When I was a kid, I hated history lessons. They were always an exercise of memorization of dates, names, and places (“so and so general won a battle in a place long forgotten”). But as an adult, I’ve developed more appreciation towards the subject.

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme” – maybe Mark Twain

Or if you’re a SciFi fan, this one may resonate more with you:

“All this has happened before, and all this will happen again” from Battlestar Galactica (IMO one of the best SciFi out there)

This is because as the pace of change has increased, reaction to these changes often replicates human responses from the past. Human nature adapts much more slowly than the pace of change. As a result, you can look at history to better understand the present and the future.

Newspaper vs. the radio and the internet

Before the internet and the TV, there was the radio.

In October 1938, Orson Welles and his group performed a radio broadcast depicting Martian invasion in New Jersey. The broadcast, adapted from H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds novel, was a news bulletin style story depicting how the US was being laid waste by Martian invaders.

The following morning, major US newspapers chronicled the panic that happened because of the broadcast.

Newspapers across the US depicted how naive Americans experienced mass hysteria thinking that the invasion was real.

“By the next morning … the panic broadcast was front-page news from coast to coast, with reports of traffic accidents, near riots, hordes of panicked people in the streets, all because of a radio play,” – a PBS documentary from 2013

The problem is, none of the hysteria was true. The radio broadcast listenership was so low, that most people never heard of it.

So the question is then: Why did the print industry sensationalize the impact of Welles’ broadcast?

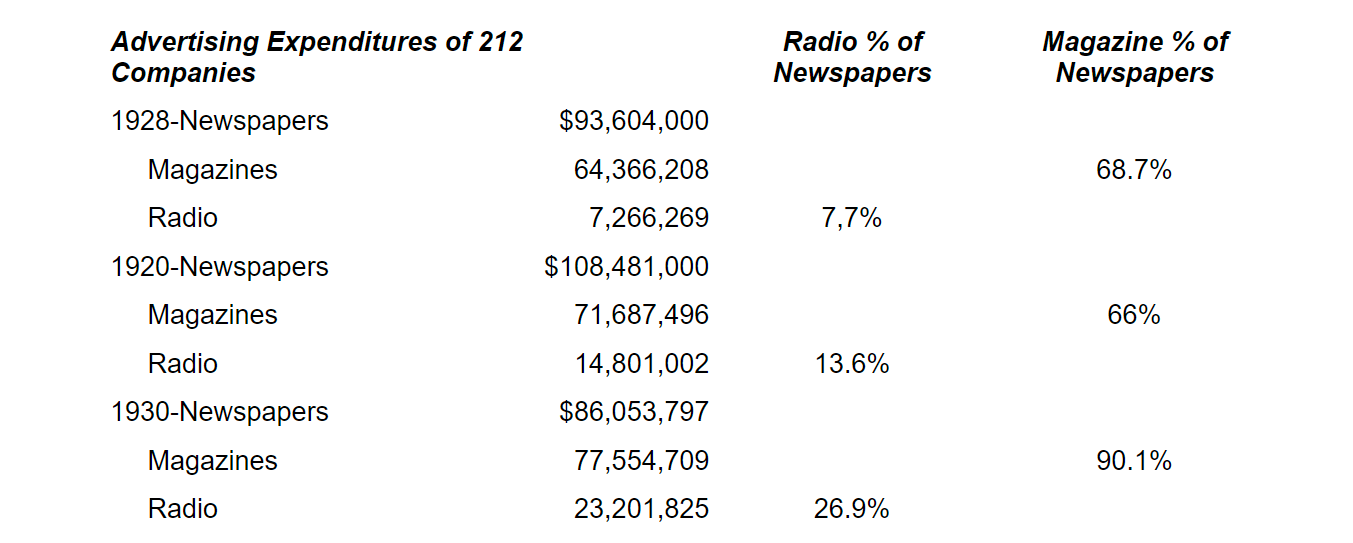

One theory was that it was because of competition. In 1938, the hostility between the print industry and radio broadcast was high. The print media owned news and was doing everything in its power to prevent the upstart radio networks from broadcasting news. This is because newspapers were losing their advertising revenue to the radio (see Figure 1 below for a snapshot data from that era).

What does this have to do with the present?

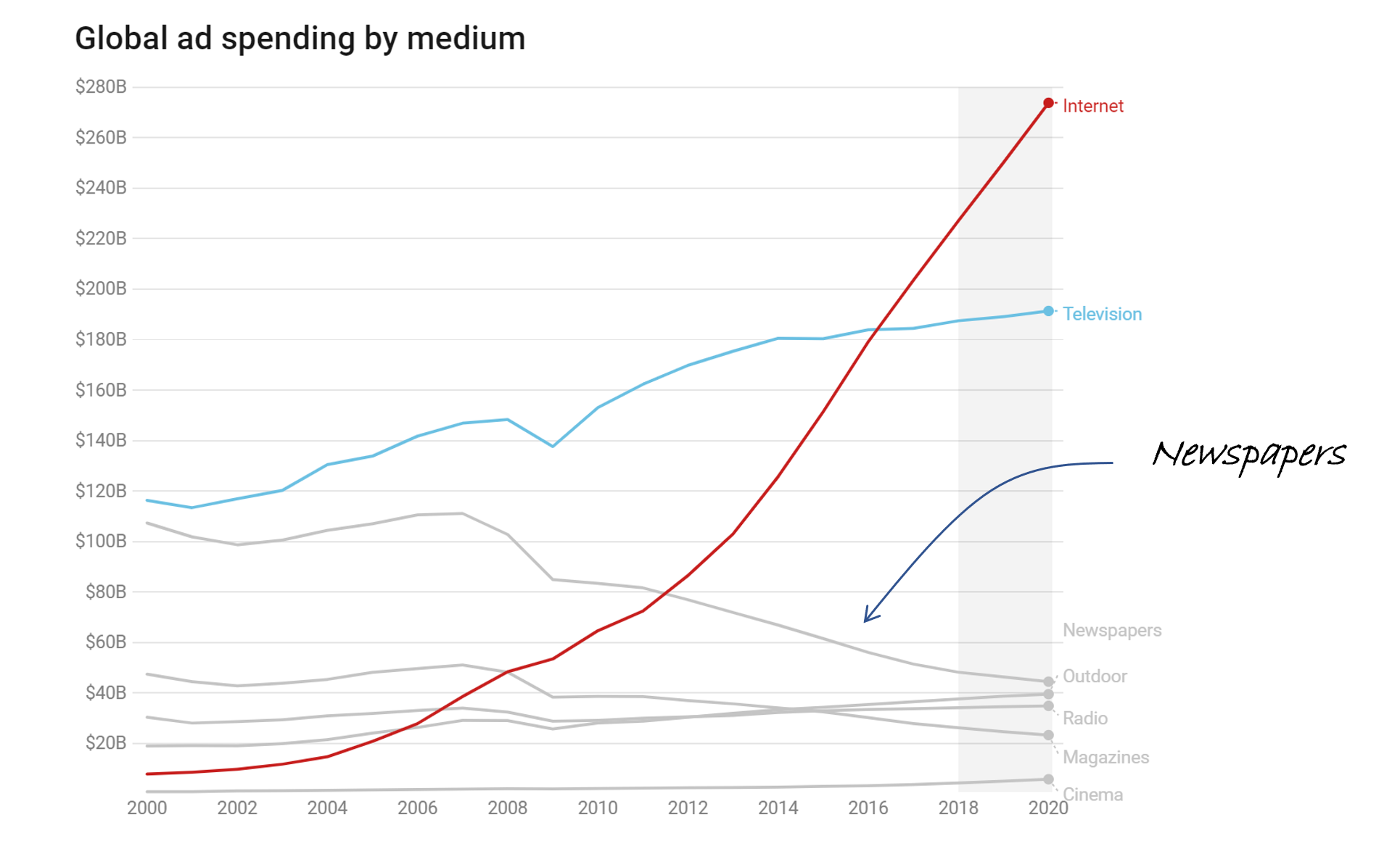

In a previous article, we talked about how Microsoft, who use to be public tech enemy number #1, is now mostly operating without scrutiny (you can find it here: It Pays To Be Number 2 – Microsoft). Facebook and Google are not so lucky. Part of the reason is because they are ad giants that dominate global advertising. Since the turn of the past decade, global ad spend on the internet has exceeded that of newspapers.

It is perhaps with this knowledge that we may view tech coverage by mainstream news outlets differently. See Figure 3 for an example of how New York Times’ coverage of Facebook has changed over the years.

Stablecoins and the free banking era

There was a period in the US where anyone could open a bank at will, without a license or a charter. They could hang a sign in front of their door, start collecting deposits, and give out loans. This period in American history is called the Free-Banking Era (1837 – 1864). The law that enabled this freedom came from the fear of concentration of economic and political power in large financial centers. As a result, there was a desire to increase decentralization (if that sounds familiar – please read on).

By the 1860s, more than 18 US states had adopted the law, including New York and Michigan. Despite the name, Free-Banking does not mean no regulations. It just means that each state was free to set up their own operating principles and minimum capital requirements, and that no permission was required to open a bank.

Another implication of this era was that private entities were allowed to issue their own currencies, called specie, which were typically backed by bonds as collateral.

This era was a particular one in the history of the US because:

- The diversity of money was high. Since many private entities were issuing money, there were a lot of money types. As such, one must be familiar with the bank note to trust it. The further you were from the issuing entity, the less value the money had.

- Lots of fraud. Anyone could issue paper notes. Anyone could call themselves banks.

- Bank failures. The period was marked with a high rate of bank failures. Some of them were due to fraud. But one study suggests that the primary reason was recession. Many of these banks were weak (due to the lack of centralized regulations and common capital requirements). Recession caused people to withdraw their funds, which caused many banks to go under.

If the three bullet points above sound familiar, it’s because we are entering a similar phase in decentralized finance (DeFi). Take stablecoins for example. These are crypto tokens that are pegged to some stable fiat value (typically $1.00 per token). In other words, they are private money, issued by anyone without needing a license or charter. As a result:

- The diversity of stablecoins is high. A quick Google search revealed at least 86 stablecoins.

- Lots of frauds? Tether, the largest stablecoin issuer, may not have the assets to back the currency in circulation.

- Issuer failures. As inflation tickets higher, interest rates go up, and financial markets are becoming less stable, some of these stablecoins start failing. One issuer of stablecoins, Terra, failed. Another, pseudo bank, Celsius, a DeFi bank that promised 18% interest rates for locking up your crypto, has frozen withdrawals to prevent a bank run.

Let’s dig deeper into Terra’s collapse. As we mentioned above, Terra is an issuers of a stablecoin pegged to the USD. There are different types of stablecoins:

- Fiat-backed: They hold fiat currency dollar per dollar of issued stablecoins. Tether, USDC, and Pax Dollar fall under this category.

- Crypto-backed: They are backed by other crypto currencies (typically Ethereum). But because of the volatility of crypto generally, the amount of collateral typically is 50% to 100% higher than the issued stablecoins.

- Commodity-backed: As the name suggests, these are backed by physical assets: precious metals, oil, or even real estate.

- Algorithmic: These use decentralized rule-based algorithms to maintain a stable value (what could go wrong?). TerraUSD falls under this category.

Terra is an algorithmic stablecoin. Here’s a great explainer from Bloomberg on how TerraUSD works (emphasis ours):

“An “algorithmic stablecoin” sounds complicated, and there are a lot of people with incentives to pretend that it is complicated, but it is not. Here is how an algorithmic stablecoin works:

- You wake up one morning and invent two crypto tokens.

- One of them is the stablecoin, which I will call “Terra,” for reasons that will become apparent.

- The other one is not the stablecoin. I will call it “Luna.”

- To be clear, they are both just things you made up, just numbers on a ledger. (Probably the ledger is maintained on a decentralized blockchain, though in theory you could do this on your computer in Excel.)

- You try to find people to buy them.

- Luna will trade at some price determined by supply and demand. If you make it up on your computer and keep the list in Excel and smirk when you tell people about this, that price will be zero, and none of this will work.

- But if you do a good job of marketing Luna, that price will not be zero. If the price is not zero then you’re in business.

- You promise that people can always exchange one Terra for $1 worth of Luna. If Luna trades at $0.10, then one Terra will get you 10 Luna. If Luna trades at $20, then one Terra will get you 0.05 Luna. Doesn’t matter. The price of Luna is arbitrary, but one Terra always gets you $1 worth of Luna. (And vice versa: People can always exchange $1 worth of Luna for one Terra.)

- You set up an automated smart contract — the “algorithm” in “algorithmic stablecoin” — to let people exchange their Terras for Lunas and Lunas for Terras.

- Terra should trade at $1. If it trades above $1, people — arbitrageurs — can buy $1 worth of Luna for $1 and exchange them for one Terra worth more than a dollar, for an instant profit. If it trades below $1, people can buy one Terra for less than a dollar and exchange it for $1 worth of Luna, for an instant profit. These arbitrage trades push the price of Terra back to $1 if it ever goes higher or lower.

- The price of Luna will fluctuate. Over time, as trust in this ecosystem grows, it will probably mostly go up. But that is not essential to the stablecoin concept. As long as Luna robustly has a non-zero value, you can exchange one Terra for some quantity of Luna that is worth $1, which means Terra should be worth $1, which means that its value should be stable.

All of this is, I think, quite straightforward and correct, except for Point 7, which is insane. If you overcome that — if you can find a way to make Luna worth some nonzero amount of money — then everything works fine.”

Easy enough, what could go wrong?

As the Bloomberg article pointed out. Step (7) is the problem. Since it’s not based on real cash flow generated from selling goods and services (transaction fees within the blockchain system do not count), when faith in the system is lost, people will start selling. When that happens, the selling won’t stop, the prices of Luna goes down, and eventually, supply of Luna would be depleted. So they would have to print more. Luna prices fall further. And you enter a death spiral.

In fact, this is what happened, wiping out more than $60 billion in capital, and in South Korea alone, impacting 280,000 citizens.

Of course, the death spiral described above is not new. Issuing volatile currency to maintain a peg against another more stable currency is not novel to Luna/Terra. In fact, this is commonly done by countries. And as history has taught us, pegging currencies against the US dollar, without being backed by a strong balance sheet, can lead to disastrous results. History is littered with countries that tried to maintain its USD peg by issuing more local currencies, which forced them into a death spiral, when the peg broke.

In 1994, Mexico failed to maintain its USD/Peso peg, and experienced 52% inflation. In 1997, Thailand’s Baht collapsed after the country failed to maintain its USD peg in the face of overwhelming capital outflow. This triggered the 1998 South East Asia economic crisis and resulted in significant devaluation of the region’s currencies.

So clearly, the Luna/Terra debacle is preventable had they learned from history. As of this writing, TerraUSD (called the TerraCLassicUSD) is trading at $0.01587 per token.