Ant Group was going public in both the Hong Kong and Shanghai exchanges. Initially, it was slated to be the largest IPO of all time, a fintech firm valued at more than US $300 billion. But out of nowhere, changes in the regulatory environment halted its intended IPO. Now, the company has to restructure its operations before it can try again in either 2021 or 2022.

So what happened? To understand this, let’s take a brief detour and talk about what it means to be a bank.

The old banks

Since its inception in ancient times, banks have operated principally on the same basic framework:

- Role 1: Banks collect deposits from people (or in other words, you lend the bank money).

- Role 2: The banks then lend these deposits to others and charge interest rates.

- Role 3: When these borrowers pay the bank back, plus interest, the bank gives you some of this interest and pockets the difference.

Therefore, one way to modulate a bank’s profitability is to measure how cheaply it can gain deposits. The cheaper it gets its deposits, the higher the margins it can potentially achieve.

Over time, this basic framework has gained additional layers of complexities. The lending business becomes varied, the amount of deposits the banks have to keep (called the reserve requirement) changes over time – as governed by the Central Bank (the Fed), and with increased regulatory complexities, the cost of compliance has started to outpace revenue growth.

The level of complexities that Banks have to deal with have slowed them down. As a result, the financial services landscape is shifting. New entrants masquerading as ecommerce, coffee sellers and others are taking advantage of the same basic framework outlined above, but without the overhead of complexities – to gain deposits and lend out money at lower costs.

In effect, playing the different roles of a bank, without being a bank.

Here are three examples: Starbucks, Affirm (going public soon), and the Ant Group.

Non-banks performing different banking roles

Role 1: Starbucks collects deposits

Starbucks makes money by selling you coffee and an assortment of food, but it also makes money by taking deposits from its consumers.

The company is an innovator in digital payments. It came out with its app in 2009, just 2 years after the iPhone was launched. Through its mobile payment system, consumers can pre-load their account with money. The act of pre-loading cash into your Starbucks wallet is equivalent to lending money to Starbucks at zero interest. Starbucks accumulates these funds. Some portion of this fund is never used, which then becomes revenue for Starbucks. This is called breakage revenue.

In fiscal 2019, consumers deposited almost US $11 billion in their wallets; from this, Starbucks made US $140 million from breakage (or 1.28% breakage rate). This is 8% of total annual revenue.

Talk about finding loose change between the couch cushions.

Role 2: Affirm gives out loans to people

What does Affirm do?

There are several approaches taken by tech companies to give out loans. One such approach is providing short term loans for ecommerce purchases. This is called “Buy Now Pay Later†(BNPL). This is where a technology firm interjects itself in the e-commerce checkout process, offering low (often zero) interest loans to customers making purchases.

One such firm is Affirm, which will be going public in the next couple of weeks.

The BNPL industry is relatively new in the US. In the US, online purchases have been dominated by credit cards, which effectively acts as a buy now pay later mechanism, where you purchase an item and pay your credit card later. BNPL players such as Affirm replace the role of credit cards.

Although still nascent, the BNPL market share is expanding in North America, where it is expected to grow to 3% of e-commerce payments by 2023. Meanwhile in Europe, Middle East, and Africa (EMEA), BNPL constitutes 6% of e-commerce payments, and is expected to grow to 10% by 2023.

How does Affirm make money?

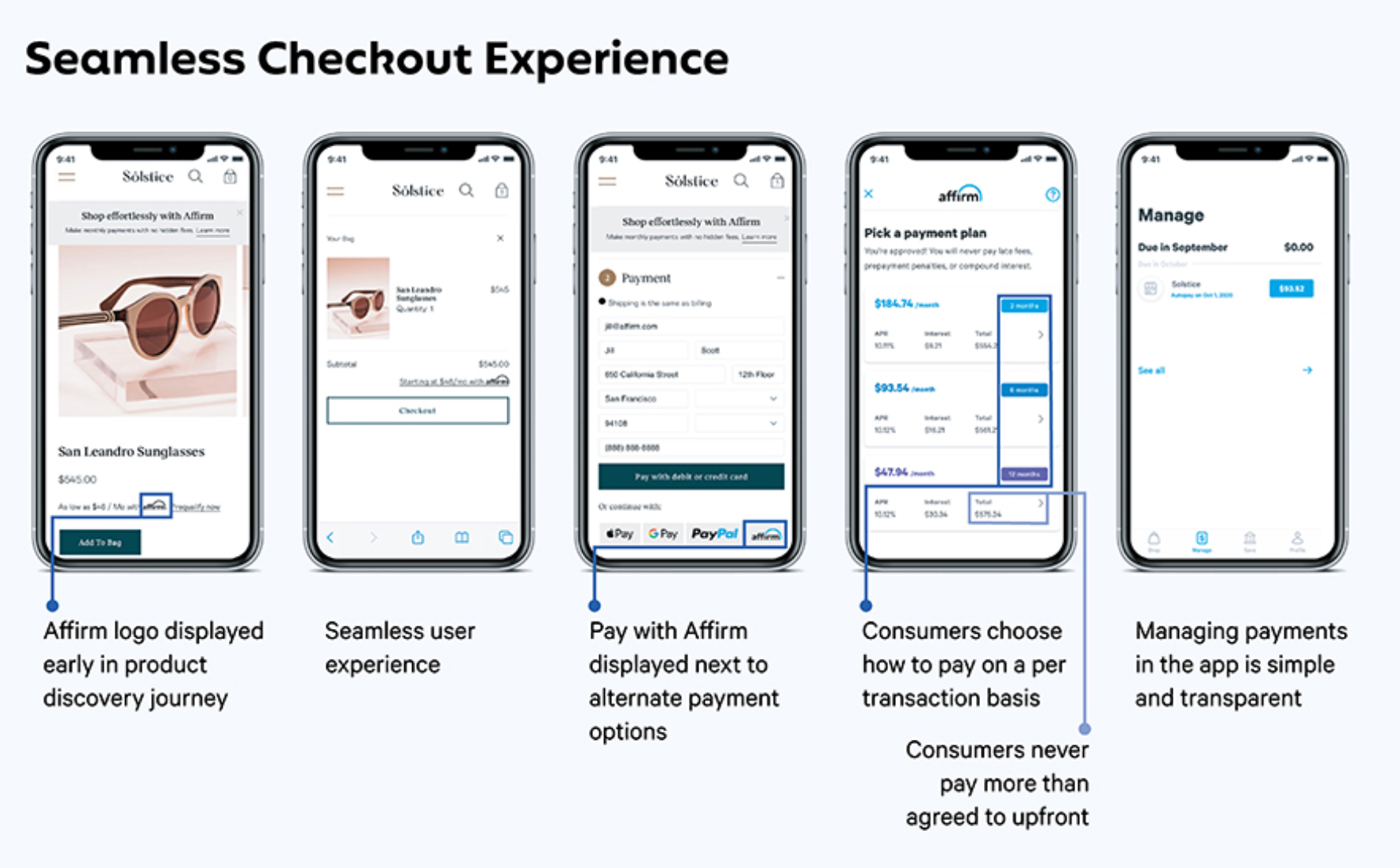

Unlike banks or credit card companies, Affirm establishes partnerships with merchants, to be included as one check out option in the purchasing flow (Figure 1).

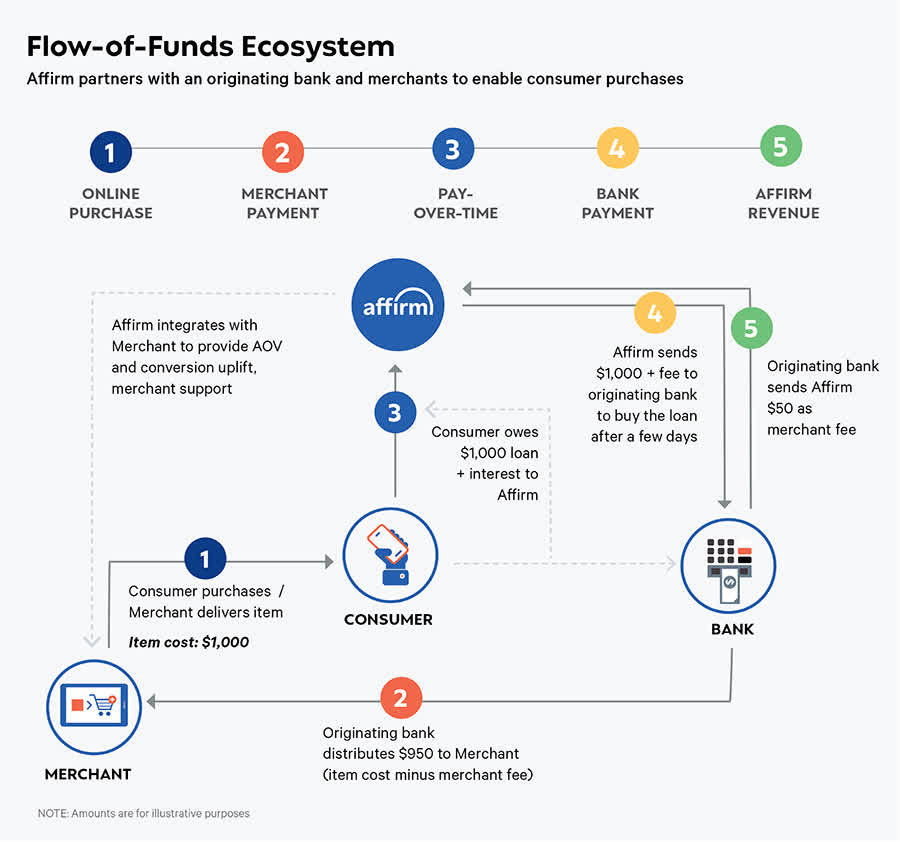

From the purchase event, the funds flow works as follows (see Figure 2 for illustration):

- Consumer purchases, hypothetically, a US $1,000 item. The merchant delivers the item.

- Bank disbursed cash to the merchant. The cash is US $950, the item cost minus fees (hypothetically: US $50).

- Affirm logs that the consumer has a loan for US $1,000 plus fees.

- Affirm sends the bank US $1,000 + fees to buy the loan from the bank.

- Bank sends Affirm US $50 as merchant fee.

From this flow, you can see that Affirm generates revenue from the fee of the original loan (ultimately, the fee is paid by the merchant after it passes through the bank) and the interest rates on the loan from the consumer.

Figure 2 illustrates that Affirm’s business has three stakeholders:

- Merchants. In return for paying Affirm fees to generate loans, merchants get higher check-out conversion and higher average spend (anywhere between 80-90% higher average order value).

- Banks. The banks make money when Affirm buys back the loans (principal plus accrued interest rates).

- Customers. Customers get additional purchasing power and the flexibility of paying back the purchase over a period of time, at variable interest rates (non-compounding), with no late fees.

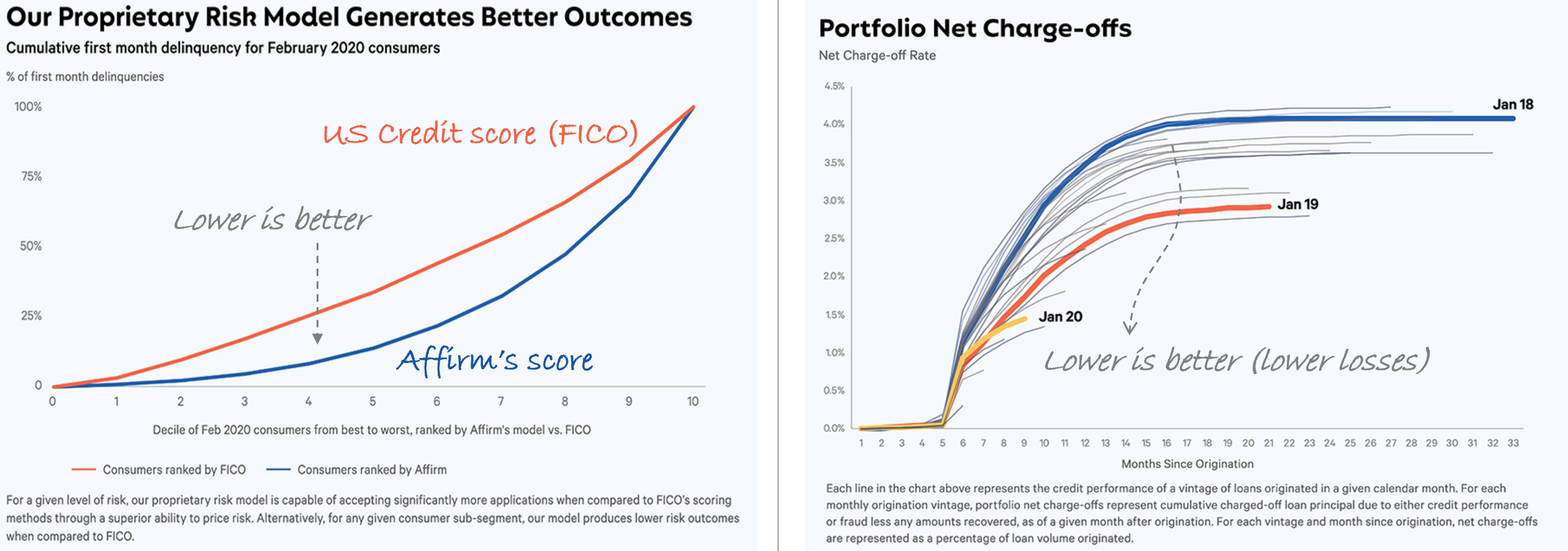

Because Affirm buys the loans back from the bank, the company holds the debt on its balance sheet. Therefore, the company must have a good credit risk profiling system to ensure low default rates of the loans it holds. And Affirm shows that it does (Figure 3). The company boasts a weighted-average quarterly delinquency rate of ~1.1% for the 36 months ended September 30, 2020.

How is Affirm’s business performing?

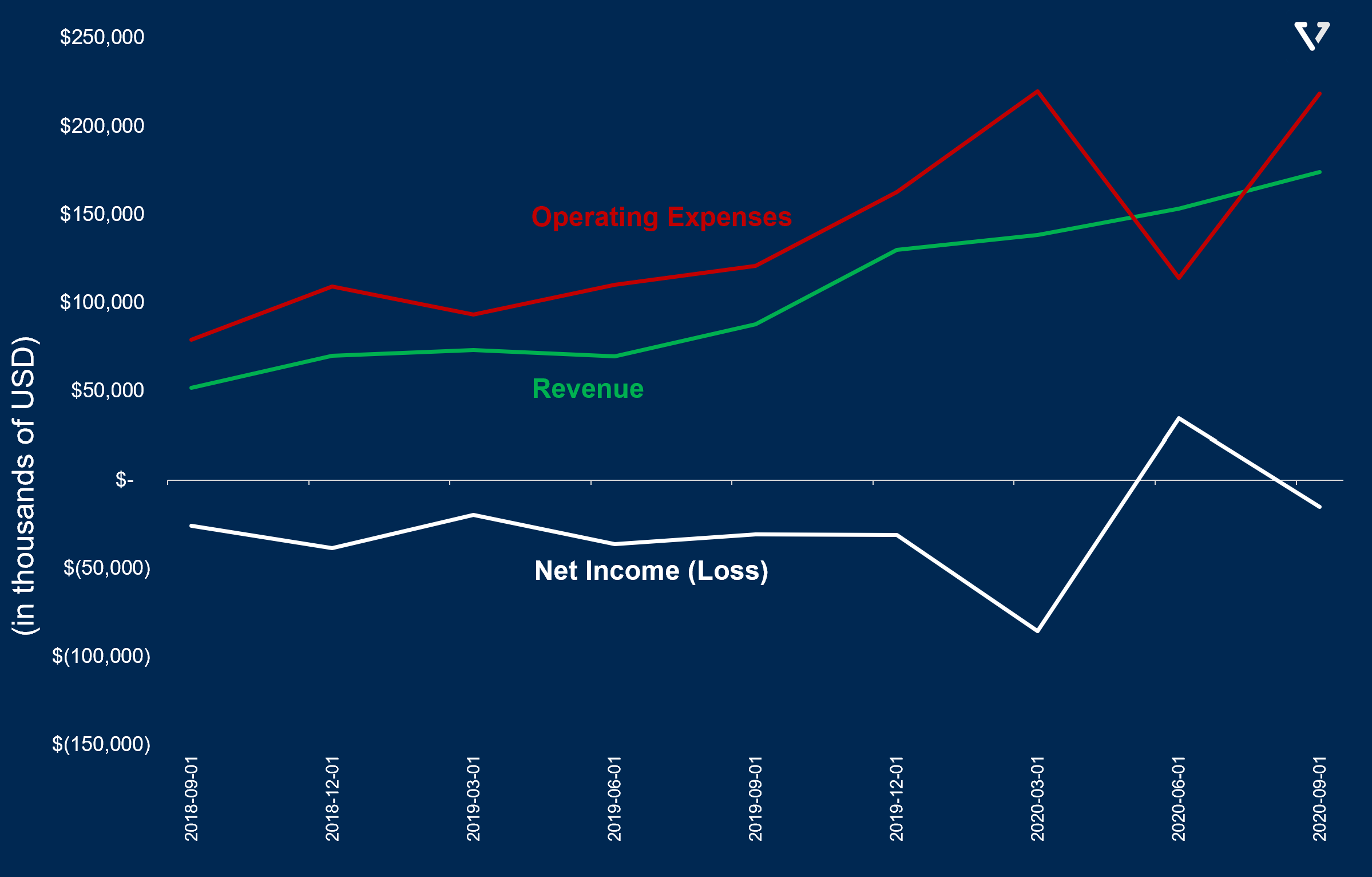

So far, the business is not profitable. In fact, it’s still seeing volatilities in the revenue and operating expense growth (Figure 4). Critically, leading up to Q2 2020, it appeared that expenses growth rate (red line) outpaced revenue increase.

Affirm’s business also has two significant concentration risks:

- Its growth is closely tied to that of Peloton’s. Peloton is one of the beneficiaries of the stay-at-home trend, with its revenue increasing 172% in fiscal Q4 2020. As of September 2020, Peloton contributed to 30% of Affirm’s revenue (more than double from the same period a year ago). If Peloton sales go down, so will Affirm’s.

- The majority of Affirm’s loans is originated from one bank, Cross River Bank (CRB). This partnership is non-exclusive, which means CRB can offer loans to Affirm’s competitors. There’s also a risk of termination of the agreement which will significantly hamper Affirm’s lending business.

All the Roles: Ant Group – the superstore of financial products

Unlike the two companies mentioned above. Ant does everything a bank does, but does not want to be categorized as a bank.

What is Ant?

Established five years after Alibaba‘s emergence, Alipay (which was later renamed Ant Financial and Ant Group) was first created by Jack Ma and associates to facilitate e-commerce transactions on Alibaba’s platform. At the time, one of the primary challenges of mass adoption of e-commerce in China was the lack of trust between the seller and buyers. Alipay was created as an intermediary that would keep the consumer’s money in escrow until delivery was completed, after which the money would be transferred to the seller. In a way, it is what PayPal was to eBay in the early days.

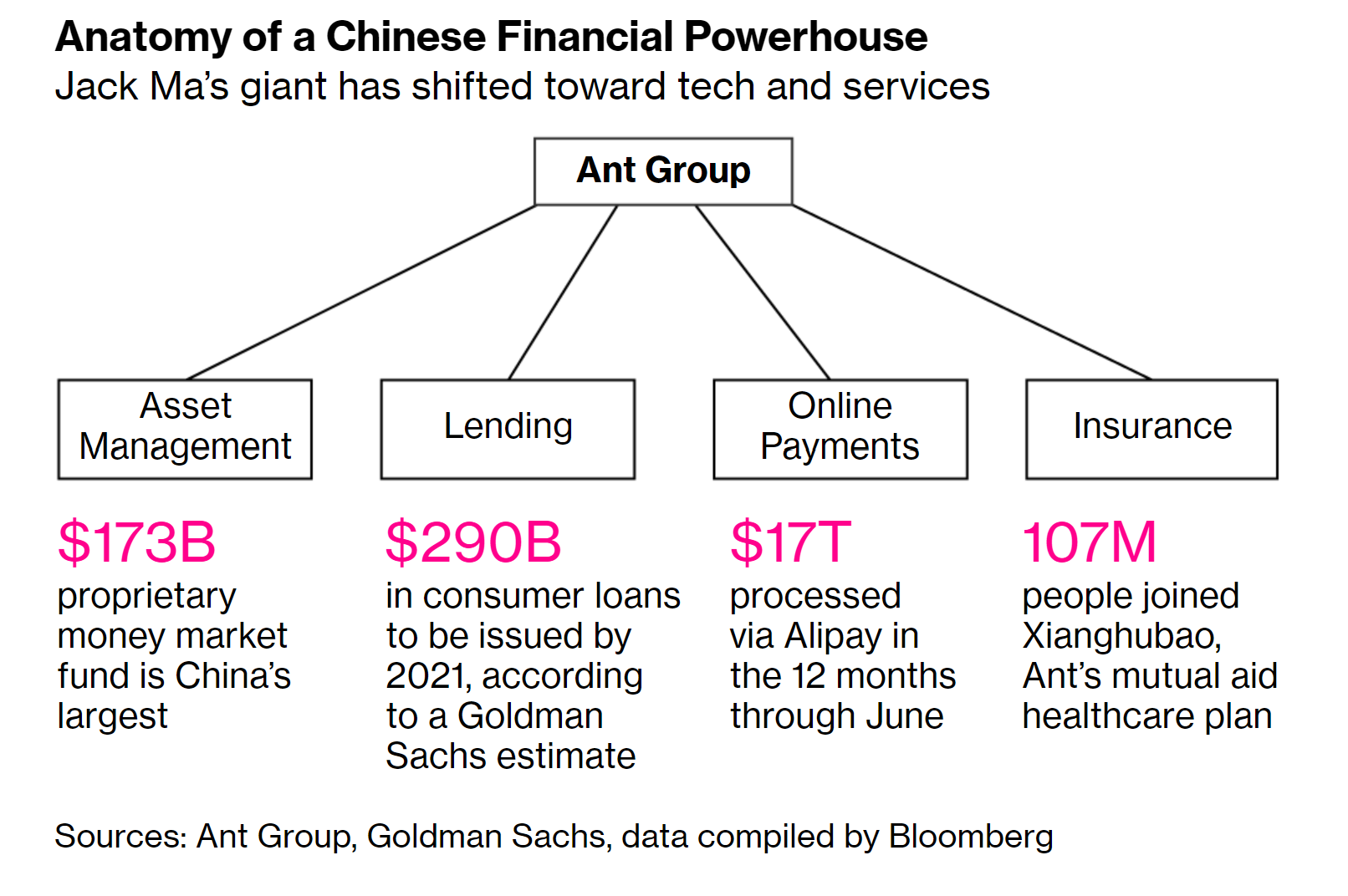

In 2014, Alipay was merged into Ant Group. Today, the company is used by more than a billion users and more than 80 million merchants, processing more than US $17.7 trillion in total transaction volume in the twelve months ending June 2020. In its home market, China, it has 54.4% mobile wallet market share, but it also has a significant user base outside China. It has more than 300 million users via partnerships with local e-wallet providers in South East Asia, India, South Korea, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

The company is very aggressive in cross-selling its products to its users. Ant regularly makes its credit service the default payments (even when the user has not set it as default) and automatically increases the credit limit so that the user borrows more. There’s a really good FT article about this aggressive tactic.

As a result, 80% of its customers use three or more of Ant’s services, and about 40% use all five services.

If the services above sound like services a bank would offer, well, that’s because it does. Yet – Ant is adamant in not being seen, let alone regulated as a bank. This past summer, Ant dropped “Financial Services†from its name. It even goes as far as requesting securities firms to assign technology analysts to cover the company, rather than a bank and financial analysts.

The goals are two-fold:

- Higher valuation. Large cap tech stocks in China have a higher price-to-earnings ratio three times higher than their financial counterparts.

- Less regulations. By being viewed as a technology company, Ant hopes to be less regulated and be less concerned about stringent reserve requirements (when lending out money) and the need to get various licenses.

Don’t Anger the Chinese Government

Ant was supposed to go public in the Hong Kong and Shanghai stock markets, rather than in New York. This would have helped bolster the international standing of these two exchanges as rivalry between China and the US was heating up.

The IPO was highly anticipated. It was supposed to raise about US $30 billion from public investors. The anticipation created a frenzy. Retail investors in both Hong Kong and China, from students, taxi drivers to working professionals, used up their savings and borrowed heavily to invest in the IPO and used leverage that can oftentimes be more than 10x.

But alas, it was not meant to be.

- Days before the IPO, on October 24th 2020, Jack attended a financial forum in Shanghai and gave a 21 minute speech that criticised the regulating bodies for being overly-focused on risk and overlooking the credit needs for development. He also called large Chinese banks to have “pawnshop mentality†and called out the lack of financial systems in China: “There’s no systemic financial risks in China because there’s no financial system in China. The risks are a lack of systems.â€

- The comments went viral. President Xi Jinping himself made the call to stop Ant’s IPO. On October 31st, financial regulators drafted new regulations directed at Ant.

- On November 2nd 2020, Jack Ma was summoned to meet the regulators. On the same day, the draft of the new regulations was published.

- On November 3rd 2020, the IPO was halted on both exchanges.

What happens next?

With the new regulations, Ant will have to reorganize its business. The new rule mandates that Ant provides at least 30% of the loans it makes to its users, in contrast to its current practice where only 2% of the funds it lends out is still on its balance sheet. This capital requirement will significantly slow down Ant’s lending growth (which is the primary way it makes money. In 2020, 40% of its revenue came from lending) and will make the business a lot more capital intensive and volatile.

When Ant decides to go public again, which may happen in late 2021 or 2022, then it will be seen (and regulated) more as a bank. This means a much more modest valuation (Chinese banks typically trade an average 4 – 10x their earnings, while tech companies regularly trade between 30 – 50x their earnings) and increased/heavier scrutiny.

[mc4wp_form id=”1064″]