In this week’s article, we discuss DiDi Chuxing’s (the Uber of China) upcoming IPO.

Risks in investing in China-based companies

Before you proceed – there are several risks that you need to know regarding investing in companies based out of China:

- The US and China relationship continues to degrade. As a result, more and more Chinese technology companies are forced to delist from the US stock exchanges.

- The risk of fraud is higher. Chinese companies listed in the US are not subject to the same accounting audit standards that US companies have to abide by. There have been several high profile frauds in the past few years.

- Because of this, last year, the US introduced a bill to delist all Chinese companies that do not abide by accounting audits standards and cannot prove that they are not under foreign government control. This bill has been signed into law in December, and the SEC has started enforcement of the law.

- Regulatory pressure also comes from the Chinese government. Beginning with the scuttled IPO of Ant Financials last year, Beijing has expanded its clamp down to other homegrown tech companies.

Alright, with that out of the way, let’s talk about DiDi Chuxing – the Uber of China.

DiDi Chuxing – the Uber of China

Cheng Wei, a former Deputy General Manager of Alipay, founded Beijing Orange Technology Co. and launched DiDi Dache (which means “Beep Beep Call a Taxiâ€) in 2012. At the time, the company was a software service that connected taxi drivers with passengers. The service then evolved into a ride-hailing service after Cheng met with Garret Camp (co-founder of Uber), who at the time was visiting China, as Uber was looking to expand there.

Over the years, DiDi fought highly competitive battles on multiple fronts. It competed against Uber and Kuadi Dache (another local player). The battle was waged over multiple years, burning hundreds of millions of dollars to gain market share. On the urging of their investors, DiDi merged with Kuaidi to form DiDi Chuxing in 2015.

The battle with Uber raged on for another year. In 2016, Uber decided to exit China and sold its Chinese operations to DiDi Chuxing for a significant stake in the company (as of the IPO, Uber still owns 12.8% of DiDi). This final consolidation made DiDi the largest mobility app in China, with more than 90% market share (sorry – source is in Chinese).

Currently, DiDi operates in 4,000 cities in 15 international markets – although more than 90% of its revenue is still derived from China.

Anatomy of DiDi’s services

In our deep dive into Grab, we discussed the key ingredient that is necessary to start a super app. In short:

Super apps typically start off by providing a core function that meet two criteria:

- A function that is used often (multiple times per day), enabling the app to gain mindshare/habitual use.

- A function that has embedded network effects, allowing the app to grow its user base rapidly.

Ride-sharing definitely meets these two criteria. In South East Asia, Grab started as a ride-sharing app and branched into other functions (payments, insurance, online shopping, etc). In contrast, DiDi has not reached the same level of diverse functionalities that a typical super app offers. This is because China’s market is already saturated with two other super apps (Tencent and Alibaba).

So, instead of trying to be the super app that helps you navigate through everything, DiDi is more focused on being the super app for the mobility vertical (well – ok, the company does have DiDi Finance, but it’s still in a very early stage). See Figure 1 for the services DiDi offers – there’s a skew for different transportation modes and for different price ranges.

Of the above services, the company reports three business segments:

- China Mobility: Ride hailing, taxi hailing, chauffeur, and hitch.

- International: Ride hailing, and food delivery.

- Other Initiatives: Bike sharing, certain auto solutions, intra-city freight, community group buying, autonomous driving, financial services.

The COVID impact

As you would expect for a mobility service company – global lockdown was really bad for business.

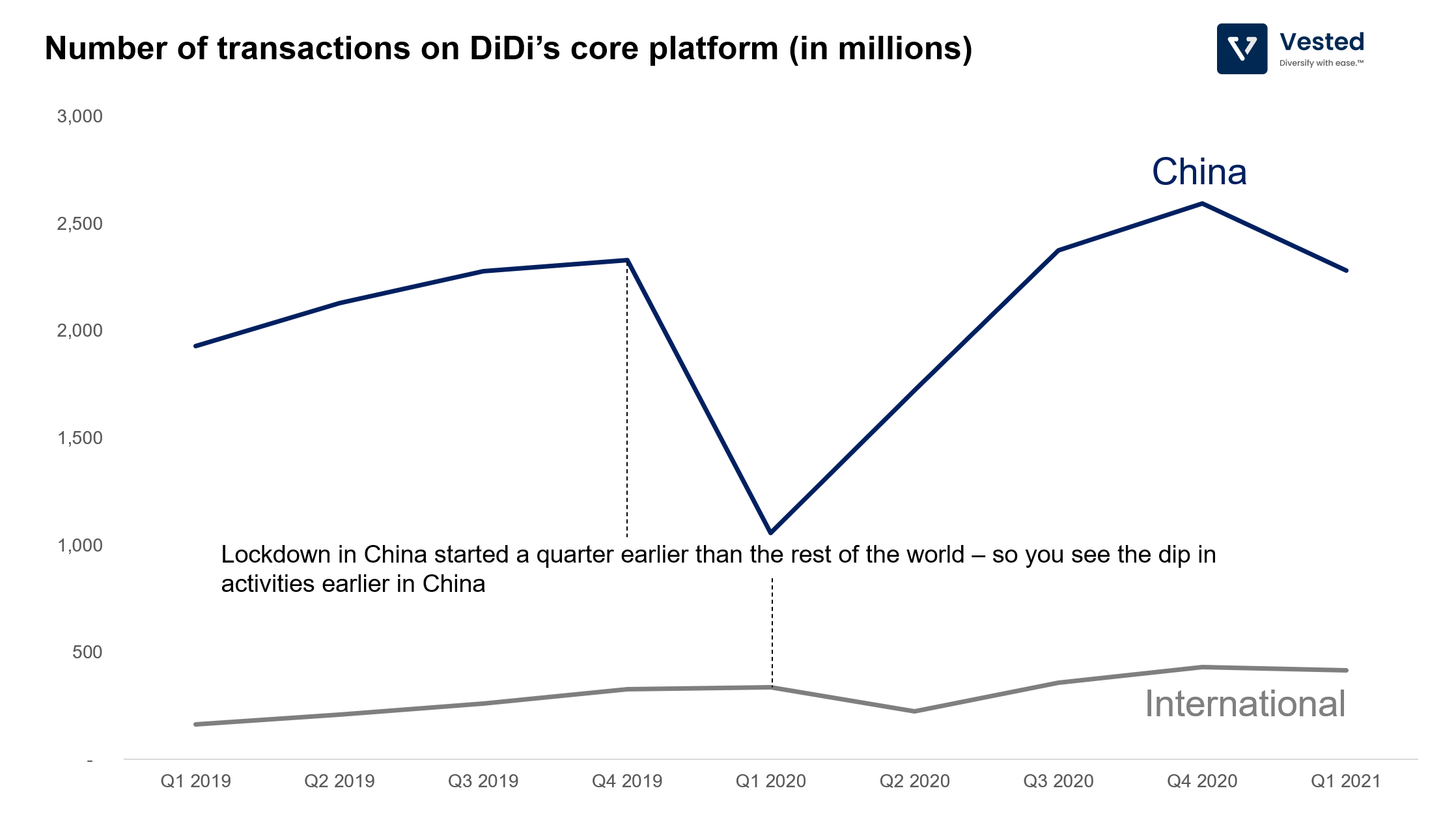

Two key takeaways from Figure 2:

- The number of transactions in China went down 55% between Q4 2019 to Q1 2020. Lockdown in China started a quarter earlier than the rest of the world – you see that in the chart above.

- DiDi experiences seasonality in its business. Q1 is typically slower for the company, because of the Chinese New Year holiday.

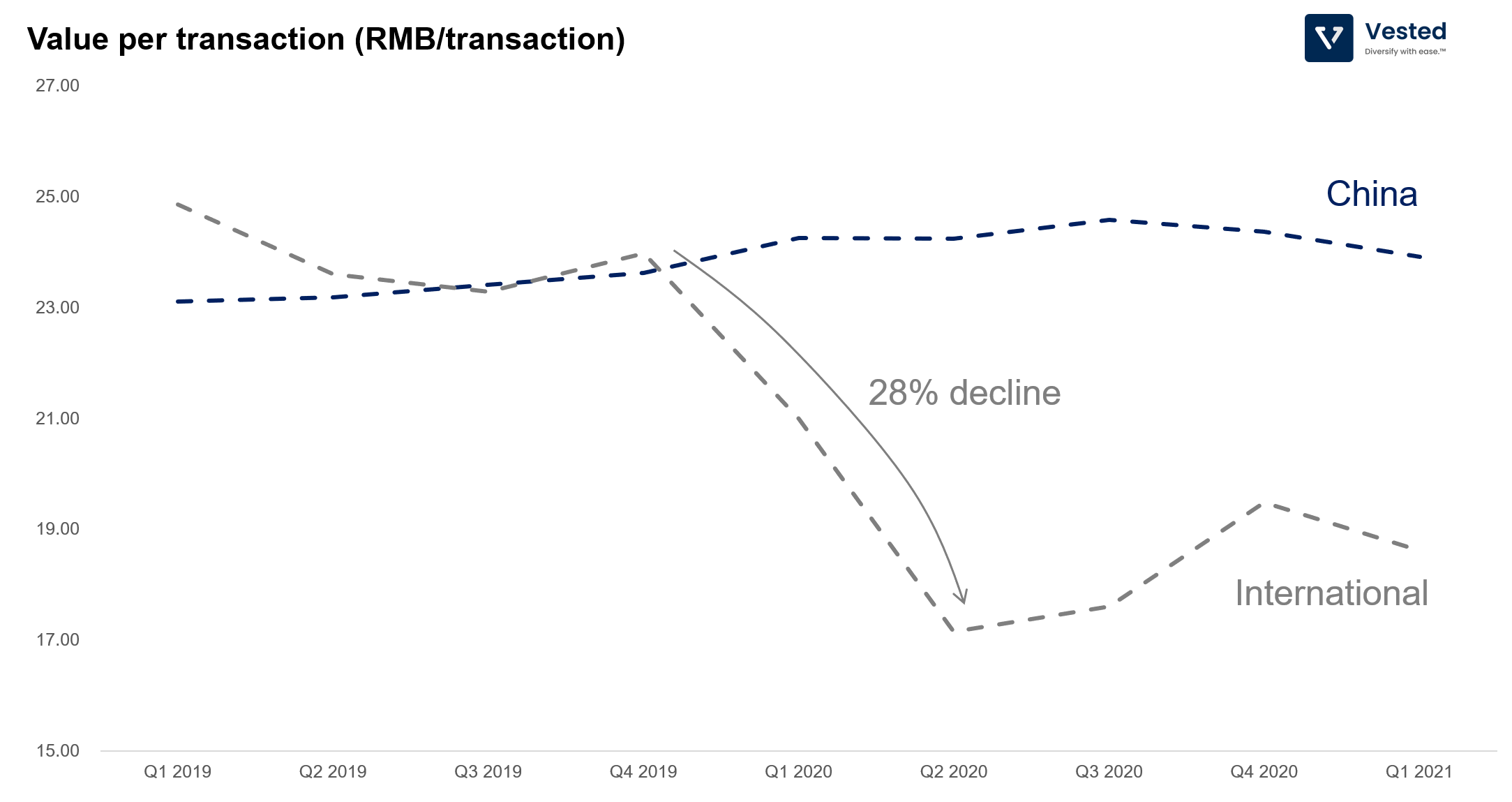

Generally, when evaluating ride-sharing/food delivery companies, we need to look deeper than top line revenue growth to really understand the growth rate of the company. Ride-share companies can juice top line growth by increasing incentives (for both riders and drivers). While this hurts profitability, it can increase growth in the short term. But the growth may not stick in the long run – especially when the switching cost to another ride-share/delivery app is very easy to do (this is called multihoming).

So instead of just looking at total revenue or gross transaction volume (GTV), we look at the average value per transaction (in RMB) for DiDi. See Figure 3.

Note: We calculate this average value per transaction by dividing the GTV (which is the total transaction value including taxes, customer/driver incentives, tolls and other fees).

Average value per transaction = GTV / number of transactions on the core platform

Here are two key takeaways from Figure 3:

- Despite the decline in the number of transactions (due to the lockdown), the average value per transaction in China remains relatively flat. Note: RMB 23 is about US$3.6 at the current exchange rate.

- Interestingly, the average value per transaction in the international market has declined and has not recovered. Between Q4 2019 to Q2 2020, the average value per transaction went down by 28%. Since the decline started in Q1 2020, this means this is not due to the global lockdown in international markets – the decline precedes the lockdown. DiDi did not explain the reason for this trend.

Consistency in inconsistency

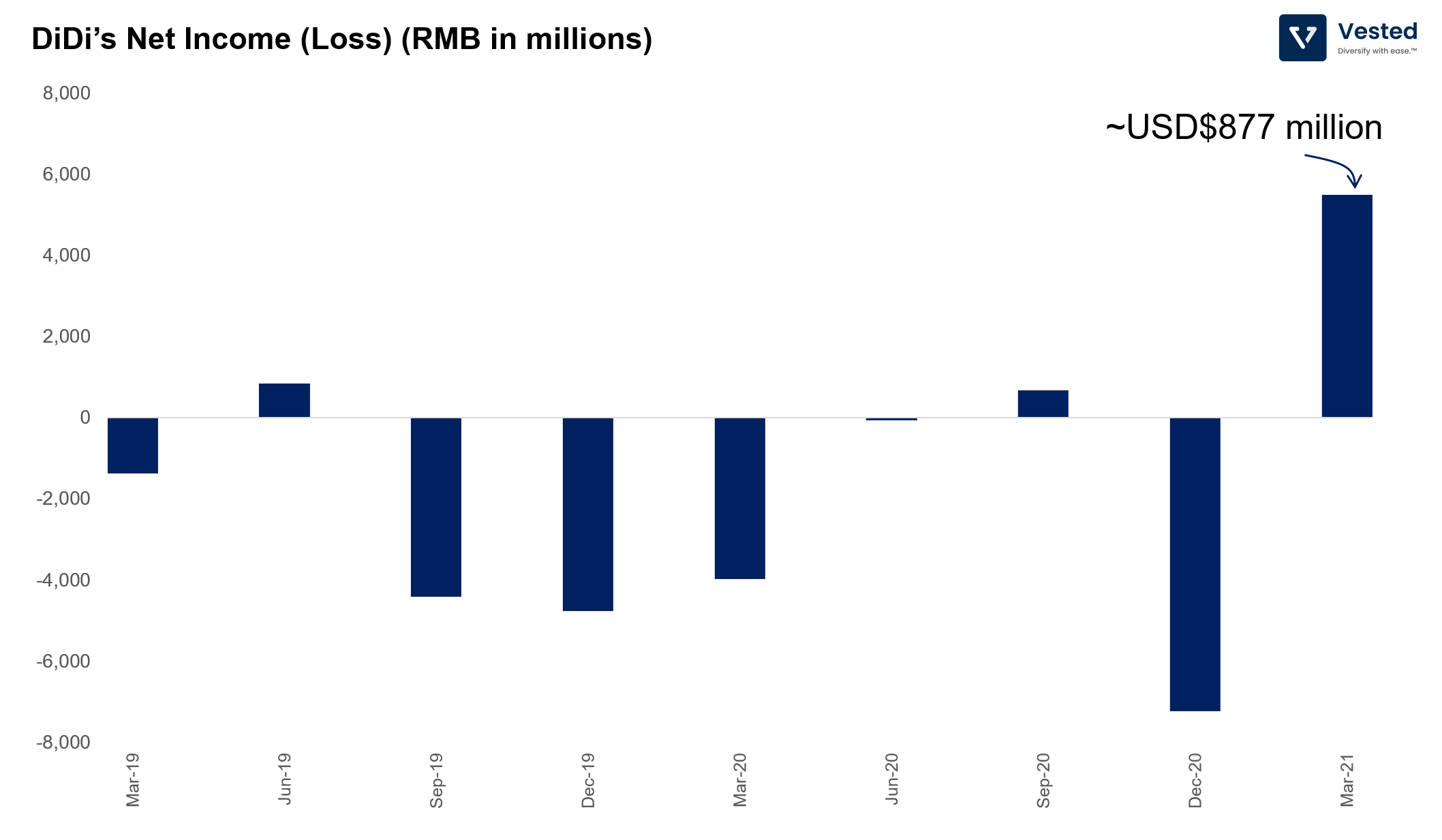

DiDi’s business is not profitable. There are wild swings in losses from the seasonality of the business and from the need to drive incentives and other marketing expenses. Over the past nine quarters, the company only enjoyed three quarters of positive net income, and for these three quarters, profits came from non-recurring selling of investments. The profits from Q1 2021 came from selling Chengxin Technology Inc., DiDi’s version of group buying businesses. This means that it’s unlikely that the company can maintain profitability.

Ok – so you may overlook the fact that the company is not profitable, since there is no such thing as a profitable ride-sharing company (neither Uber, Lyft, nor Grab are profitable).

But is there room in the public market for another money-losing ride-sharing company with unpredictable swings in losses? And what is the path towards profitability?

In its prospectus, DiDi stated that there are three key areas of investments for proceeds from the IPO. None of these reasons seem to provide paths towards better unit economics or better profitability:

- 30% of the cash to be raised will be for international expansion. International expansion typically means costly battles with existing providers to acquire customers and drivers. International expansion also creates an odd competitive dynamic. In Latin America, DiDi competes with Uber. But at the same time, Uber owns 12.8% of DiDi…

- Another 30% for further investments in electric vehicles (EV) and autonomous driving (AV) technologies. These two areas are becoming increasingly crowded. On the EV front, DiDi will compete with other Chinese EV car makers. And, on the AV front, DiDi’s chief competitor will be Baidu, who is developing its own robo-taxi service (note: Baidu is the Google of China).

- And about 20% to introduce “new products and expand existing offerings for the benefit of our consumersâ€. This could be new products that increase engagement on the DiDi platform such as financial services.

Valuation

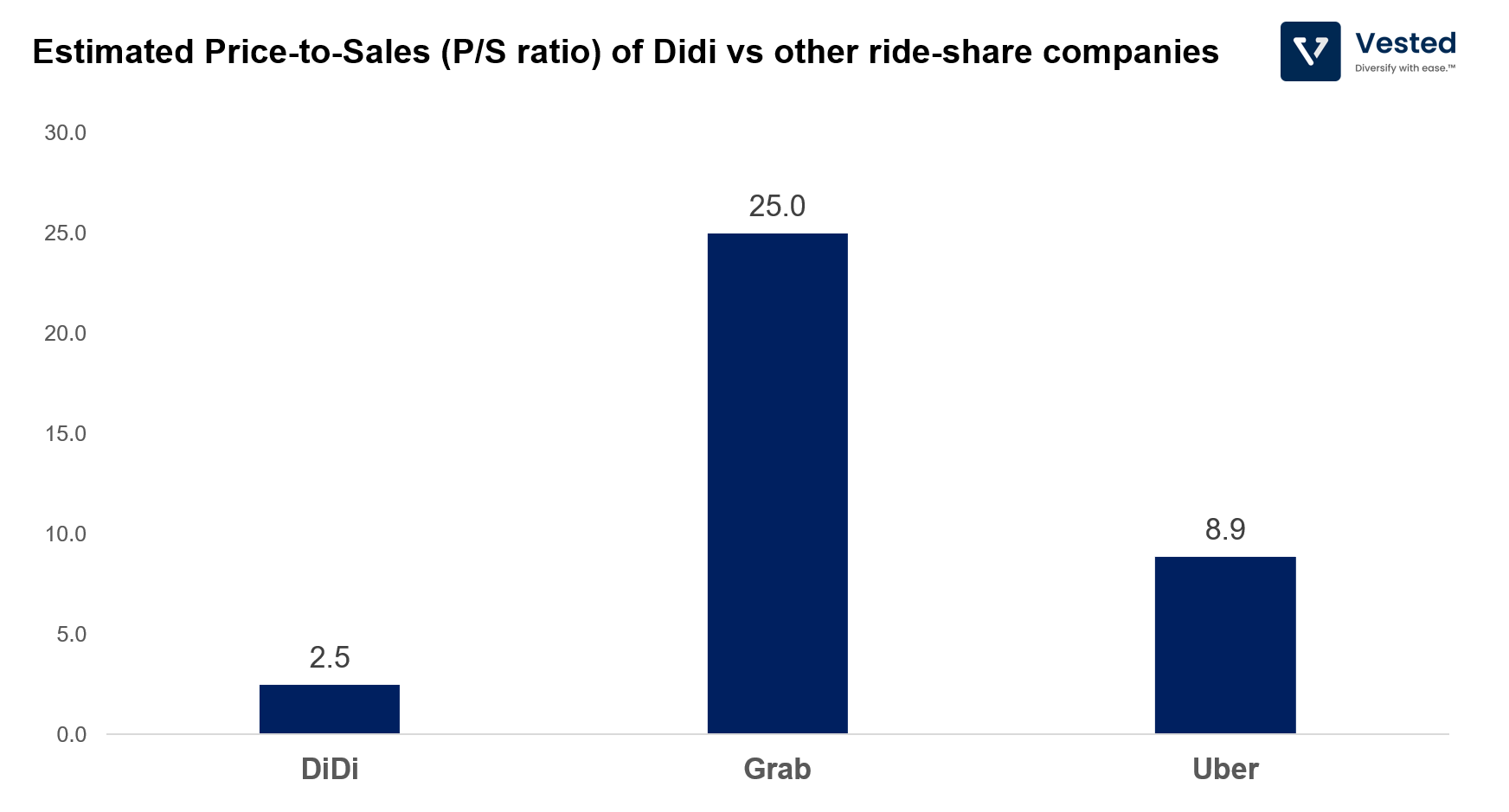

It’s difficult to assess the valuation of DiDi and compare that with that of Grab and Uber. For one, it’s unclear what final valuation DiDi will have. According to WSJ, it might be around US$70 billion. Contrast that to that of Grab, which is valued around US$40 billion. Meanwhile, Uber is valued at US$93 billion. From these numbers, we can estimate the price-to-sales ratio of the three companies (as a metric of valuation). See Figure 5.

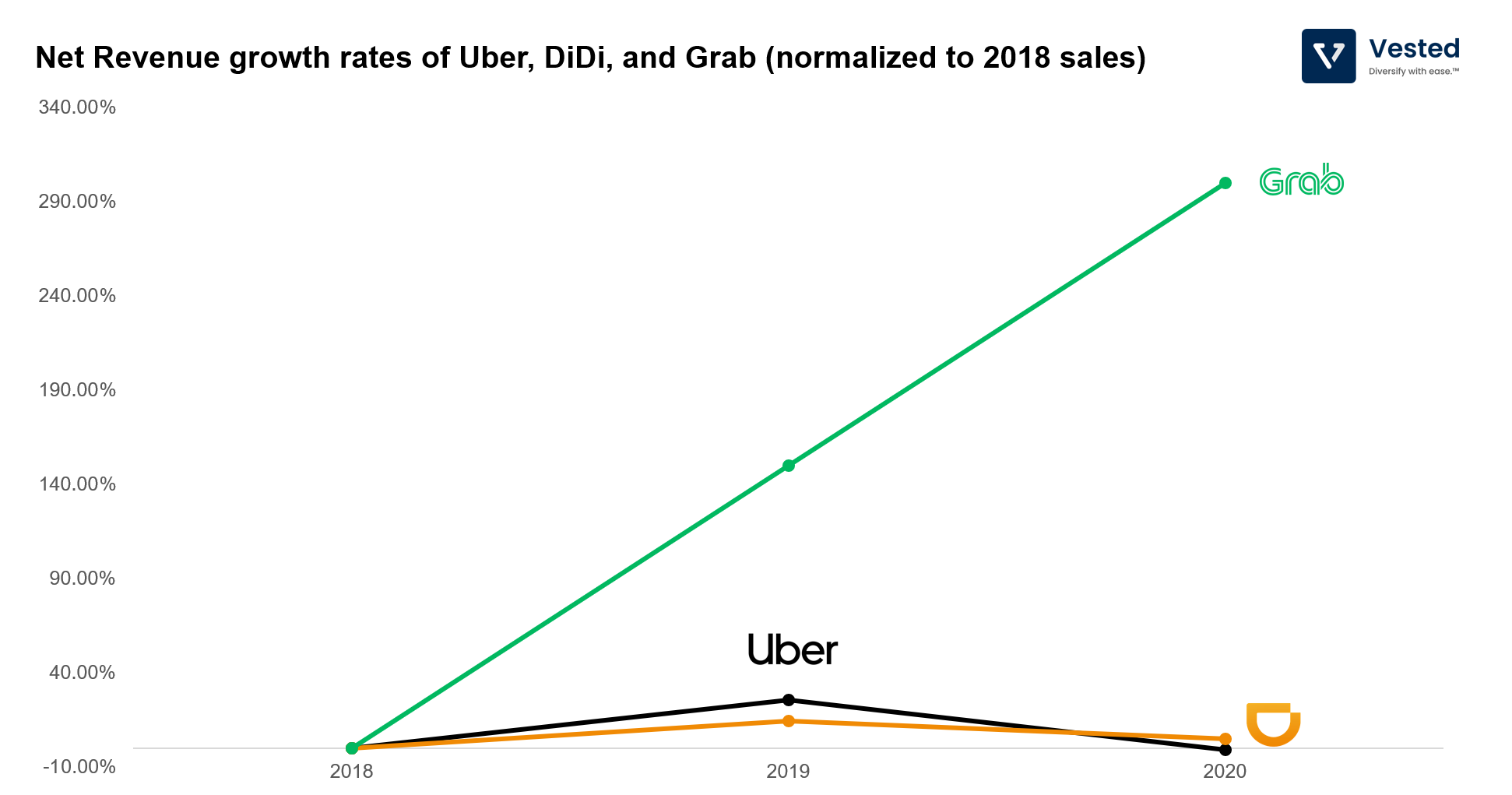

It’s clear that Grab has the highest valuation, while DiDi has the lowest. Why is that? Is it because investors are looking for the growth narrative? Possibly.

In terms of revenue, Grab is the smallest (2020 revenue is at US$1.6 billion; That’s 13.5x smaller than that of DiDi’s). But compared to DiDi, Grab is growing at a much faster rate (Figure 6). Yes – DiDi has the dominant market share in China, but it is still looking for its next growth engine. Meanwhile, Grab has been able to propel its revenue growth by increasing spend on its platform through different services on its super app.

As for Uber? It represents optionality in the two other companies, since Uber still owns 12.8% of DiDi and 16.6% of Grab.