A question we have been pondering lately is: how will the oil and gas industry end? We cannot help but ponder this question because long term demand for fossil fuel energy seems to be shrinking:

- EV adoption is accelerating

- Solar panels are getting cheaper (at a faster rate than the most optimistic estimate)

- Battery cost has decreased by 89% from 2010 to 2021

- Renewable energy’s contribution to the global grid is increasing (China alone will add 140 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity, more than the rest of the world combined in 2020. It is also planning on building 150 new nuclear reactors, more than the rest of the world has built in the past 35 years.)

To make matters worse, the industry is in a political crosshair, especially with energy cost fueling much of the global inflation. Two of the industry’s largest companies, Shell and Exxon, recognized in the 1980s that its products contributed to the warming of the planet, which would lead to global catastrophes and political instabilities. Decades later, they were proven right.

To mitigate the reputational damage, in recent years, Shell and other oil companies have taken a more public stance in recognizing the impact of fossil fuels towards climate change. Despite this, behind closed doors, they also participated in lobbying efforts that oppose climate policy and promote climate skepticism.

As you can see, it is really difficult to love these companies…

But will we quit the oil and gas industry? Will oil ever go to zero?

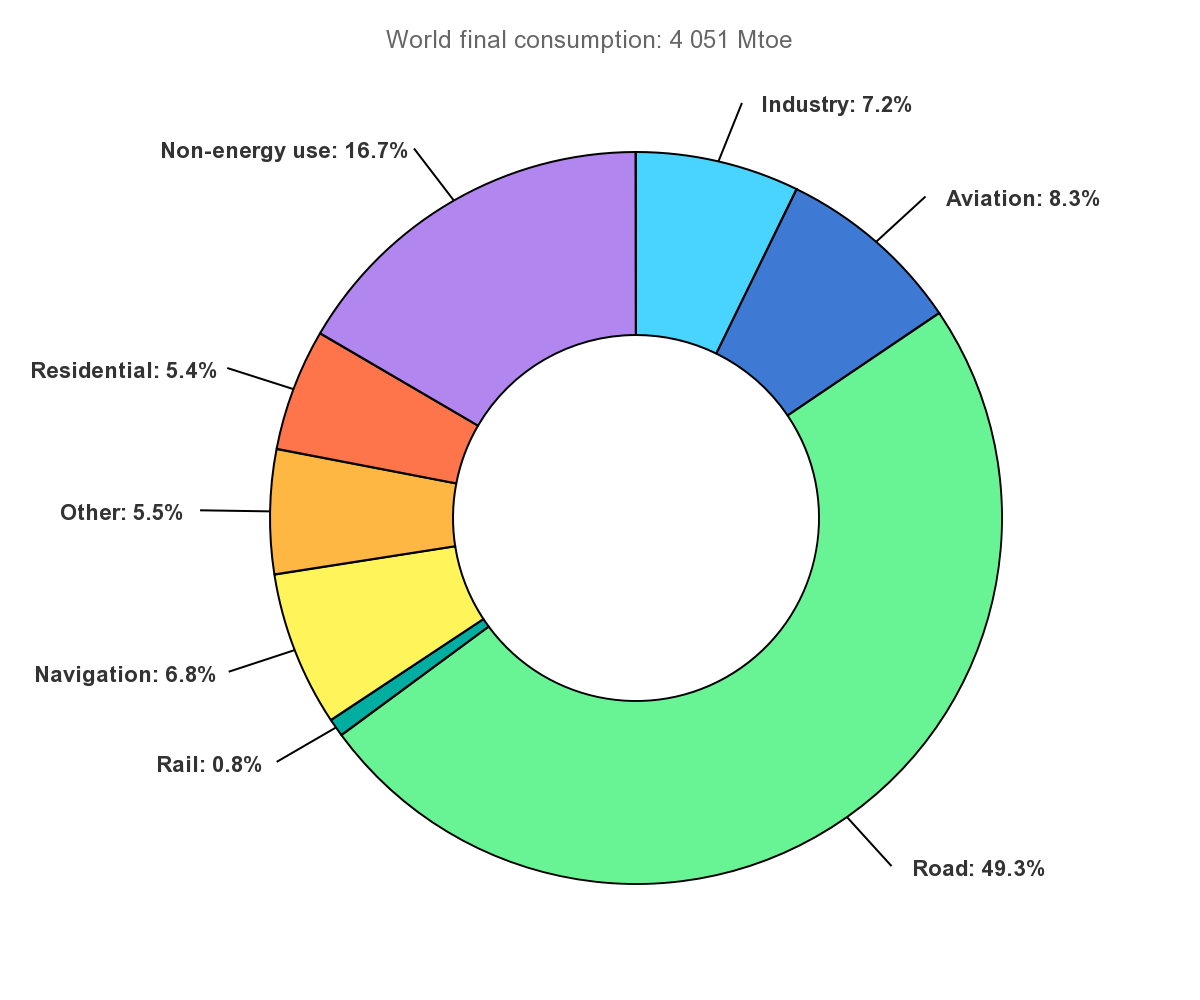

To answer this question, we first have to understand the nature of demand for oil and gas. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of oil consumption by sector. Globally, transportation use drives about half of the world’s oil consumption (the green slice of the pie labeled ‘Road’). In the US, the share of transportation use is a bit higher, at about 67%.

As you can see, the biggest contributor of oil consumption is the transportation sector. But even with the advent of EVs, it will take decades to completely eliminate this consumption. The glide path to a complete replacement of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles to EVs is projected to take decades. Bloomberg projects that there will still be 900 million ICE vehicles on the road in 2040 – more than half the existing fleet. Oil consumption from transportation will decline, but will not reach zero.

Outside transportation, demand for plastics (which are made of oil) is supposed to surge and help drive growth of consumption. Petrochemicals account for ~14% of oil use, and in the past decade large producers have invested more than $200 billion in plastic and chemical projects in the US. Some argue that this investment won’t pan out. Plastics are a much smaller revenue contributor and face concerted legislative efforts to curb its use.

Where does that leave the oil industry? Long term, the sector is despised, with middling demand growth. While in the short term, demand is expected to increase, outpacing supply. What does that mean?

A newfound fiscal discipline

Imagine yourself as an oil executive. Your industry is out of favor. Two years ago, your product prices went negative. Activist investors are pressuring your peers to set bolder emission reduction standards. Some call your sector ‘uninvestable’. And the long term growth of the industry is likely off the table. What do you do?

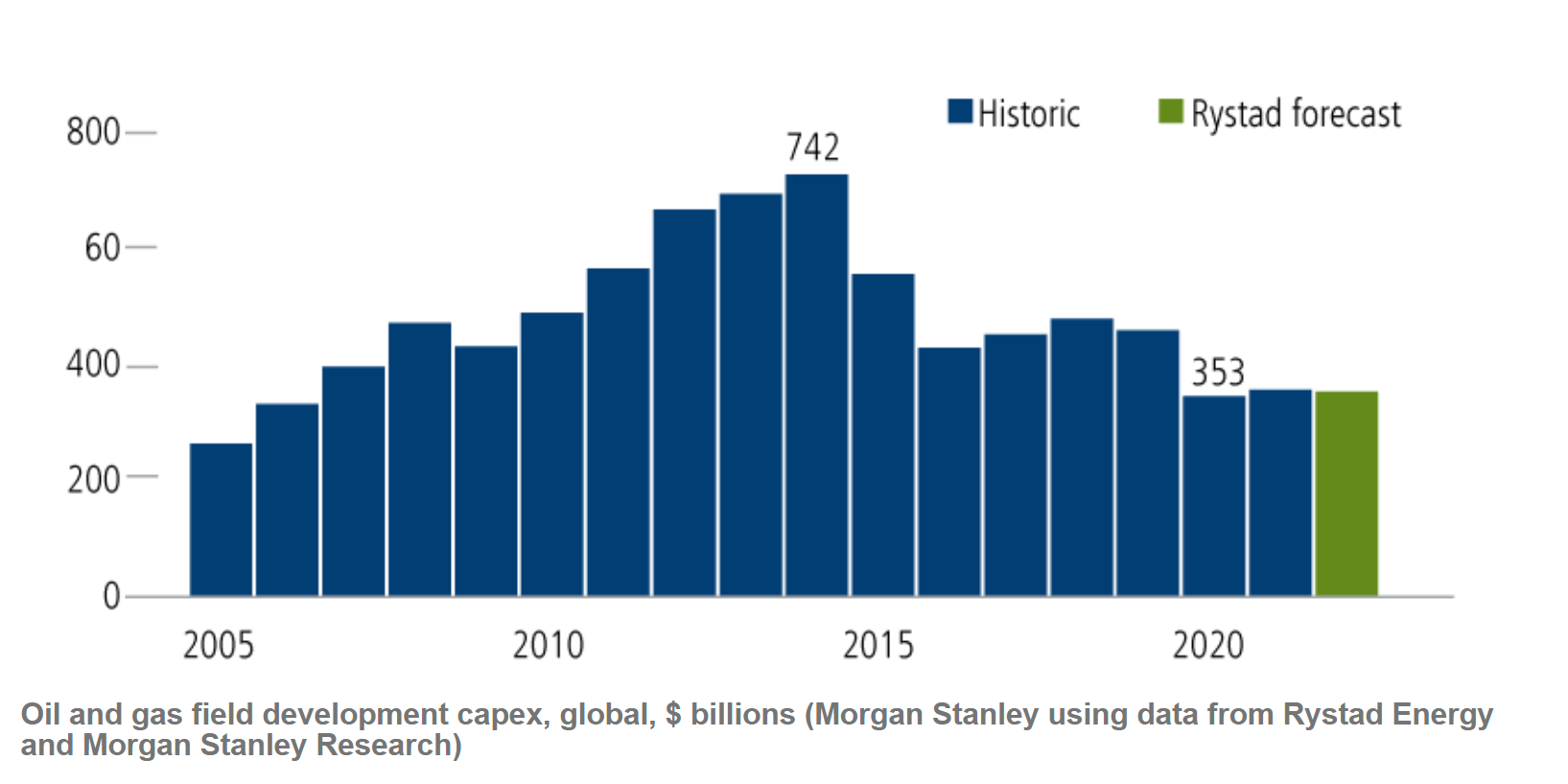

Stop investing in increasing future supply. Capital expenditures of producers went down in 2020, the year the world went into lockdown, and have not recovered since.

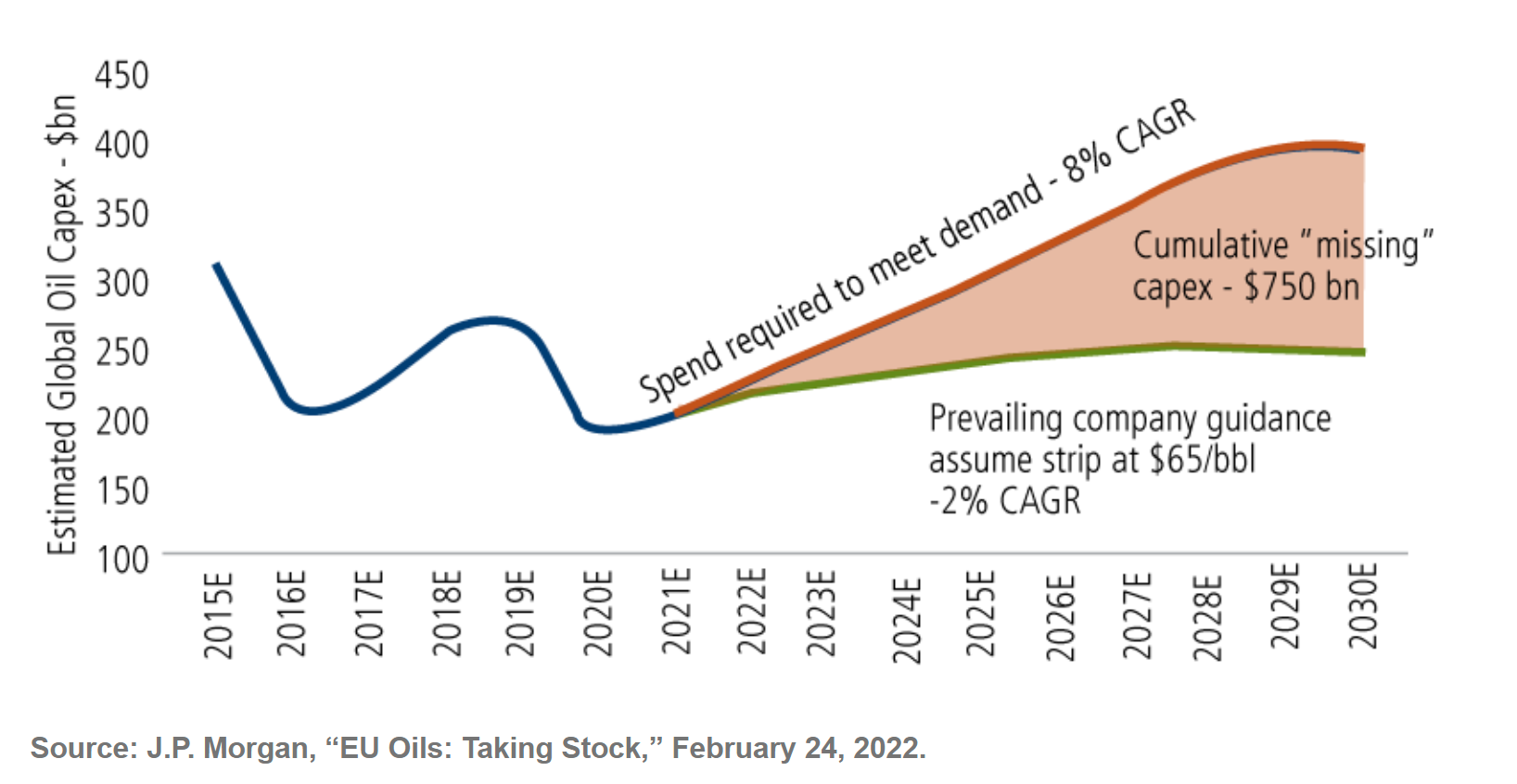

This leaves a hole in the future supply. At the current rate, the industry is underinvesting to the tune of $750 billion by the end of the decade (Figure 3). Having been burned for over-investment in the past, the industry has found ‘capital discipline’. Good for shareholders, bad for consumers.

This means prices may remain high for the foreseeable future. At these lower levels of Capex, the breakeven oil prices are in the range of 40-$60. At the current WTI price of $88.60 per barrel, that represents a roughly 33-55% margin of error.

On February 24th, Russia invaded Ukraine. On February 28th, Warren Buffett started buying Occidental Petroleum (Oxy), an oil and gas company with major production capacity in the US Permian Basin. You can hear Warren’s reasoning about the purchase from the man himself. Overall, Berkshire deployed about $9.5 billion and owns 19% of Occidental. Over time, Warren also bought about 8% of Chevron.

These two companies have something in common. They both have communicated clearly that they have a strategy to maintain dividend and share buyback even if oil falls another 33-50%. Here’s a quote from Mike Wirth, CEO of Chevron from a recent presentation (emphasize ours):

“We also have been very consistent in demonstrating that in a cyclical business, we are prepared for the downside. When we went through 2020 and oil prices went negative, we didn’t panic. There was never a question as to whether our dividend would be cut. In fact, we grew our dividend during the pandemic. We’ve grown our dividend 20% between 2020 and today – that stands out unique amongst our peers. In a downside price scenario, the $50 oil price, which seems hard to imagine today when it’s more than twice that, we continue to have the capacity to increase the dividend and buy back shares for five years at a $50 [Brent] price. And this is a chart that we shared at our Investor Day in March at an upside case of $75 [Brent], which doesn’t feel like upside versus today. We’ve got the capacity to buy back more than 20% of our outstanding shares over just five years. So we’ve got a very strong balance sheet, very strong cash flow, and the ability to continue to return cash to shareholders in any environment.” — Mike Wirth, CEO of Chevron

Cashing out

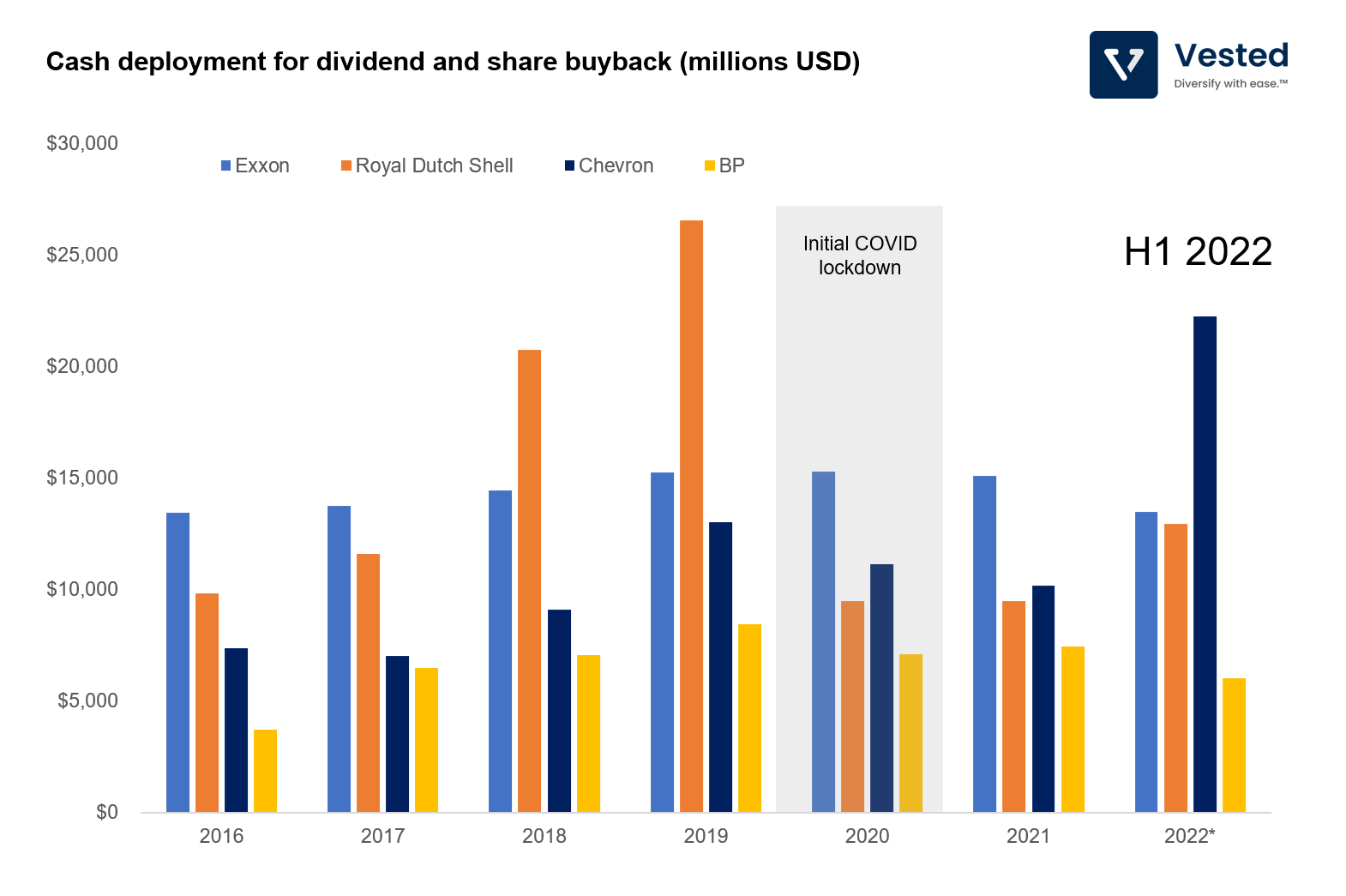

So what do you do with all this cash generated at the current high price levels if not invest in Capex? Return them to shareholders. Unlike the previous boom/bust cycle of the 2015s, despite the high prices of oil, the producers are maintaining fiscal discipline and are not investing in capital expenditures to increase future production.

Here’s a snapshot from four of the supermajors (Figure 4 below). They are returning cash at a high rate, especially Chevron.

What’s the long term future going to look like

In thinking about oil, a natural resource that is important for our industrial economy but is harmful for humans and the environment, it might be useful to look at another commodity that has similar characteristics: asbestos.

Asbestos is a naturally occurring fibrous silicate mineral. In the 19th and 20th century, it was ubiquitous. It was used as electrical insulation, fire proofing, household items, and building material.

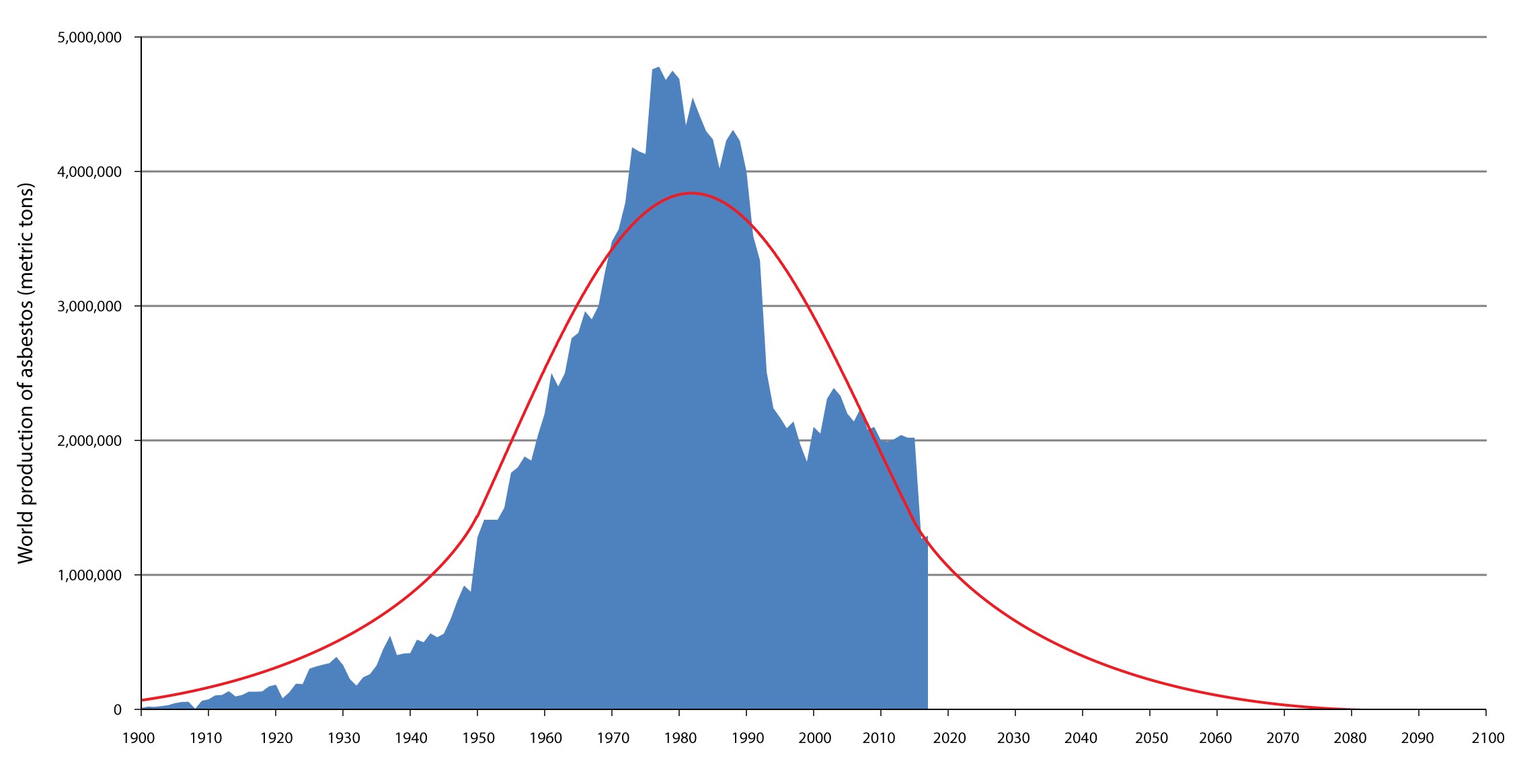

After centuries of use, the connection between asbestos exposure and lung cancer was only established in the late 1950s and early 1960s. But, production continued to accelerate for another decade (and peaked in the 1970s). Here’s a chart of the world’s asbestos production (Figure 6 below). It was only until the 1980s that the world’s production started to decline. It took another two decades for the last asbestos mine in the US to be shut down (in 2002). Today, asbestos mining and production is probably as close to uninvestable as you can get.

Despite this, production and consumption of asbestos continued, mostly in developing countries. As of 2020, Russia, Kazakhstan, China, Brazil, and Zimbabwe are among the five largest producers. And as you can see in Figure 5 above, the trendline for projected production will not reach zero until ~2080.

One should expect the same pattern to play out in oil & gas. Without government policies and enforcing additional environmental protection, the production and consumption will just migrate from developed nations to emerging countries. From a consumption standpoint, viable cost effective substitutes might not be readily available in these countries. From a production standpoint, the pollution and environmental damage related to the extraction will occur there (although, unfortunately, unlike asbestos, oil & gas usage warms the entire planet).

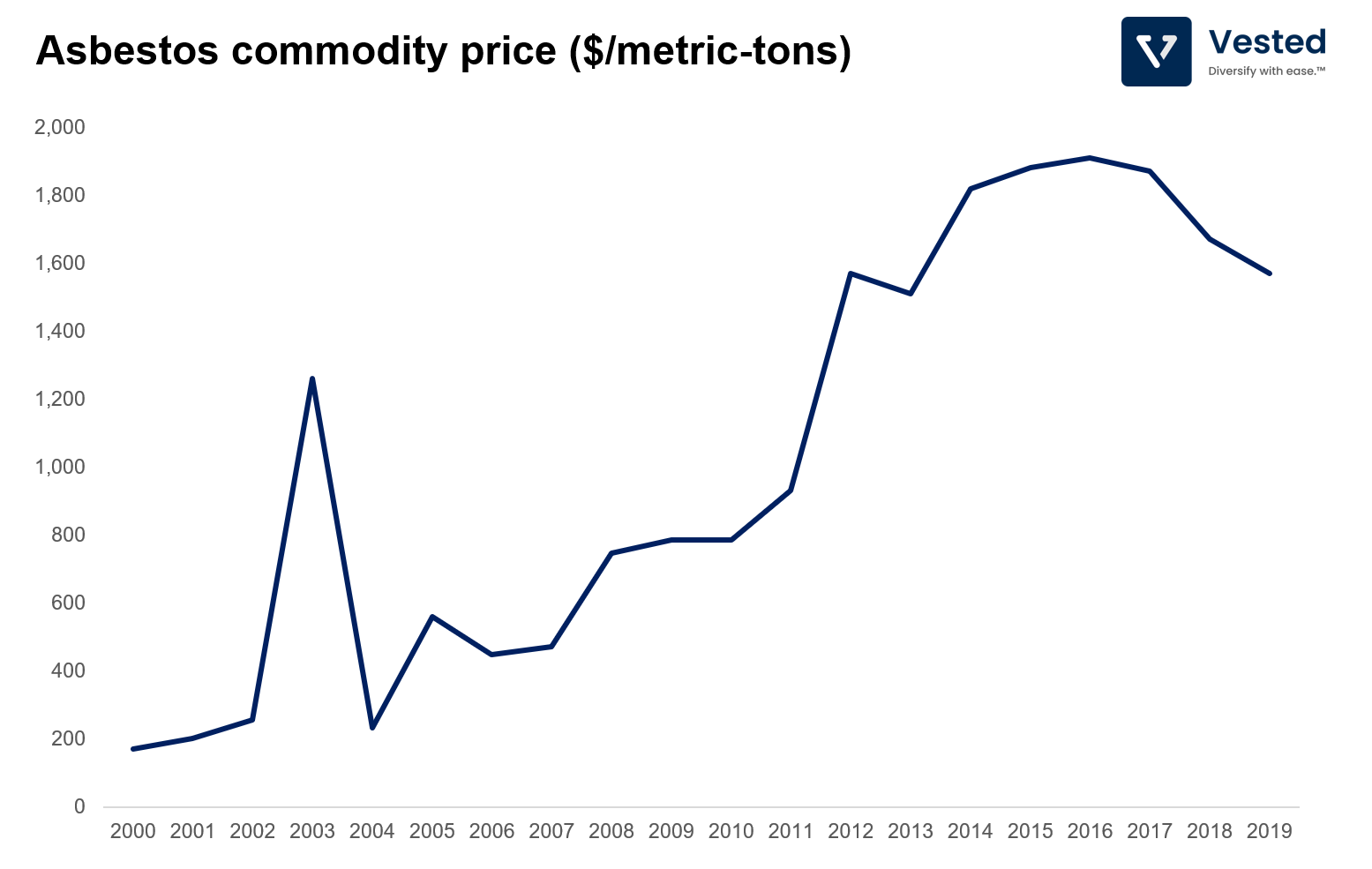

As demand dwindles, supply declines as well. But this won’t mean that prices will go down. In fact, the opposite might happen. Prices are defined by marginal supply meeting marginal demand, and, as we outlined above, marginal demand will decline, making prices increase for the remainder of the consumers. Here’s the price trend of asbestos (see Figure 6 below). From 2000 to 2019, prices have gone up more than 8x.

If the same trend plays out in oil & gas, expect production to decline, prices to go up, and over the coming decades, producers will focus on returning cash to shareholders.