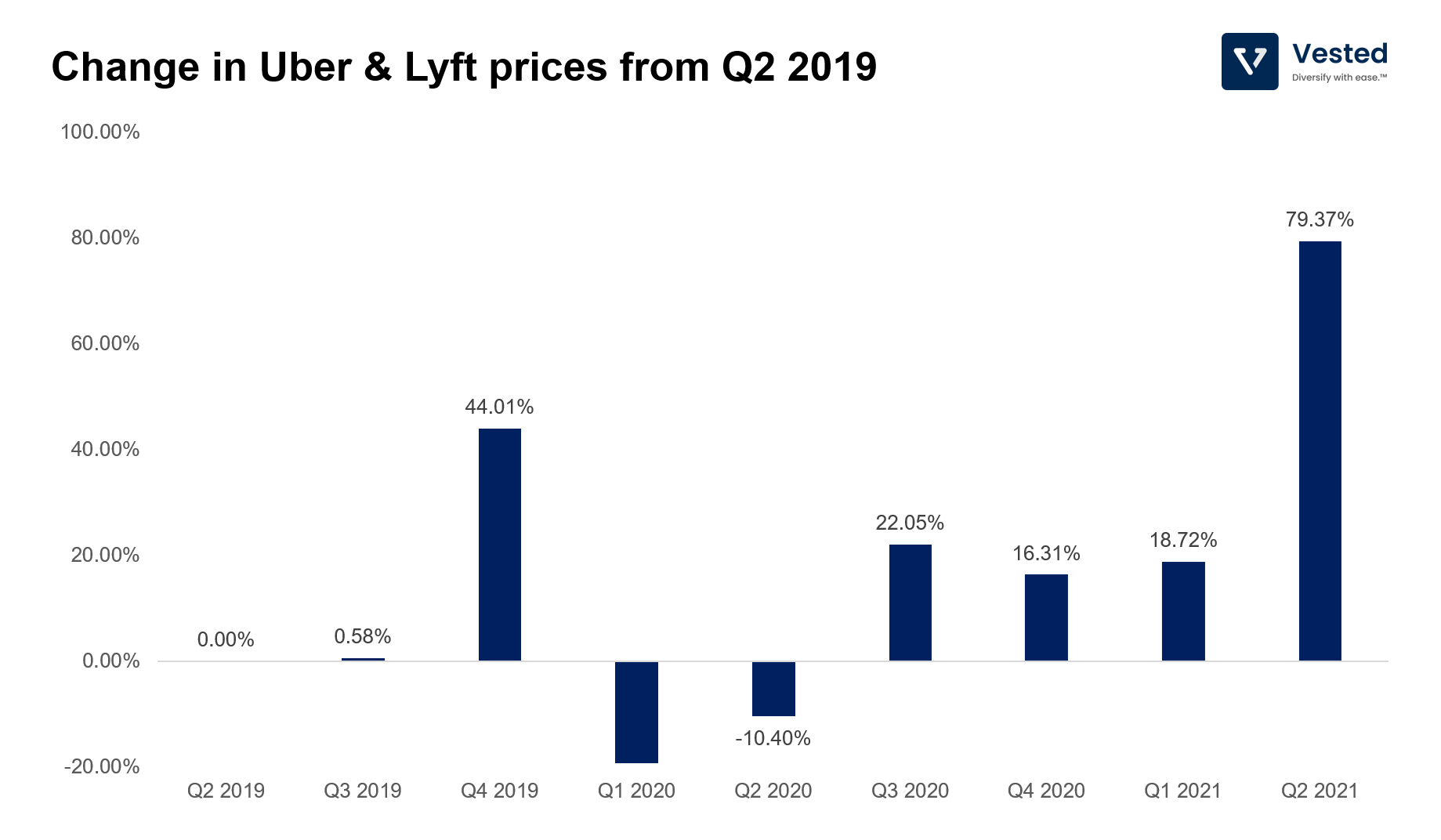

Another way tech companies carry out volatility arbitrage is by transforming long term labor costs into temporary ones. This is what the gig companies do. The flexibility of gig workers means the gig companies assume greater exposure in labor price volatility. Under normal circumstances, this works in their favor. When the economy is bad (and therefore demand declines), Uber/Lyft/Instacart (and other companies like them) are not on the hook to pay salary or severance (if layoffs are involved). But the opposite is also true. When the labor market is tight (and demand is high), these companies struggle to recruit gig workers.

Take Uber and Lyft for example. Both companies are struggling to recruit drivers as the economy is ramping back up. The lack of supply translates to higher surge prices for users (see Figure 2 below). Fares cannot increase indefinitely, however. There’s a limit on how much prices can go up. Once this limit is hit, the gig companies must absorb the difference. Uber fares in the US went up 27% between January and May of this year. Over the same period, drivers’ pay per trip increased 37%. The increase is likely due to increased driver incentives. Earlier this year, Uber announced plans to spend $250 million in increased drivers’ incentives, but it seems the driver supply constraint still persists.

In the two examples above, the companies profit by absorbing and transforming volatility. This is not the only way to capture value, however. There are companies that profit not by absorbing volatility, but rather by monetizing the volatility itself. As such, the higher the volatility, the more money they make. Two companies that do this are Virtu Financials and Robinhood.

Making money from volatility

Virtu Financial

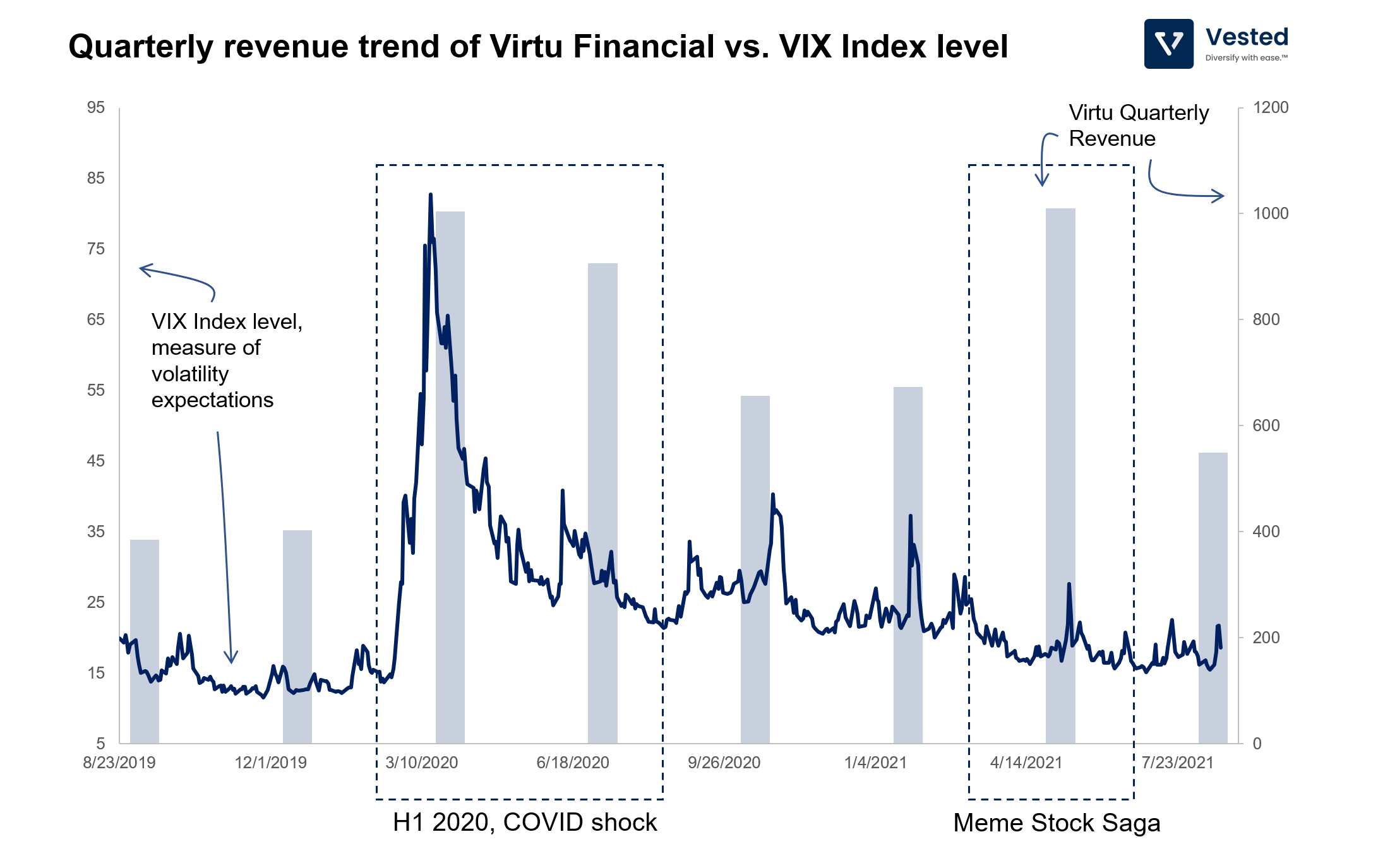

Virtu Financial is part high frequency trading firm, part wholesaler in the equity retail market. A retail wholesaler is a market maker firm that buys order flow from retail brokerages. These firms buy order flow from retail brokerages (such as Robinhood), internalize the trades, and generate revenue as a percentage of bid and ask spread of stock prices, while at the same time, offers price improvements (Virtu claims to have provided over $3 billion in price improvements to retail traders in 2020) over the national best bid offer (NBBO, the national benchmark for prices for public securities).

These wholesalers prefer to purchase retail order flow, since on average, retail traders have no information advantage in the market. When these wholesalers are the counterparties to retail traders, they will not be exposed to asymmetric trades. If, on the other hand, these wholesalers are counterparties to sophisticated investors (hedge funds, Goldman Sachs, etc), they run a higher risk of being run over (what if the hedge fund knows something about the company being traded that the wholesaler does not…). If this is the case, wholesalers have to increase the bid and ask spread to accommodate for this possibility.

Knowing that the order flows you’re dealing with is purely from retail traders is valuable. So much so, that at scale, it is quite riskless for these wholesalers. This is why they can give rebates (payment for order flow) to retail brokerages such as Robinhood, while still providing a tight bid/ask spread that improves on the NBBO.

Virtu and Citadel Securities dominate the US wholesaling business and are the two largest rebate providers to Robinhood.

Because these firms make money based on the trade flow and bid/ask spread width, any increase in volatility (and volume) is good for their revenue. Below shows Virtu’s quarterly revenue trend (see Figure 4). The company experienced significant boosts in revenue during periods of heightened volatility, specifically around the market downturn in the first half of 2020 and in the first quarter of 2021, during the peak meme stock saga in Q1 this year.

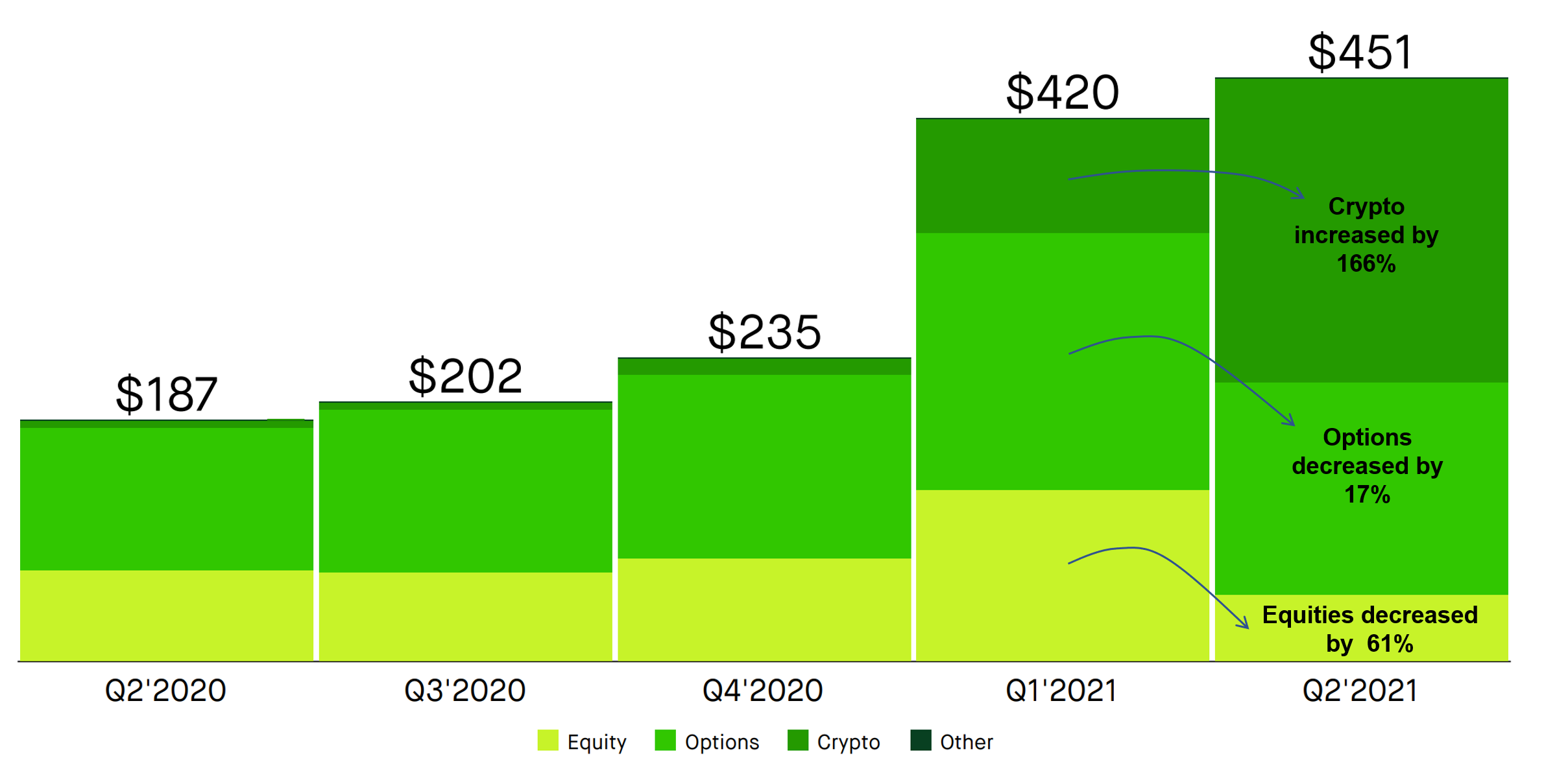

Robinhood’s volatility

One advantage that Robinhood has over Virtu is that it monetizes volatility not only in equity markets, but also in crypto. Robinhood has a more diverse revenue source. In July 2021, it went public at peak retail frenzy. But in Q2 2021, the retail equity activities declined. As a result, similar to what Virtu experienced, transactional based revenue from options and equities flow declined significantly, -17% and -61% respectively! Fortunately, Robinhood monetized from crypto as well. Transactional revenue from crypto trades jumped 166%. You can see these trends in Figure 5.

According to Robinhood’s latest earnings announcement, about 14.2 million Robinhood users, or roughly 63% of the company’s funded accounts, traded crypto in the second quarter. Similar to its equities operations, Robinhood also routes these crypto trades to high speed trading firms (for crypto, the flow goes to New York-based Hudson River). Robinhood earns $233 million in the process, with Dogecoin accounting for nearly two-thirds of the volume. That is up from just $5 million a year ago (dark green bar in Figure 5).

Interestingly, Hudson River also plans to enter the retail wholesale segment. This means it is entering a market dominated by Citadel and Virtu (both have 70% of retail investors’ orders combined). Hudson River itself is quite a large, high frequency trading firm, contributing to about 8% of daily US stock volume.

As we mentioned above, the wholesale business for retail trades can be quite profitable, and involves taking minimal market risk. Increasing competition in this segment will benefit Robinhood. Everyone wants a piece of the retail order flow, and when there’s increased demand on a finite supply, the purveyor of the supply will naturally have more pricing power. And at this point, Robinhood has the largest retail user base. In the end, this can potentially benefit the retail investors, in the form of tighter bid/ask spread and better price improvement.

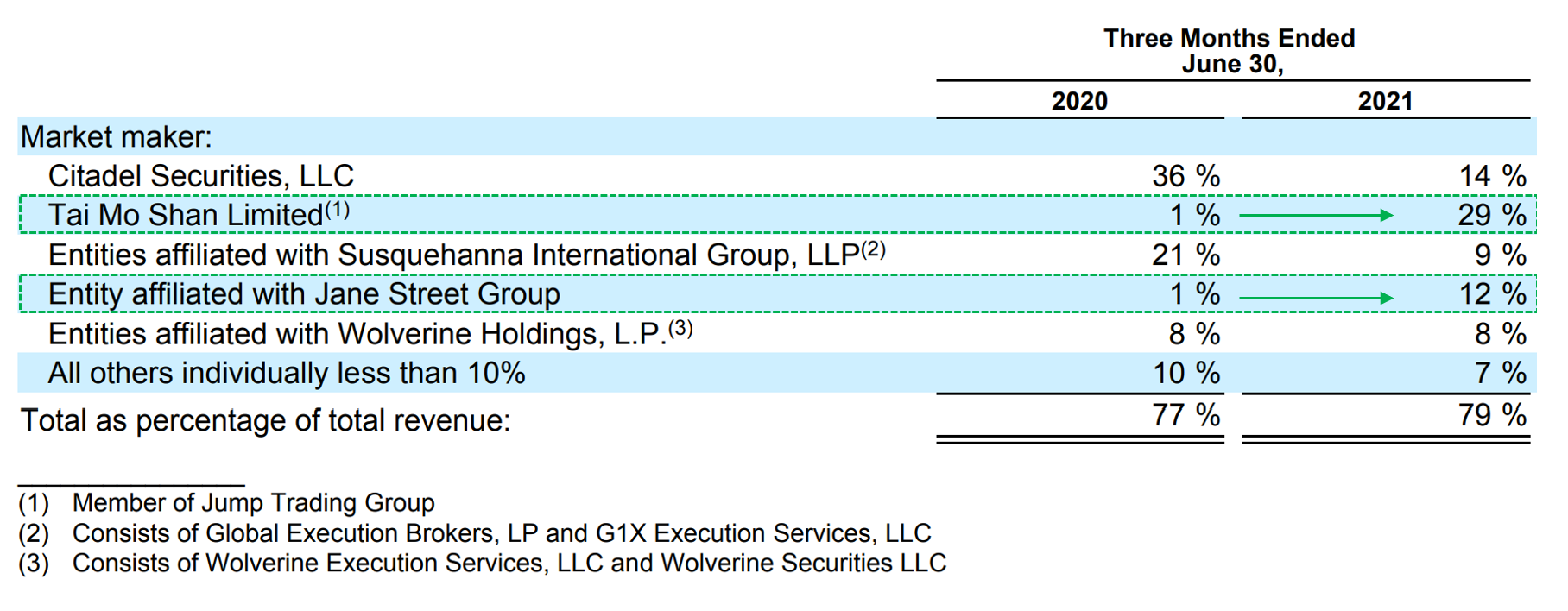

Another indicator that demand for retail order flow from wholesalers is increasing: In Q2 2021 earnings, Robinhood disclosed the different firms it routes orders to, as a percentage of revenue. Notice the large change year-over-year shown in Figure 6 below. To compete for order flows, these wholesalers compete on the rebate amount and execution quality. Tai Mo Shan (part of Jump Trading) is a new market maker for Robinhood that is not part of the big players listed in Figure 3 above but, in short order, has become Robinhood’s largest purchaser of order flow.

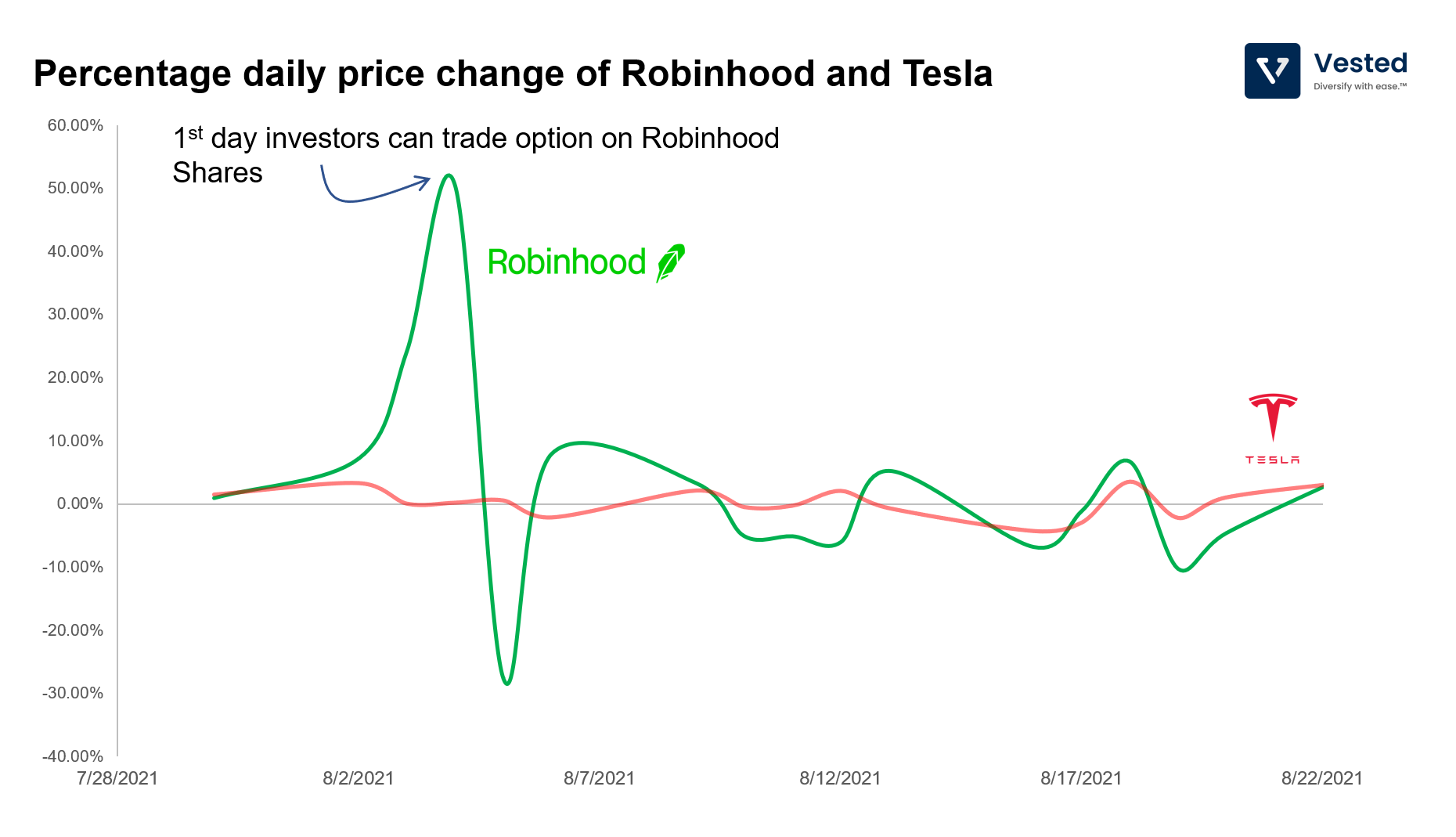

Finally, Robinhood is also unique in that it does not only monetize from volatility. The share price of the company itself experienced heightened volatility. Since the company’s shares started being traded in the options market (and if you recall above, we mentioned that options & leverage increase volatility), the daily change of the share price has fluctuated wildly (green line), much higher than Tesla (red line), the original meme stock (Figure 7). Robinhood itself is turning into a meme stock.

Robinhood is turning into ouroborous of volatility. It helps create volatility (via easy options trading), makes money from volatility (both in equities and crypto), and itself experiences heightened share price volatility.