In this week’s article we discuss why investing in IPOs is generally not a good idea.

With the recent uptick in the number of companies going public (whether by way of traditional IPO, SPAC or direct listing), more and more retail investors are interested in investing the same day when companies are available to be publicly traded.

Generally, this is not a good idea. To understand why, we must first understand what factors affect returns.

The Returns Equation

The returns that investors realize from their investments can be derived from three core sources:

- Shareholder yield: This is excess cash that the company spends on buying back shares or giving out dividends. The more cash a company spends to return to shareholders via this route, the more returns the investor will generate.

- Growth: This is the growth of the company that can be measured on the earnings results (revenue, earnings, book value).

- Valuation change: This is the trickiest of the three, as it involves human assumptions. Some investors use financial models that take input of interest rates and some assumption of a company’s growth rates to justify valuation changes (this is why changes in interest rates affect stock prices). Others use narratives, stories, memes, or are driven by FOMO (fear of missing out) to assess change in valuation. The valuation change factor is the one that often gets investors into trouble, leading to investing in companies that are overly hyped.

Return = Shareholder Yield + Growth + Valuation Change

So what does this have anything to do with investing in IPOs?

- It is often the case that the hype is the highest when a company is going public: There is a lot of media attention and social media chatter.

- The Valuation Change component is distorted the most close to IPO (typically due to a higher valuation).

- At the same time, this is also the period where data around the Growth component is at the lowest level of availability.

On average, IPO investing underperforms the benchmark

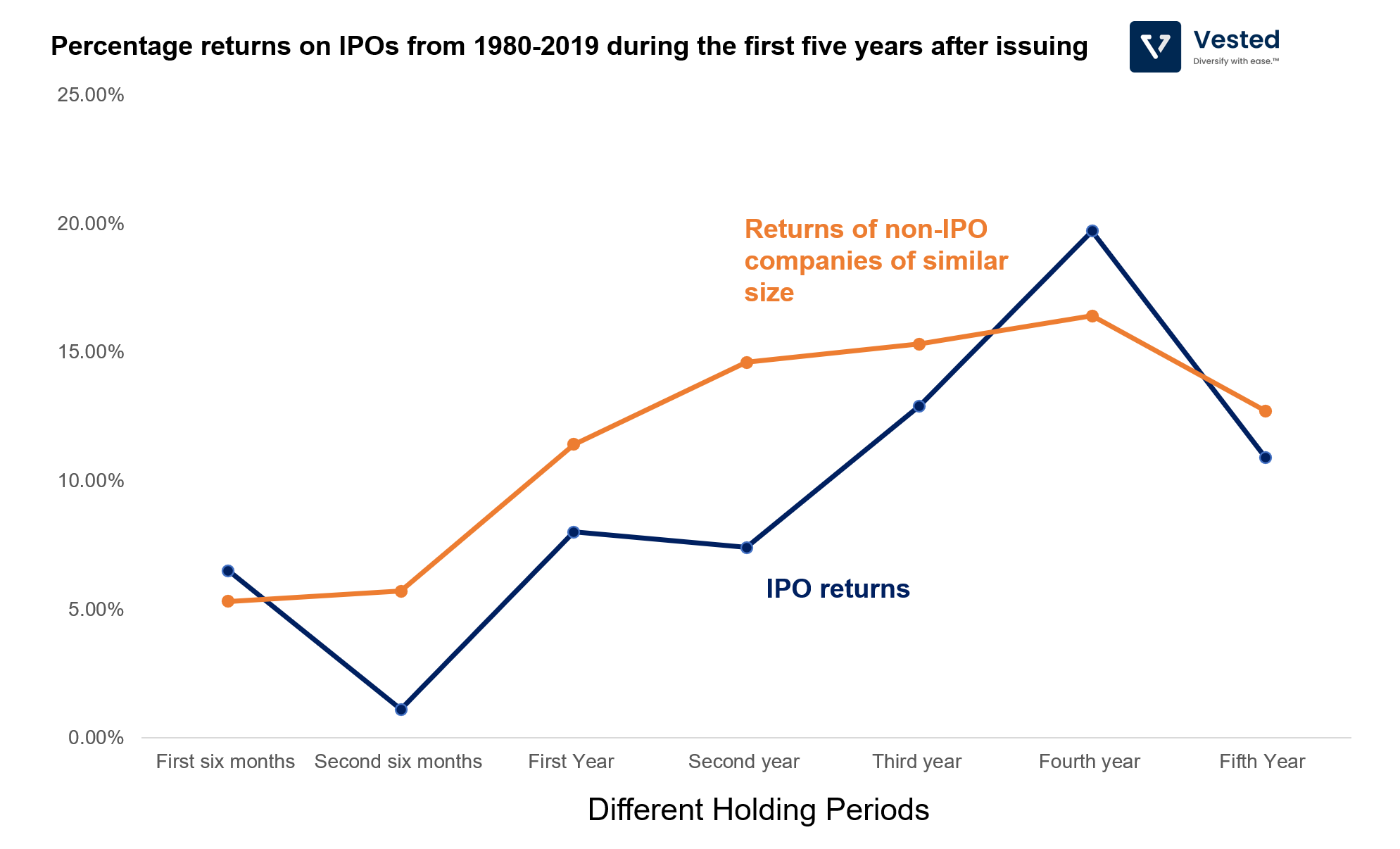

Here’s the return data for IPO investing from the past 40 years (for over 8,000 IPOs). See Figure 1. The blue line represents the percentage returns if you had invested in all the IPO companies and held them for different time periods. Meanwhile, the orange line represents the percentage returns if you had invested in other non-IPO companies of similar market cap.

As you can see in Figure 1, for most holding periods, investments in IPOs yielded a worse return compared to returns of non-IPO companies of similar size (the blue line is mostly under the orange line).

Underperformance has largely been true for 40 years

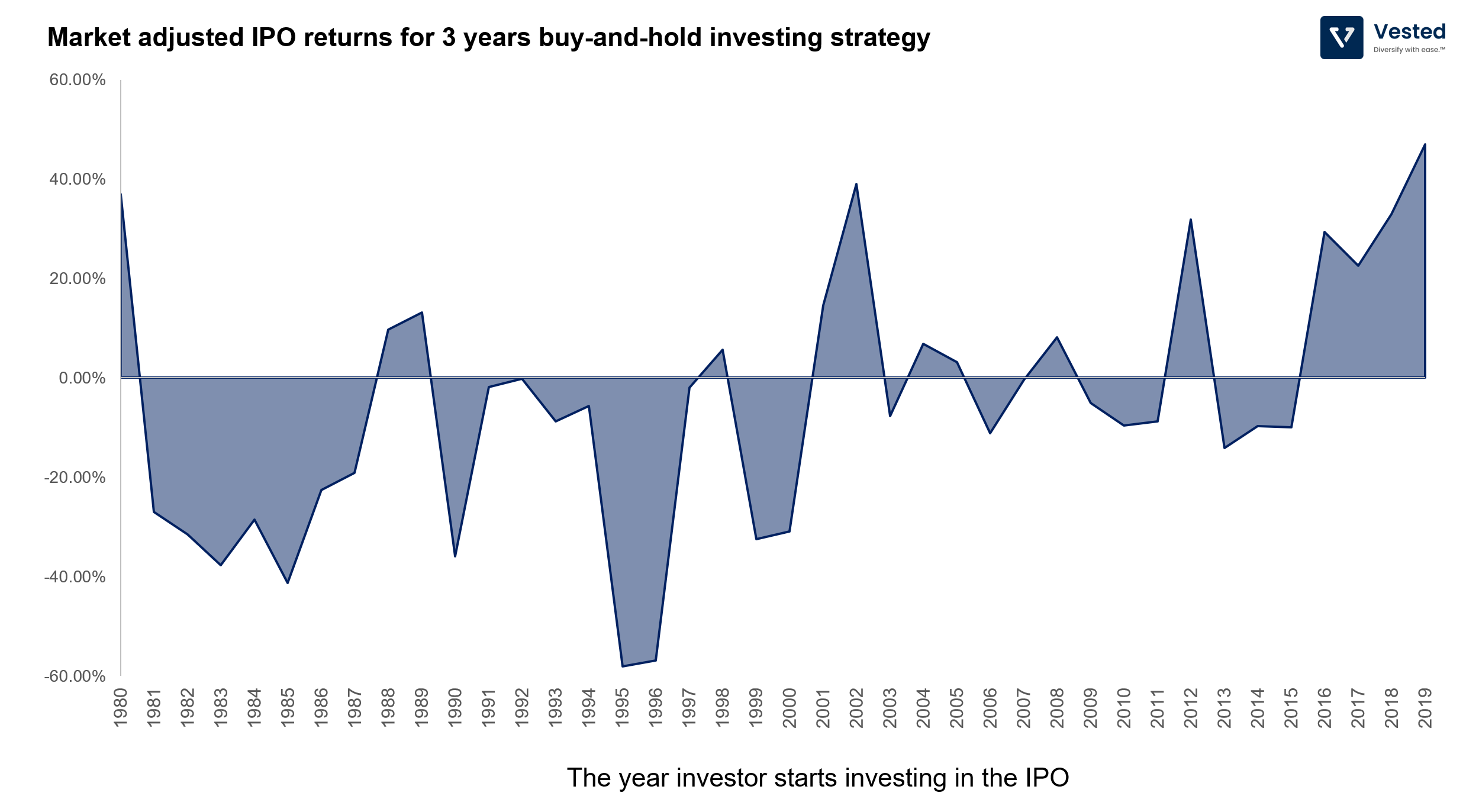

Ok, you might be thinking, 40 years is a long time. We shouldn’t be averaging over this large of a timespan since the investing world has changed drastically over that time span. So here’s the 3-year return of a buy-and-hold investing strategy in IPOs over the different years (Figure 2).

Note: Buy-and-hold returns are calculated from the first closing market price until the earlier of the three-year anniversary or the delisting date.

Figure 2 shows the difference between investing in IPOs for a particular year minus investing in the benchmark in the same year. If the value is negative, investment in IPOs underperforms investing in the benchmark (assuming a 3-year buy-and-hold strategy).

Here are two key takeaways:

- Notice how the area that is negative is much higher than positive? For the most part, investing in IPOs underperform the benchmark by a significant amount.

- Out of the 40 different start years, there are 26 years where you have negative returns (65%).

Investing in small IPOs is even worse

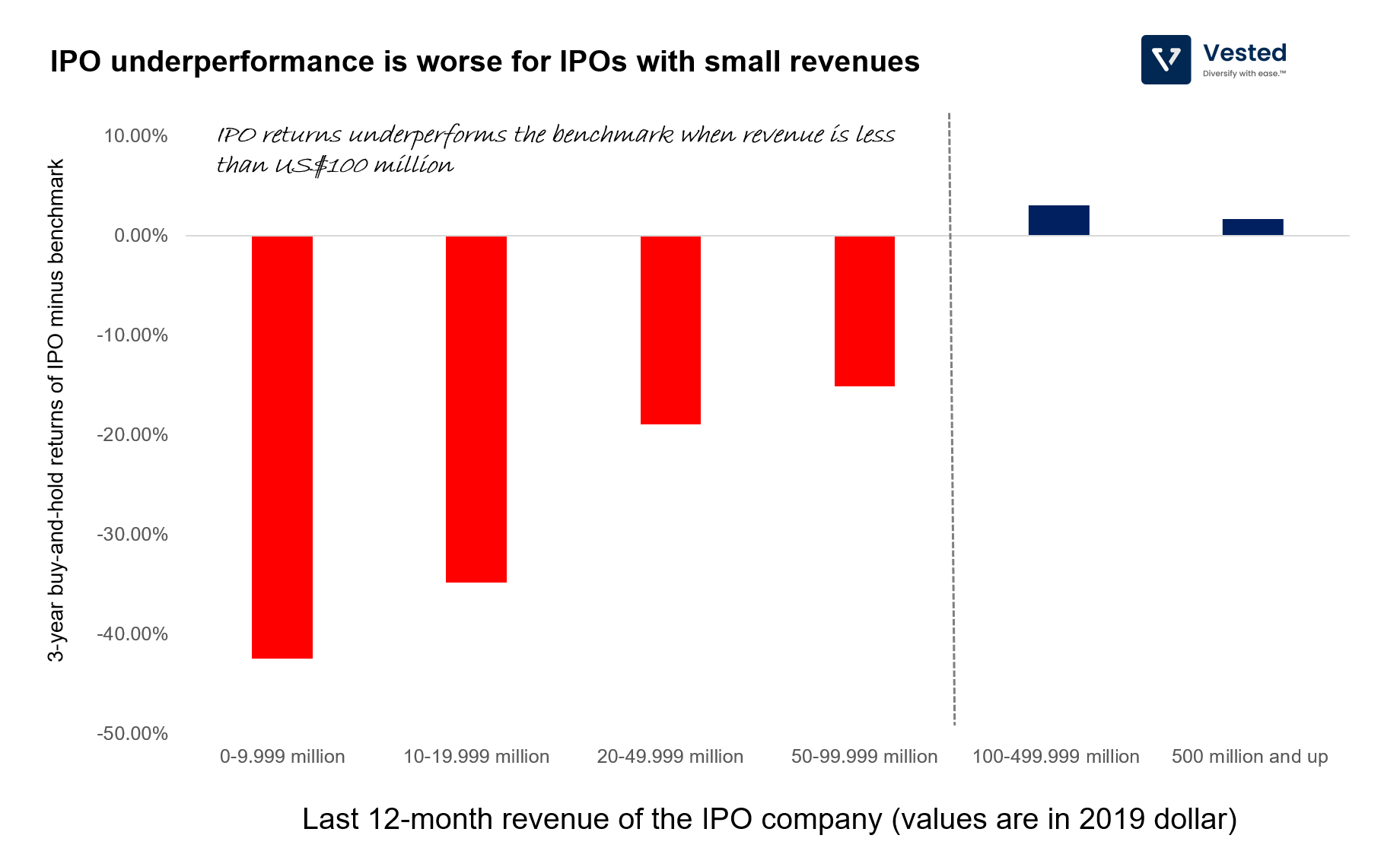

If you dissect the data even further, there’s a particular skew of IPOs that are really bad. Figure 3 shows the 3-year buy-and-hold returns of IPOs minus the benchmark. Again, positive means that the IPO investments beat the benchmark, while negative means they underperformed.

On average, IPO investments in companies with small revenues (less than US $100 million in LTM revenues leading to the IPO) really underperform the market. So maybe, investing in pre-revenue, pre-product, SPACs (and the like) is a really bad idea.

Investing in larger Tech IPOs is not so bad

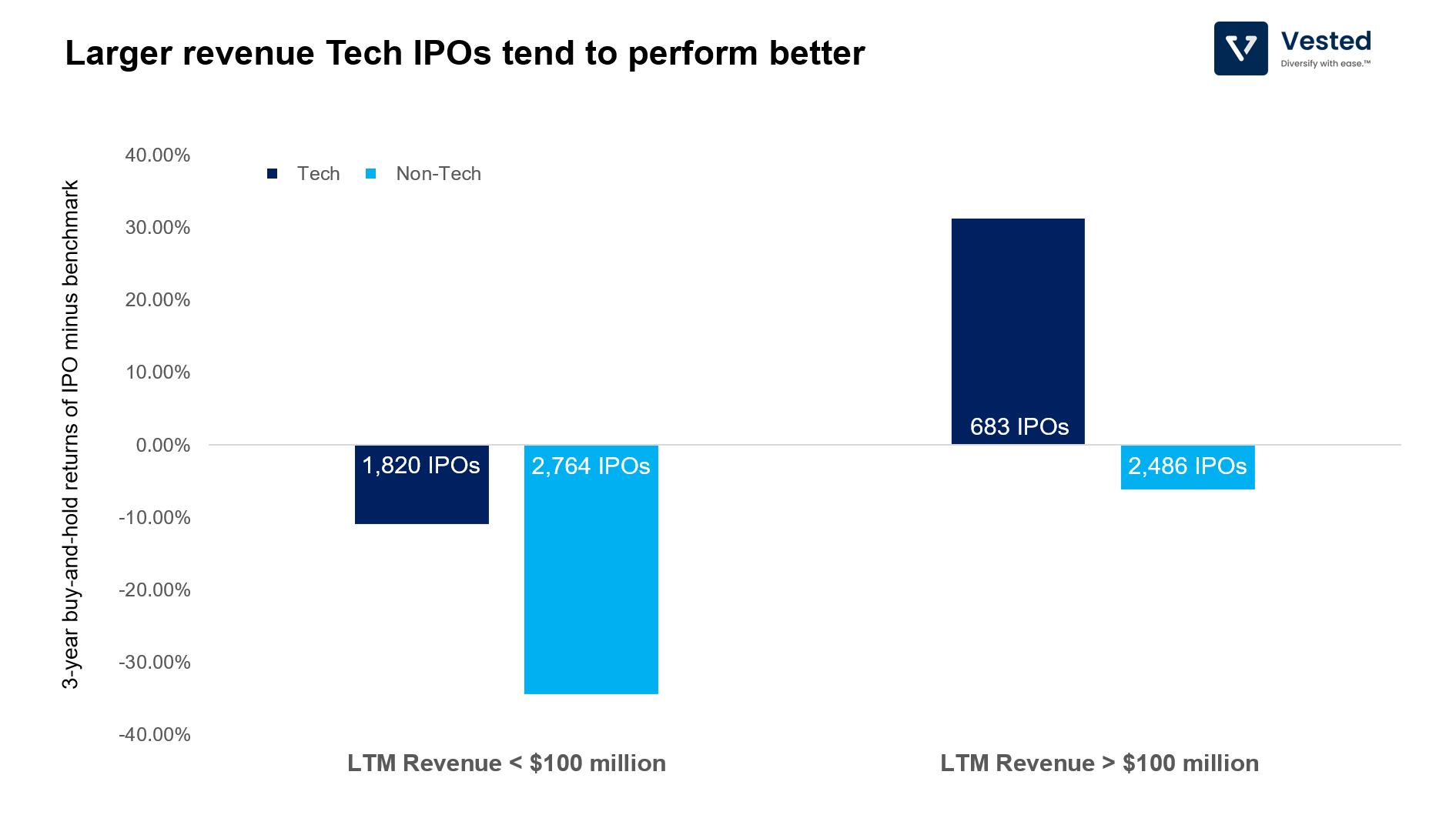

And finally, you can future segment the IPO data set based on tech companies vs. non-tech companies (see Figure 4). On average, only larger tech IPOs (> US$100 million LTM sales) outperform the benchmark after 3-years buy-and-hold.

The final word

- Wait. Generally, investing in IPOs yield worse returns than investing in the broader market. Investing in an IPO means you are investing near the peak of the hype cycle. It may be best to wait (it’s not like they’re going to run out of shares to invest in months down the road). Waiting also allows you to gather more data on the company.

- Don’t invest in small IPOs. The data is quite conclusive. Investing in IPOs with very small revenue tends to lead to underperformance, no matter how attractive the narrative sounds.