In this week’s article we will be discussing super apps and Grab.

What are Super Apps?

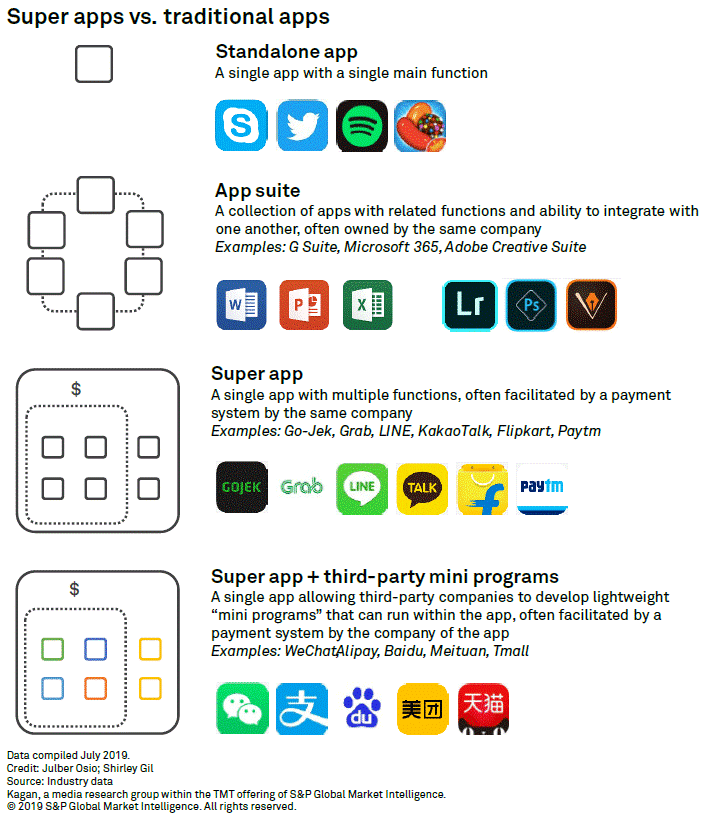

Super apps are apps that offer multiple functionalities in a single app. These apps strive to be the operating system of your life (Figure 1).

Super apps typically start off by providing a core function that meet two criteria:

- A function that is used often (multiple times per day), enabling the app to gain mindshare/habitual use.

- A function that has embedded network effects, allowing the app to grow its user base rapidly.

Once the initial function achieves a significant user base, the super app operator then expands into adjacent use cases in order to gain more of the user’s share of the wallet (games, ecommerce, food, hotels, groceries, etc).

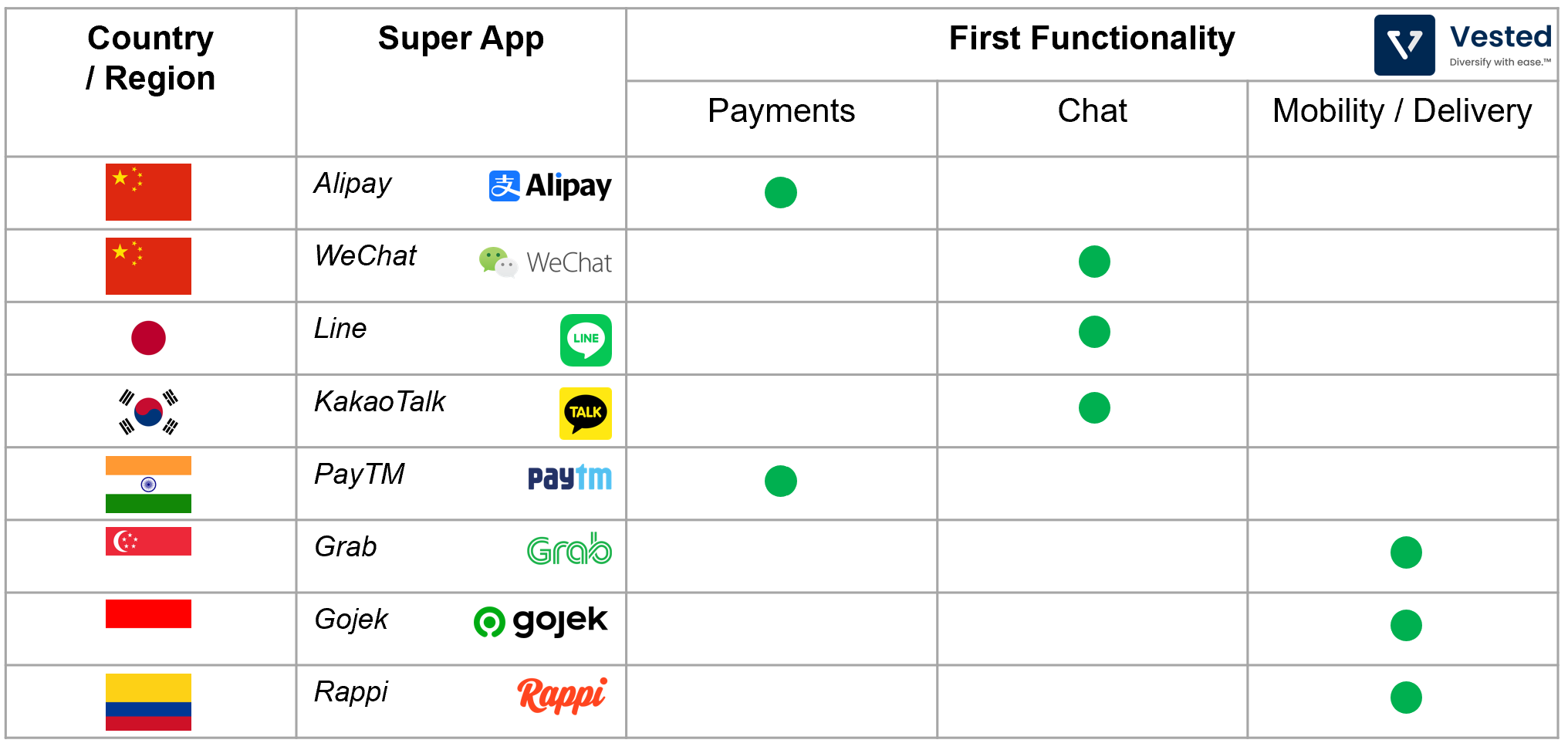

Notice, however, that these apps only exist in Asia and not in the West (even Uber splits its ridesharing app from its Eats app in the US). This is because:

- When super apps first enter their respective markets, oftentimes they are the first digital provider for these services (financial services, digital payments, ride hailing, chat, etc.). As such, the low initial digital penetration helps super app operators convert first time users to loyal users.

- Asia is mobile first, while the western world was desktop PC first. As a result, users in the west are more accustomed to using a specific application to carry out a specific task.

- There is more scrutiny towards anti-trust and concerns about handling, storage and use of personal data in the West. This is especially true in recent years, as many US-based tech giants are facing increased scrutiny over their acquisitions.

But hey – enough about super apps. We’re here to talk about Grab, a super app operator that is going public by merging with Altimeter Capital’s SPAC.

Grab’s History

Grab is one of the dominant super apps in Southeast Asia. The other is Gojek, and the two share a rich and competitive shared history.

Anthony Tan first met Nadiem Makarim at Harvard in 2009, when both of them attended Harvard Business School. The two struck a friendship over their interest in entrepreneurship and over the fact that they come from neighbouring countries (Tan is from Malaysia, while Makarim is from Indonesia).

After their time at Harvard, Tan returned to Malaysia, and in 2012, started Malaysia’s version of Uber called MyTeksi. Unlike Uber, however, MyTeksi connects Taxi drivers with passengers. The app was then renamed to Grab Taxi, and later as Grab.

Meanwhile, around the same time, Makarim started a small call center, Go-Jek, to connect riders with motorcycles for hire. He did so on a part time basis, while working to start companies for the eponymous Rocket Internet. In 2014, he left Rocket to work on Go-Jek full time. At the time the funding environment for ride sharing was very hot, as many investors were trying to catch Uber’s wave.

Over the years, both companies have evolved into super apps, operating in overlapping countries in Southeast Asia. This put Makarim and Tan into a collision course. The two used to joke that Grab would dominate taxis while Gojek would dominate motorcycles. But now, they’re no longer on speaking terms. The competition between the two firms are well chronicled. Both firms burn billions of dollars annually to offer incentives and promotions in a brutal competition to gain market share. Last year, Softbank urged the two to merge and consolidate their businesses in order to improve profitability. But discussion broke over disagreements around the structure of the merger.

And now, Grab has announced that it will go public, which gives us the opportunity to look at its financials.

Grab’s Business

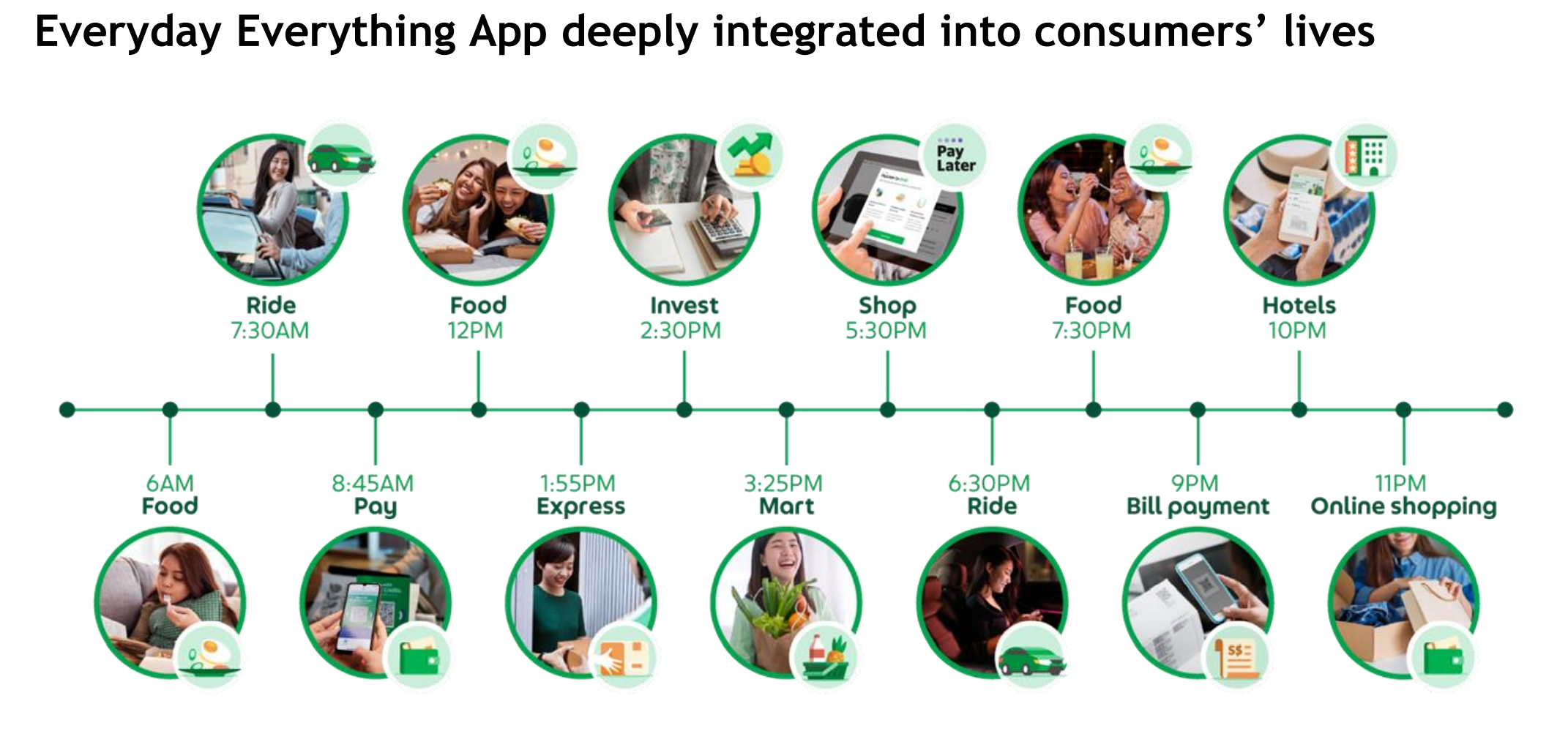

Grab strives to be the operating system of your life. It wants to give you a ride to work, help you order your meals, manage your finances, and make shopping easier for you. Here’s what your day would look like if you did everything with Grab (Figure 3):

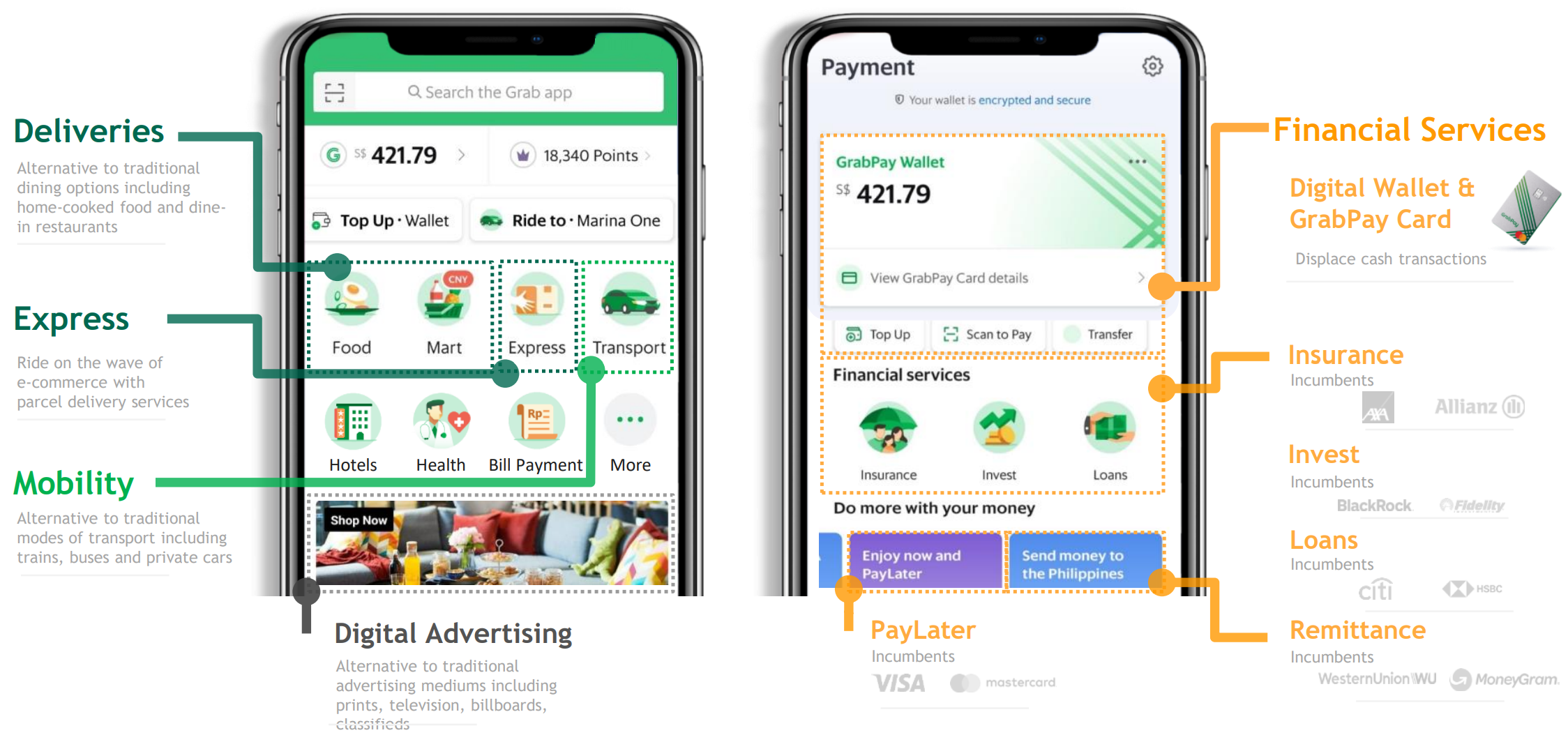

And it wants to do so in a streamlined user interface (Figure 4). However, one can argue that this might deter the use case of some core functionalities. More options mean more clicks one has to make before getting to the functionality that one needs at any moment. Imagine clicking through multiple menus to summon a car in the middle of a monsoon rain in Jakarta…

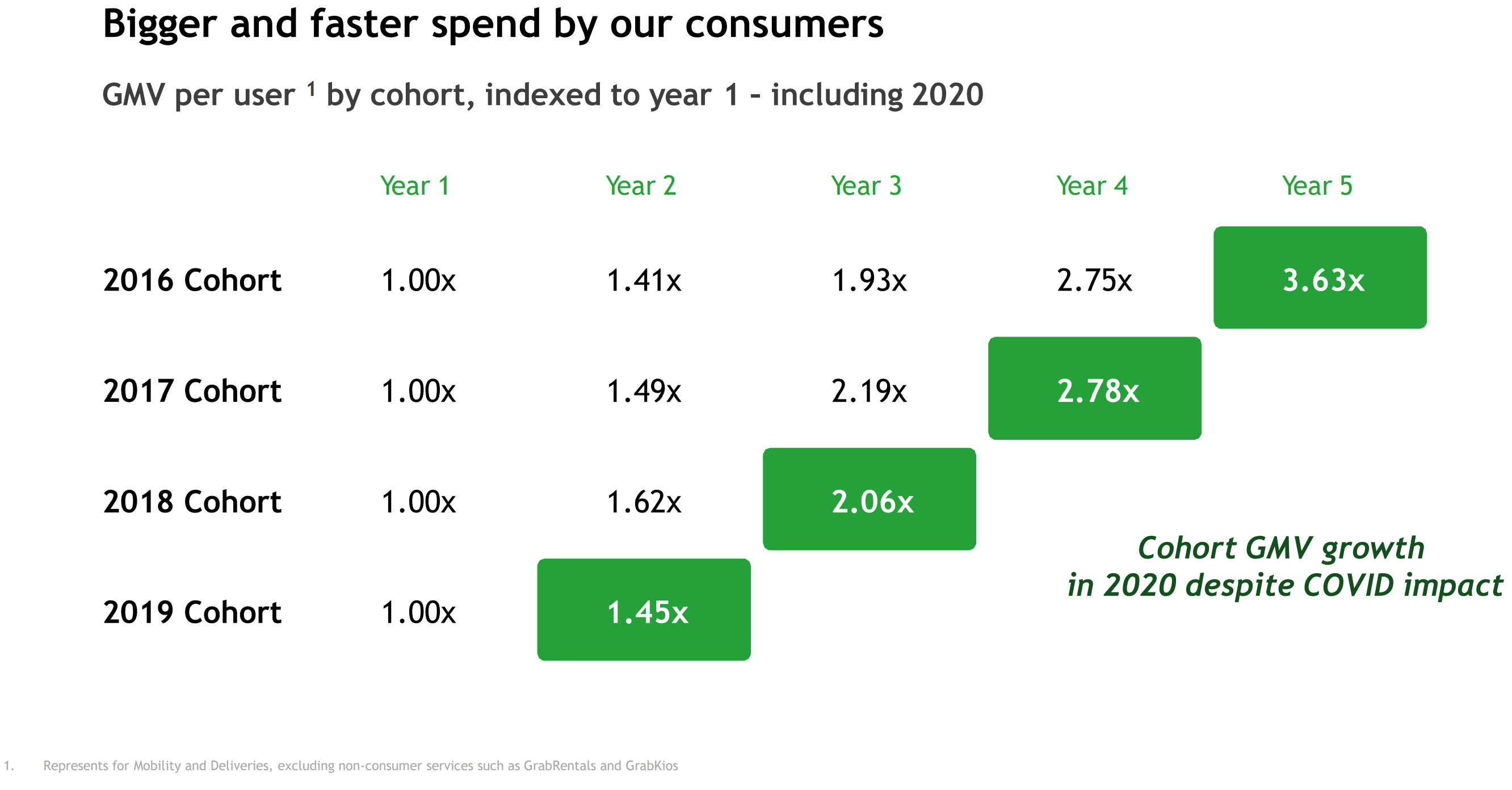

Nevertheless, additional functionality within the app increases user engagement (Figure 5). Five years after starting to use Grab, the user cohort from 2016 increased their in-app spending by 3.6x. Despite COVID’s impact in 2020, customer spending – measured by Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) – of the 2019 year cohort grew by 1.45x (from 2019 to 2020). This is due to an increase in the delivery business that helped counteract the decline in the mobility business.

Needless to say, the company’s finances are really complex. It generates revenue from many services in many regions (13 different product lines in 8 countries in Southeast Asia). But at a high level, you can breakdown Grab’s business into four main segments:

- Deliveries

- Mobility

- Financial Services

- Enterprise & Others

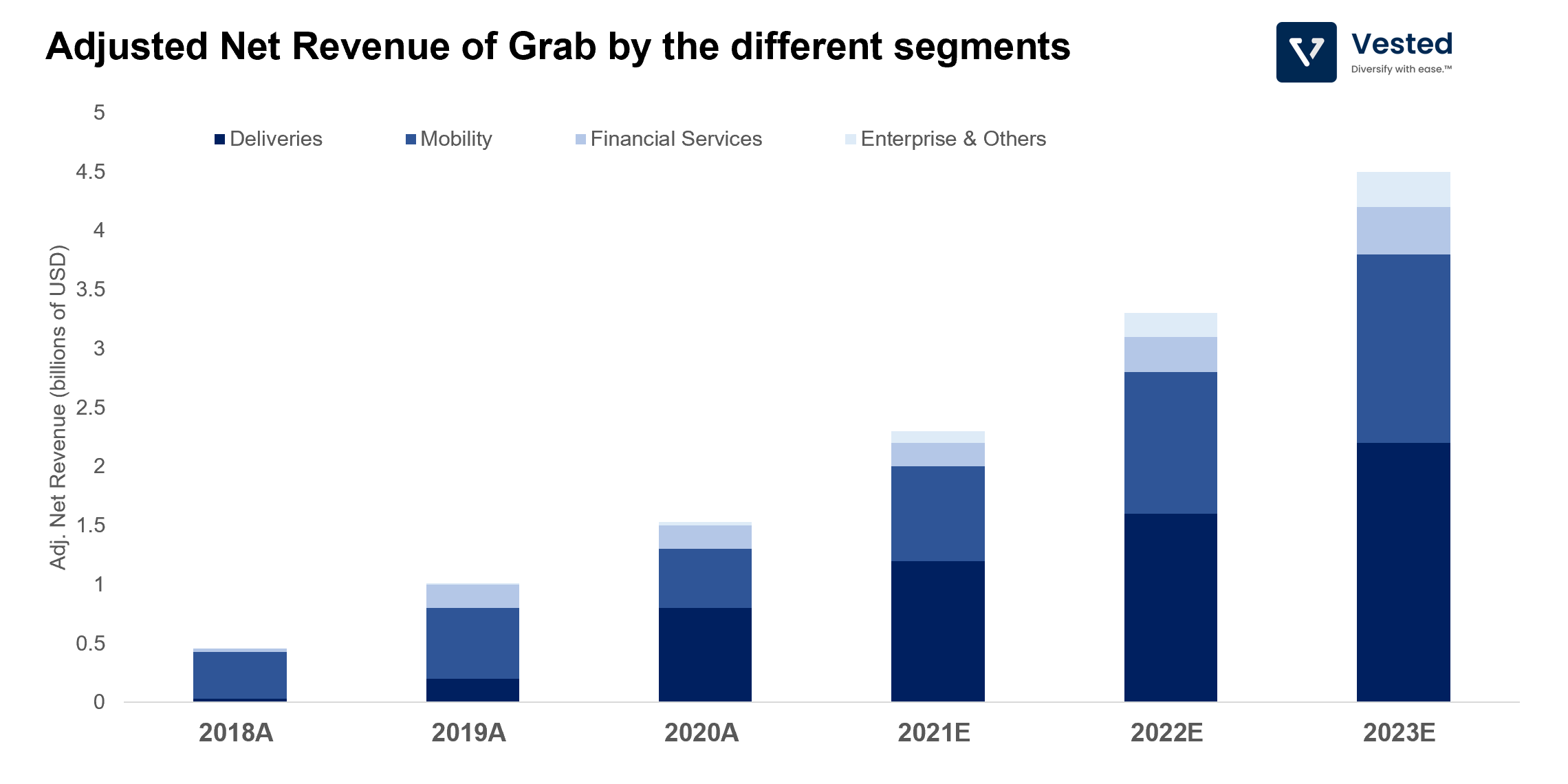

The breakdown of Adjusted Revenue by the different segments can be seen in Figure 6.

- The Delivery segment is the fastest growing segment. Despite only contributing 20% of adjusted Net Revenue in 2019, the segment grew rapidly and contributed about 50% of net revenue in 2020. The company expects the Delivery segment to maintain that level of contribution moving forward.

- The Financial Services segment is very new and is currently the least profitable segment, but is important for the company. Frictionless payments for services is key to increase customer spending. This is especially true in a region where penetration of electronic payments is very low (in Southeast Asia, electronic payment penetration is about 17%, which is 2.5x smaller than in China, and almost 5x smaller than in the US). Grab reports that users who use its payment solution spend 2.2x more than the ones who do not.

- Total Adjusted Net Revenue in 2020 is US$1.6 billion. Since Grab’s two core businesses are Mobility and Delivery, we will be comparing the company primarily with Uber. For the year 2020, Uber’s revenue was US$11.1 billion (or about 7x higher than that of Grab’s).

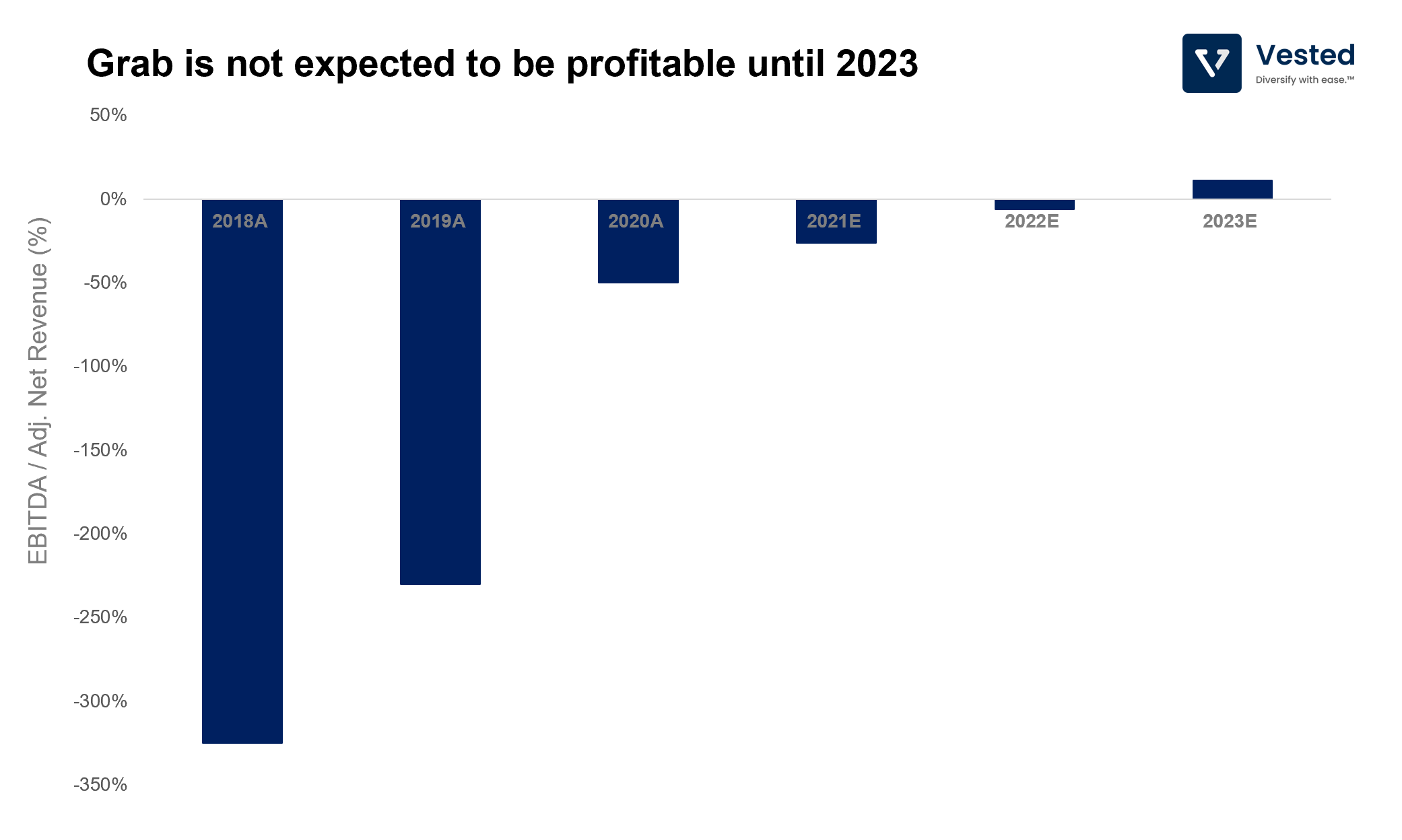

Overall, the company is not profitable, and management does not expect it to be so until 2023 (Figure 7). It is certainly questionable whether US investors have patience for another money-losing ride sharing/delivery company.

The hard thing about hard things

Despite the allure of super apps, make no mistake, Grab’s business is really hard. The company operates in a challenging region where the consumer, on average, has lower purchasing power.

Southeast Asia (SEA) is not China

China is one of the few places where super apps have flourished. Both Tencent’s WeChat and AliPay are two prime examples. In the investor presentation, Ming Maa, Grab’s President, compared the SEA region to China in an attempt to draw favorable comparisons. He said that “Southeast Asia is China 5 years ago. In Food delivery, tremendous penetration headroom yet to go.â€

In terms of penetration, the penetration in SEA is much lower than that of China. But that is because the SEA region has different characteristics.

- Unlike the relatively homogenous China, SEA is more akin to Europe before the EU. It comprises multiple competing countries that speak different languages, separated by oceans, with different cultures, religion, currencies, regulations and ethnicities. This diversity and fragmentation means that what makes a company successful in one country may not propel the company to success in another.

- SEA also has a much more challenging geography with less developed infrastructure than China. For instance, Indonesia alone comprises more than 17,000 islands, which makes travel and logistics more challenging.

- Cities with similar densities as China are not as plentiful. China has more than 113 urban areas with more than 1 million inhabitants in each. The whole SEA region only has about 31. Density typically translates to lower logistical costs.

We’d argue that SEA is not China 5 years ago – it’s a different kind of beast.

Lower Average Revenue per User (ARPU)

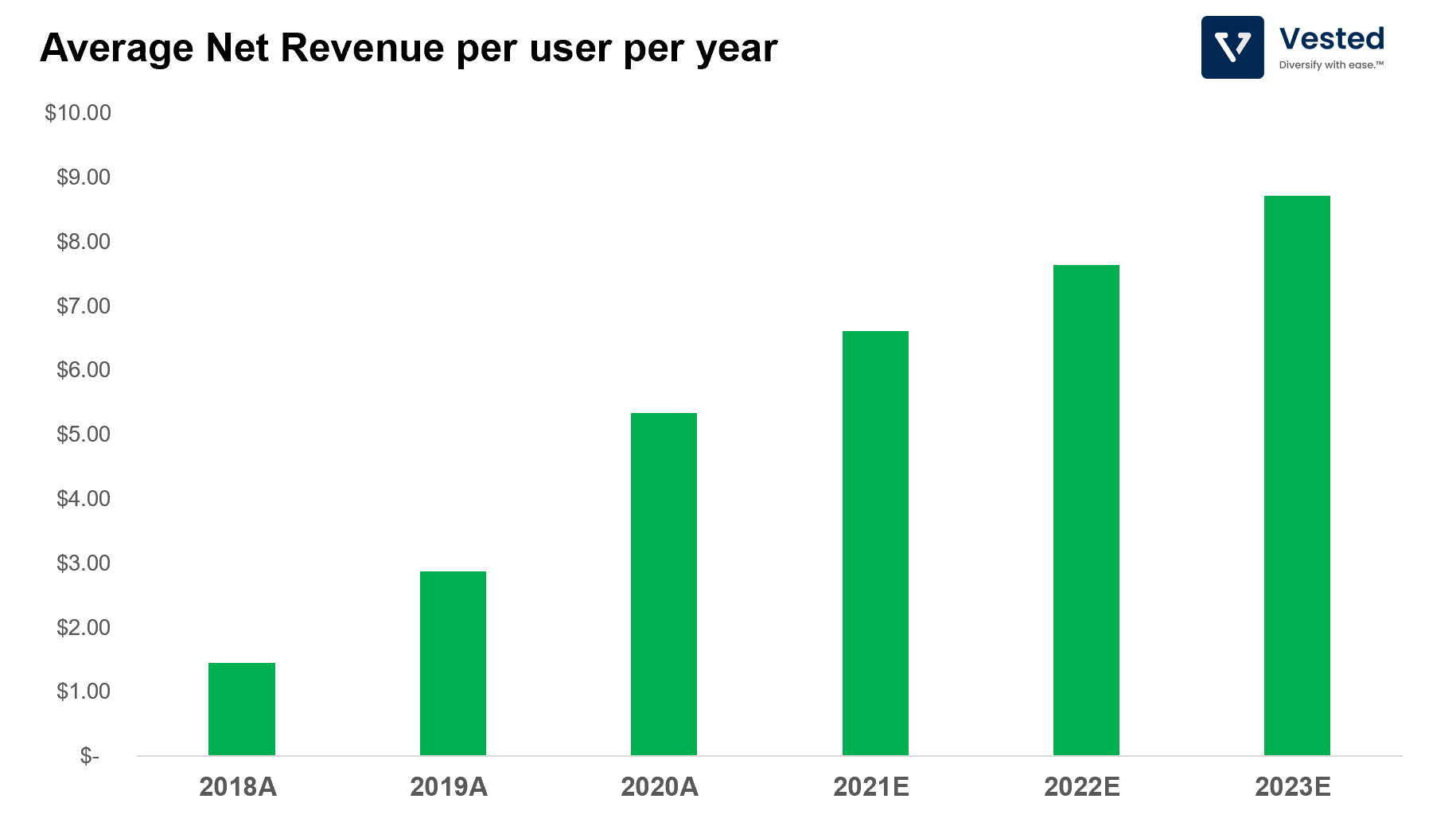

On top of that, the Average Revenue generated by the average user is much smaller than other companies that investors can invest in (see Figure 8 for estimated ARPU).

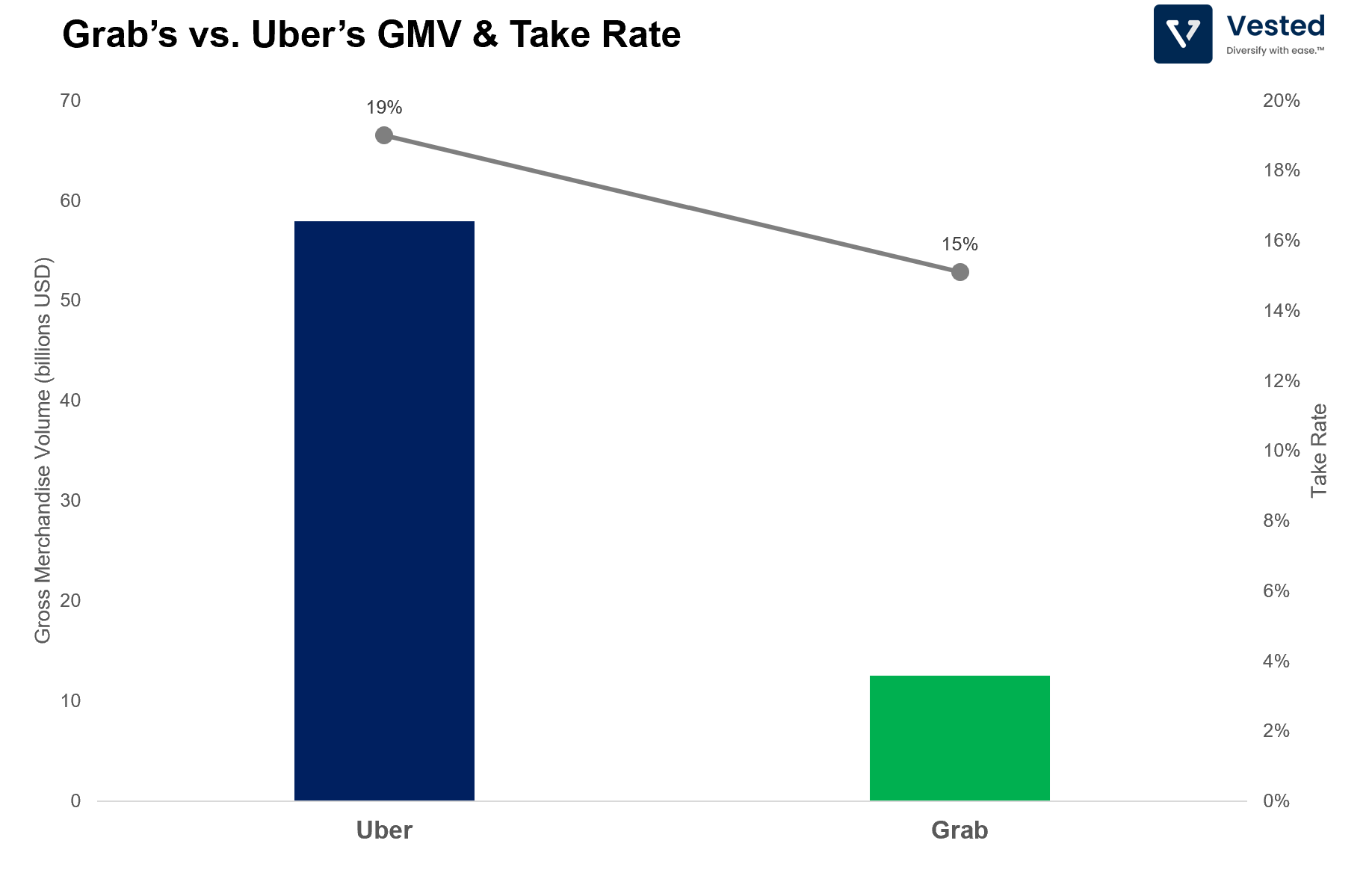

This is because of two things: (i) Grab’s total GMV is lower and (ii) the Take Rate is also lower (see Figure 8).

As a result of lower GMV and lower Take Rate, Grab’s ARPU is much lower than that of Uber’s (Figure 9). We estimate that Grab’s ARPU is about US$5 per user in 2020, a far cry from Uber’s ARPU of about US$126 per year (which is largely derived from the US and Europe, regions Grab do not operate in), and still lower than Facebook’s ARPU generated in the Asia-Pacific region (US$13.8 in 2020).

The challenging operating environment in SEA is why Uber retreated from the area, and sold off its operations there to Grab in 2018 in exchange for a significant stake in Grab. Uber still owns about 16.6% of Grab, so an investment in Uber represents a significant investment in Grab.

One final note: On announcement of the merger, Grab was valued at close to US$40 billion, which is only 2.5x smaller than Uber’s market cap. After evaluating the internal metrics and top line numbers of the two companies, the gap in valuation seems to suggest that either Grab is overvalued, or Uber is undervalued. Possibly both.