Dollar-cost averaging (DCA) is an investment method where a fixed amount is allocated at regular intervals into a financial instrument, regardless of its market price at the time. The DCA strategy may help reduce the impact of short-term price fluctuations on an investor’s portfolio.

In this article, we discuss why you may want to consider dollar-cost averaging, and how the Vested app can help.

Why should you consider dollar cost averaging?

Automatic recurring investments can be beneficial in two ways:

- Reduce volatility of returns

- Remove the mental burden of deploying capital

Reducing volatility of returns

The DCA investment method may offer two practical benefits:

There are multiple points of view on the benefits of dollar-cost averaging. Some say it’s worse for returns, others say it’s better. As is with most things in life, the true answer is it depends.

Dollar-cost averaging is better for returns when the market is declining and is worse when the market is up. Imagine two hypothetical investment scenarios that consist of 5 investing periods.

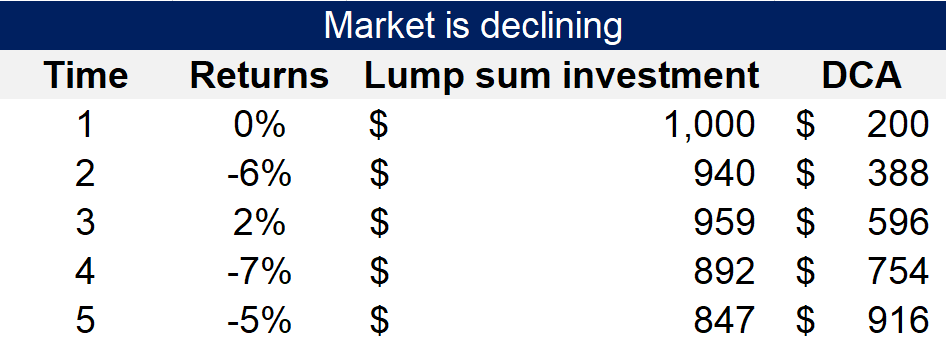

When the market is in a decline

In Table 1, we present a simplified investing scenario where the market is in decline. In this scenario, you can either invest $1,000 up front in a lump sum, or dollar cost average (DCA) into the market at a pace of $200 per investing period. At the end of five periods, the DCA approach comes out on top, yielding $916 (vs. $847 had you deployed the investment as a lump sum).

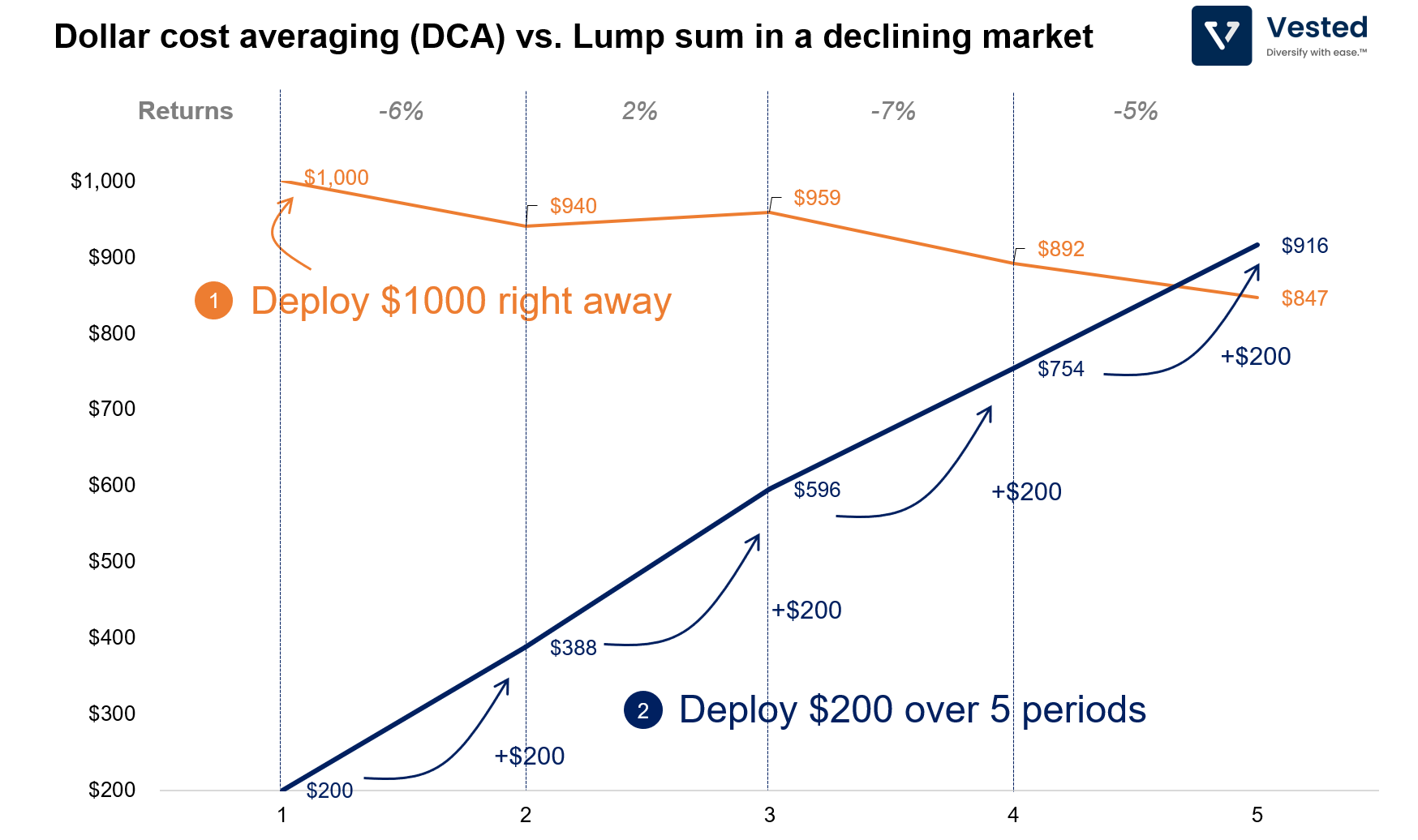

See Figure 1 for an illustration. The orange line (for lump sum investment) ends up being lower than the dark blue line (for DCA).

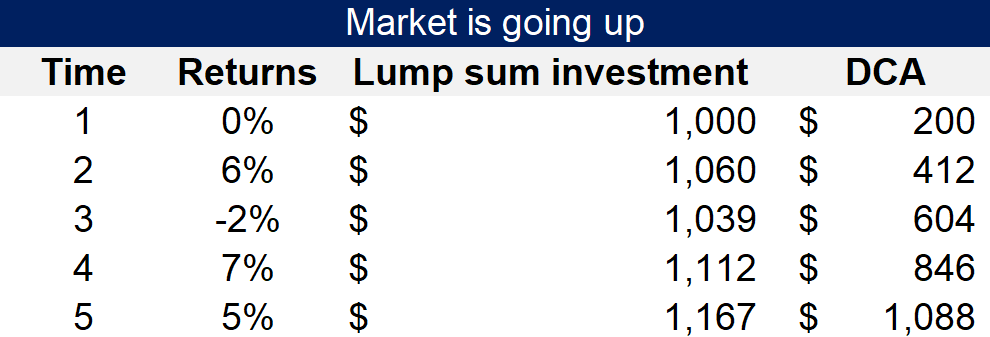

When the market is going up

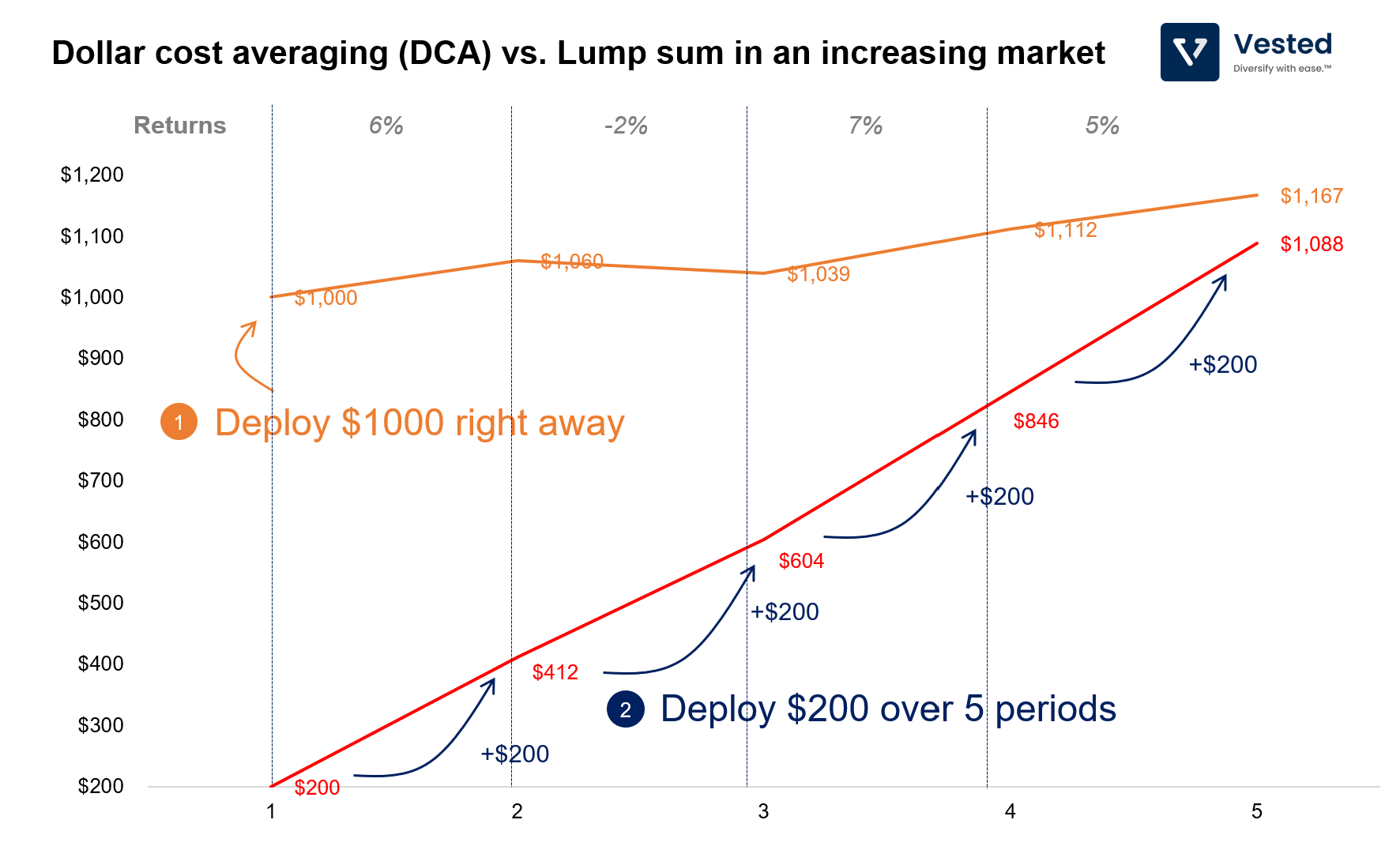

You can do the same exercise for when the market is going up. In Table 2, we present a simplified investing scenario where the market is going up. Similar to before, you can either invest $1,000 up front in a lump sum, or dollar cost average (DCA) into the market at a pace of $200 per investing period. At the end of five periods, the DCA approach comes out below, yielding only $1,088 (vs. $1,167 had you deployed the investment as a lump sum).

See Figure 2 for an illustration. The orange line (for lump sum investment) ends up being above the red line (the DCA approach). Note, however, that this simplified approach does not take into account the negative impact of inflation on the cash holding, which would further reduce the real returns of the DCA approach.

Do you now see why both opinions are true? The lump sum approach is better if the market is going up, but DCA is better when the market is down. The problem is, it’s hard to know how the market will behave in the future. You can try to time the market, but that, more often than not, leads to subpar returns.

To extend beyond the simplified examples above, you can run simulations to see if the above observations hold. Investing is path-dependent – the outcome varies depending on when you start, and how often you invest. In their paper, Kirby et al, ran a simulation of one million possible investing pathways, comparing the outcomes for the lump sum approach vs. the dollar cost averaging (DCA) approach. The result is shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Distribution of outcomes of a million simulated investing paths, comparing DCA (orange) vs. lump sum (blue) (Source)

Figure 3 above summarizes the trade-offs between the two approaches. Notice that the orange bars (the DCA probability outcome) is narrower/tighter than the blue bars (the lump sum probability outcome). This is because the DCA approach gives the investor the benefit of time diversification, producing a more predictable outcome, at the expense of possibly lower returns. In contrast, the lump sum approach gives a wider distribution of outcome; depending on when you start, you can either outperform or underperform the DCA approach.

Removing the mental burden of deploying capital

The old saying of buying low and selling high is easier said than done. Most people are afraid to buy low in fear of catching a falling knife (loss aversion). This concern often becomes more pronounced when taking a long-term approach. A long-term investment with DCA may help address this by encouraging systematic allocation over time. By enabling automatic programmatic dollar-cost averaging (DCA), we can remove the mental burden and remove emotion from the capital deployment process. This regular investment strategy may help investors avoid the challenge of deploying the entire investment amount during periods of market uncertainty or elevated valuations.

Which Financial Instruments Can You Invest in using the DCA strategy?

While there are no specific assets defined for dollar-cost averaging, this strategy is generally applied to financial instruments that tend to exhibit price volatility.

The primary objective of dollar-cost averaging in volatile markets is to reduce the effect of short-term price fluctuations by investing a fixed amount at consistent intervals, regardless of the asset’s current value.

Dollar-cost averaging can be applied across various financial instruments. Examples include:

- Mutual Funds: Dollar-cost averaging for mutual funds is often used as the NAV (net asset value) reflects the performance of underlying assets, which may vary with market fluctuations.

- Equities: Dollar-cost averaging strategy for stocks may be considered in cases where equity prices are subject to frequent market movements. This approach may help distribute exposure over time.

- Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs): ETFs are commonly included in dollar-cost averaging investing strategies, as they reflect broader market movements and offer diversified exposure.

How does Recurring Investments at Vested work?

- Pick the investment you want to invest in on a recurring basis (either a stock, ETF, or Vest)

- Set up the buy order (order size, start date, and recurring frequency)

Once you’ve set up the recurring investment, you can always manage them in the Profile section. The recurring investments can be canceled at any time.