In this blog, we discuss the Q1 2023 earnings of both Netflix and Tesla. After reviewing their latest earnings, there are some common narrative threads one can observe:

- Both were early movers in their respective verticals and after years of building their own integrated supply chains, both have a cost advantage over their competitors.

- As the cost of capital increases (due to increasing interest rates), both companies are pressing for the cost advantage by lowering their prices to gain market share.

- And, even though prices are lowered, they expect to generate more revenue and profits through secondary offerings.

Tesla’s Q1 2023 Earnings

| Expected | Actual | Observation | |

| Revenue | $23.33 billion | $23.21 billion | Miss |

| EPS | $0.85 | $0.85 | Target |

One (of many) things that make Tesla unique is its predisposition to change its prices rapidly, often without notice. A practice that other car companies do not do. One thing dominating the news is the recent Tesla price reductions (six times in the past year alone). This is viewed as the company accommodating softening demand as Tesla faces more competitors. Of course, this has long been part of the discourse with the company. With more competition, its margins will be eroded over time.

Tesla management has a more nuanced view of the matter, however. In the Investor Day presentation, which we covered here (Tesla Strategies), Musk mentioned that, as far as the company is concerned, demand for Tesla is not constrained by desire but rather affordability. As interest rates continue to increase, monthly payments that consumers have to endure go up.

Elon and management commented that they had not seen any weakness in demand. Rather, Tesla was observing sales slowness due to affordability. Higher interest rates make financing more expensive, while at the same time, inflation is pushing costs up. In other words, demand for Tesla is constrained by affordability, not desire.

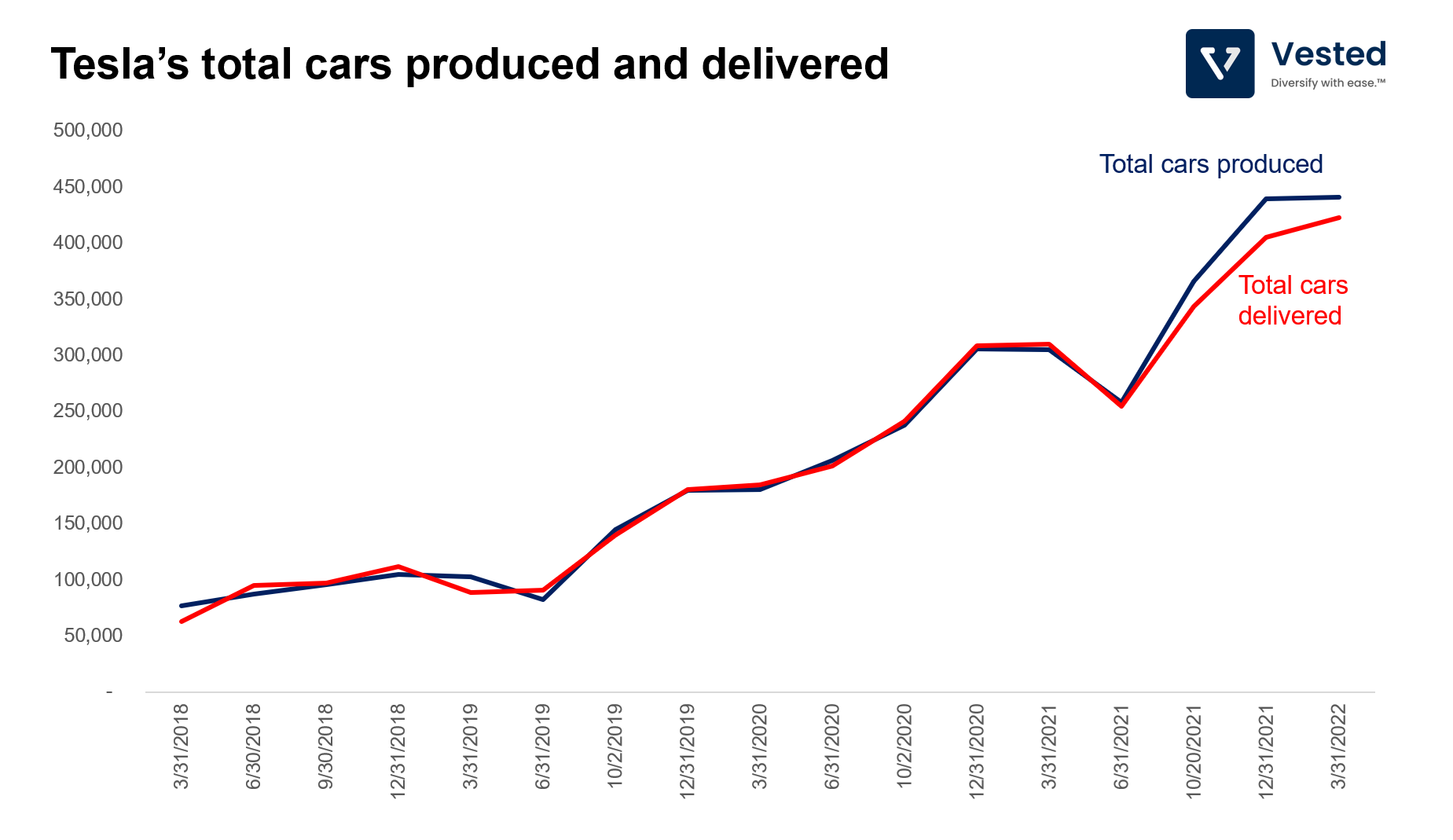

To address this affordability issue, the company has been aggressively lowering prices. Model Y, the 4th top-selling car in the world (beating Toyota’s Camry), has seen a ~29% price cut this past year. To see if price cuts work, we can look at the total vehicles produced and compare the numbers to the total delivered (Figure 1 below). Delivery numbers represent the point when customers accept the vehicle and are the point where revenue is recognized.

As we see above, the two lines started diverging in the second half of 2022, Indicating Tesla is making more cars than it can sell. The weakening of the global economy at the time likely caused consumers to cancel their orders. Tesla began to aggressively lower prices to reverse this trend, and it appears that its strategy worked. This past quarter, total cars delivered (red) went up, while total cars produced (blue) remained relatively flat.

Ok, so we’ve established that Tesla needs to cut prices. Can it do so? What’s the long-term impact on the company?

In the latest earnings report, management believes that (i) it has a cost advantage over competitors and (ii) it has higher long-term revenue potential on its cars than other EVs. These two reasons allow Tesla to be more aggressive with pricing without jeopardizing its long-term profitability outlook.

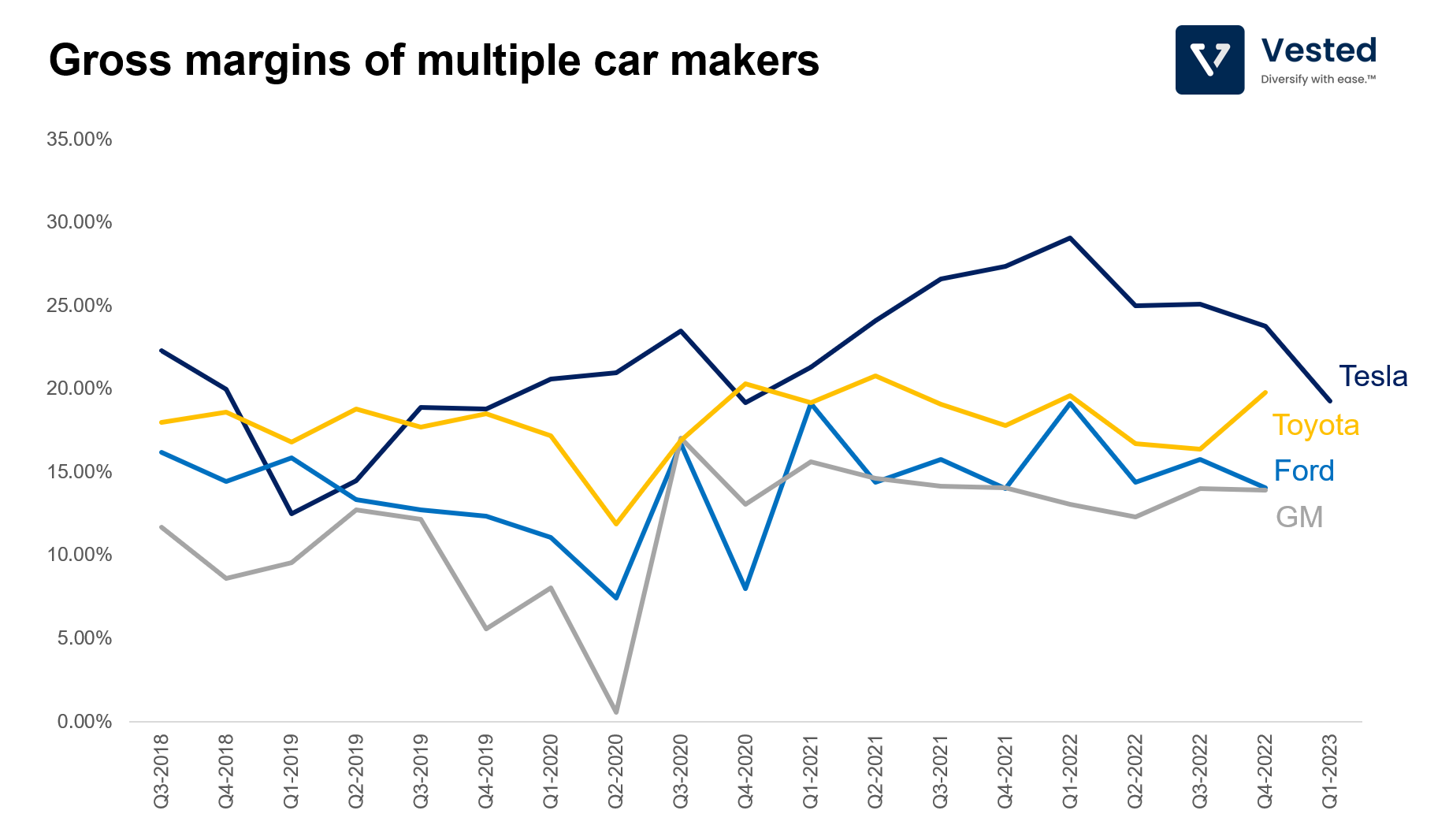

Indeed, Tesla has a cost advantage over its competitors, which shows up in higher gross margin levels (see Figure 2 above). Over the past few years, it has expanded its gross margins from ~20% to a peak of 29% in Q1 2022. However, the margin level has decreased over the past year due to inflationary pressures, higher capital investments for 4680 battery cell ramp-up, and price cuts. In Q1 2023, Tesla’s gross margin declined to 19%.

While the margin levels of Tesla and others might appear to be converging, we should expect the margins of other car makers also to decrease. The numbers above are a mix of EV and ICE (internal combustion engine) cars. In reality, EV cars made by Ford, GM, and Toyota are not profitable. Ford’s EV division lost $3 billion in Q1 2023, while GM does not expect to make any profits on EVs until 2025. GM’s most popular model, the Bolt, is being sold at a loss. Meanwhile, Toyota does not expect to launch its EV platform until 2027-2028. As these companies sell more EVs, the overall margins will decline. From the perspective of EV cars, Tesla is the only profitable car maker.

Tesla’s management decided to lower prices and aggressively pursue market share to exploit its competitors’ lack of profitability and production capacity. They believe that:

- They have the process advantage. Tesla can continue to lower manufacturing costs (in the five years the Model 3 has been in production, manufacturing costs have gone down by 30%).

- They have a scale advantage. In manufacturing, you get operating leverage if you maximize the utilization of factories.

- Most importantly, if each Tesla vehicle can be monetized over longer periods via high margins software subscription, charging, and insurance, then it behooves the company to maximize market share during periods when competitors are not profitable.

Netflix’s Q1 2023 earnings

| Expected | Actual | Observation | |

| Revenue | $8.16 billion | $8.18 billion | Beat |

| EPS | $2.88 | $2.86 | Miss |

Netflix’s business is changing. After 26 years, the business has evolved massively:

- In the beginning, it was a DVD-by-mail company. At the time, content delivery via the Internet was not feasible at scale. So while Netflix waited for the internet infrastructure to catch up, it decided to deliver a 5 GB content package (the size of a typical DVD movie) via US mail, which cost $0.32 at the time (faster and cheaper than it would’ve been compared to delivering via the internet at the time).

- Over time, the internet’s infrastructure caught up to Netflix’s vision, allowing it to begin delivering content via streaming. To bootstrap the service, the company acquired streaming rights from linear TV service providers, taking advantage of time arbitrage. Linear TV could only show one show at a time, while Netflix could show all shows to any user at any given time. This made the older content library more valuable for Netflix, allowing it to jumpstart its streaming service. In the meantime, linear TV providers remained happy getting additional revenue from licensing their existing content.

- Over time, the incumbents realized that they were being disrupted. They saw that Netflix’s growth accelerated the secular decline of cable TV. This prompted many linear TV companies to decide against renewing their agreements with Netflix. But by that time, it was too late. Netflix had become large enough that it had the capabilities to move up the value chain and started creating its own shows.

- In the early and mid-2010s, when the interest rate was low, Netflix funded content investments with debt (more than $10-15 billion per year), a move that was heavily criticized by Wall Street. Netflix’s thinking was that it had the largest user base, so every dollar of content investment would be fixed costs that could be spread over a large user base. With cheap debt, it could continue to prioritize growth over profitability. Over time, it projected its operating margin would increase as its user base grew. Eventually, once the company has positive cash flow, it will rely less on debt.

Today, Netflix has turned the corner and achieved positive cash flow. Meanwhile, incumbent linear TV providers have launched their competing streaming services. However, none are profitable. Comcast’s Peacock lost almost $1 billion in the last quarter of 2022, while Paramount’s streaming service lost $575 million. Similar to Netflix’s strategy years ago, they have to spend a lot of upfront capital to create new shows as they try to grow their subscriber base. To make matters worse, most of these companies rely on debt to fund content creation, which has a much higher servicing cost, given current interest rates. As a result, a wave of consolidation has begun. Last year, Discovery merged with Warner Brothers, creating a new public company that operates MAX (formerly HBO MAX – it’s dropping the HBO brand – it’s all very confusing).

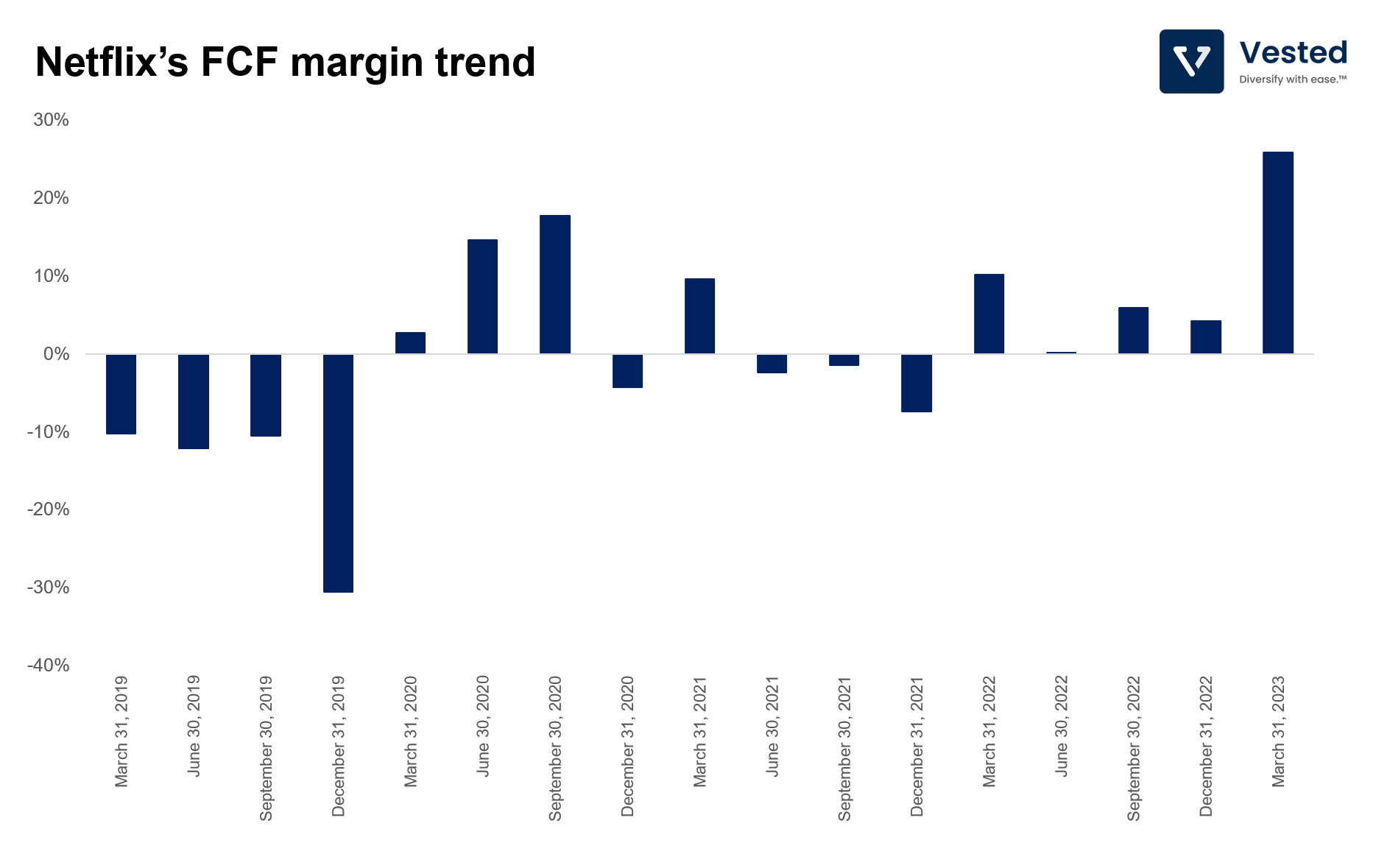

In contrast, after years of binging on debt, Netflix is now meaningfully cash flow positive (Figure 3). In hindsight, some of Netflix’s evolution was extremely smart on the part of management (the early decision to own the content and prioritize scale to get operating leverage). The company also had a bit of luck, with higher interest rates causing cheap debt to no longer be available, just when its competitors need capital the most.

To be fair, though, Netflix’s evolution is not without missteps. For years, it stated that it would never add advertisements and even promoted account sharing. These policies, while good for growth, have been suboptimal for revenue. Netflix estimated that more than 100 million households are consuming Netflix without paying. As the company’s growth sputtered this past year, it has been moving to reverse these two policies to increase monetization. This earnings release helps us understand Netflix’s progress on the reversal.

Advertisements turned out to be a good addition

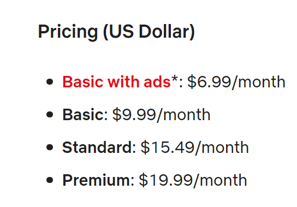

In November 2022, Netflix launched an ad-supported streaming service at $6.99/month, which is $3.00 cheaper than the next tier (Basic, $9.99/month) and $8.50 cheaper than the most popular plan (Standard, $15.49/month). For the ad business to be accretive, the ads must generate between $3.00 – $8.50 per user/month.

From the shareholder letter (emphasis ours):

We are pleased with the current performance and trajectory of our per-member advertising economics. In the US for instance, our ads plan already has a total ARM (subscription + ads) greater than our standard plan. So this month, we’ll upgrade the feature set of our ads plan to include 1080p versus 720p video quality and two concurrent streams in all 12 ads markets – starting with Canada and Spain today. We believe these enhancements will make our offering even more attractive to a broader set of consumers and strengthen engagement for existing and new subscribers to the ads plan.

While Netflix did not divulge the exact additional revenue from the ads, it stated that, in the US and Canada, adding ads generates more revenue than the standard plan. This means that ads generate more than $8.50 per user/month. To put that into perspective, that is more than 4.5x of revenue per user/month that the company can generate in India (from its cheapest plan). Compare this ad revenue rate to that of Hulu. Hulu generates approximately $15 per user/month in ad revenue (on top of the basic $6/month subscription fee). If Netflix can achieve the same monetization rate as Hulu, the revenue per user generated would exceed Netflix’s Premium tier ($19.99/month).

PS: In the US, Hulu is a standalone streaming service. In other countries, it is often bundled with Disney’s streaming service.

This is why Netflix is adding more features to promote ad-tier adoption. This is also potentially why it lowered prices in 116 countries, a move received negatively by the market at the time since it was considered a sign of weakening demand. Lowering prices in emerging markets will increase adoption, allowing Netflix to gain revenue via advertisements instead. Currently, the ad tier is only available in select countries. Considering the top-line contribution observed in the US outlined above, expect Netflix to roll out the ad tier to all markets quickly.

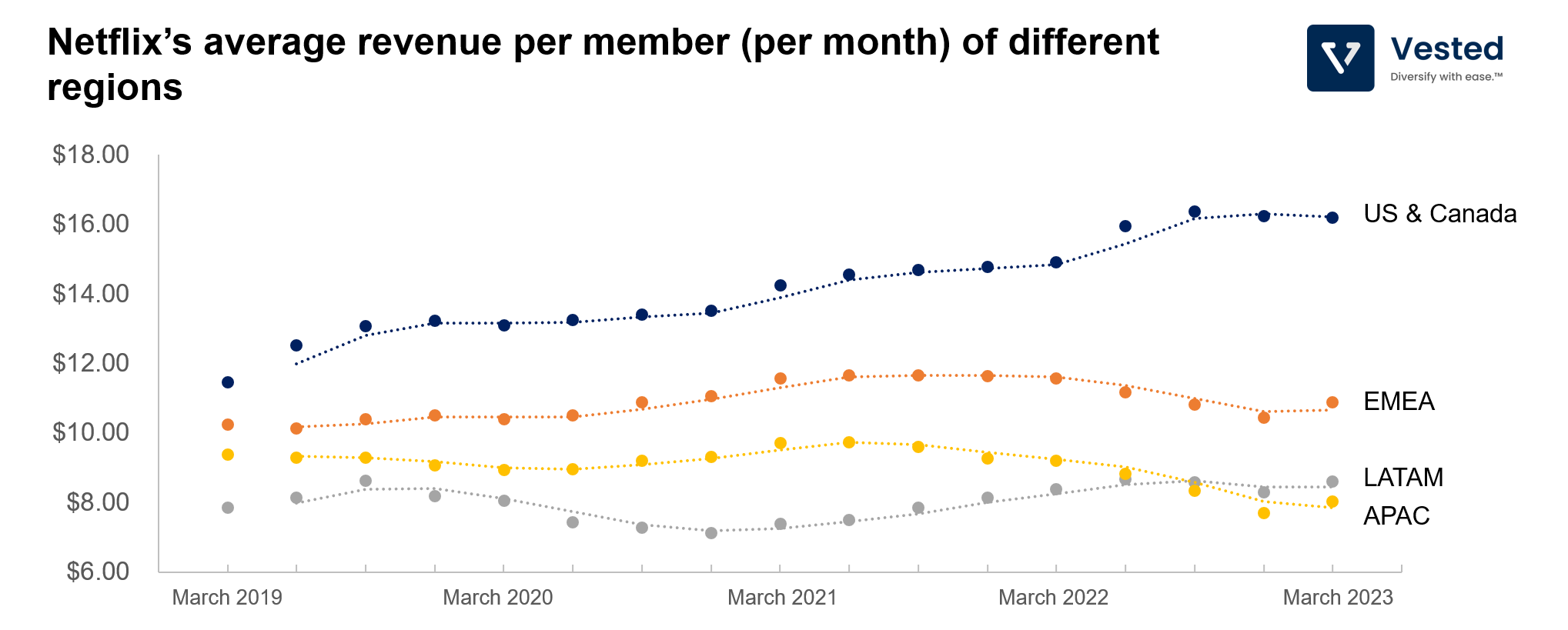

Here’s Netflix’s average revenue per member per month (Figure 5). Revenue in the APAC region has been declining due to the price cuts.

As for account sharing restrictions, Netflix has experimented with the rollout in Latin America and Canada. It observed some short-term decline in member growth, followed by a return to growth as borrowed accounts became paid accounts. In Canada, the account-sharing restrictions have a positive revenue contribution compared to before the restriction on password-sharing.

All in all, ads and password-sharing restrictions are incremental toward revenue and profitability. There are no additional costs incurred, either in marketing or content production, by the company as it clamps down on password sharing. In terms of advertising, traditionally, this has also been a high gross margin business (+80-85%). While management didn’t want to commit to profitability targets for its ads business, it is currently at +50% gross margins, with room to grow. As the rollout continues more broadly, we should expect impacts on Netflix’s top and bottom lines.

Taken together, Netflix, with 230 million global subscribers, is evolving into a lower-cost, ad-supported, increasingly low-brow content destination. Netflix’s old goal was to become HBO before HBO could become Netflix. Instead, Netflix evolved into something else. It evolved into the thing it disrupted. It has become the new TV.