Netflix Content Acquisition Strategy (part 2)

This is part 2 of our in depth analysis of Netflix’s content acquisition strategy. Read here for part 1

After beating analysts’ growth estimate for Q3 2018, Netflix’s share price soared. The share price has since decreased by more than 12% in the week after the earnings release however. Investors are worried of Netflix’s increasing debt load, which the company needs to continue to fund new content creation.

Funding Netflix’s growth:

Figure 1: Growth of Netflix’s Long term debt and Interest expense.

To fund its aggressive growth, Netflix has relied heavily on long term, high yield debt. As of end of Q3 2018, long term debt is at $8.4 billion, with $17.7 billion in streaming content obligations. As its debt load grows, Netflix is spending more to service its debt (pay interest and principle of the debt). In 2017, it spent $238 million in interest expenses. This number is up to $182.3 million for the first half of this year, on track to exceed $300 million in 2018.

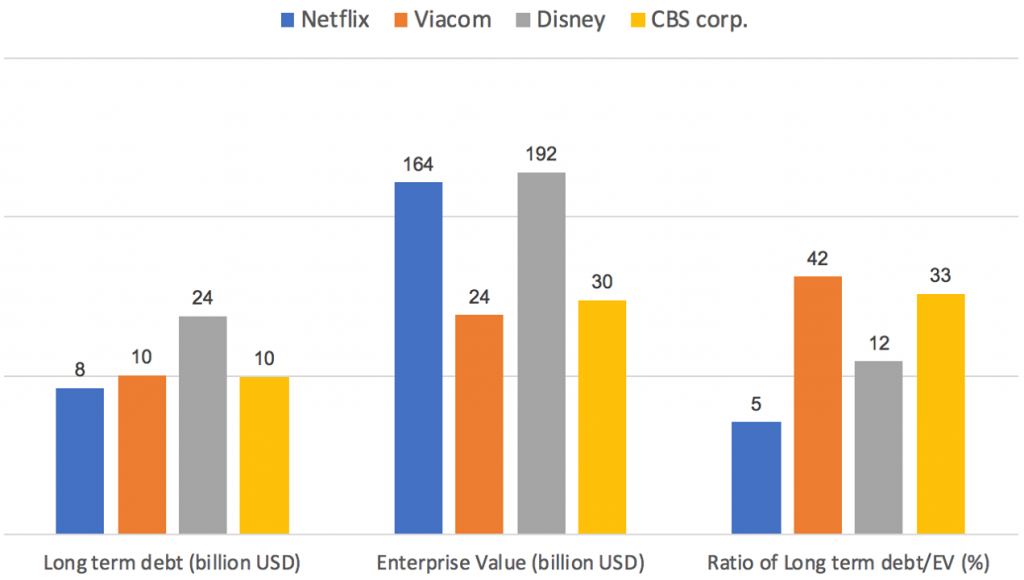

Nevertheless, Netflix plans to operate in the negative free cash flow regime in the foreseeable future, as upfront capital is necessary due to the lag between content investment and revenue realization. Furthermore, it will continue to finance its capital needs via debt, since its after-tax cost of debt is lower than its cost of equity, with a debt to enterprise value ratio of 5%, Netflix’s debt to enterprise value ratio is lowest compared to its chief US competitors (Viacom, Disney, and CBS corp.), see Figure 2. The risk with this debt-fuelled growth is that rising interest rates in the US will increase Netflix’s borrowing costs to fund new content creation (Netflix needs to borrow an additional $5 billion over the next two years for new content creation), but this risk is true for everyone in the industry.

Figure 2: Despite its high long term debt burden, Netflix’s ratio of Debt/Enterprise Value is lowest compared to its competitors.

Competitive Reaction:

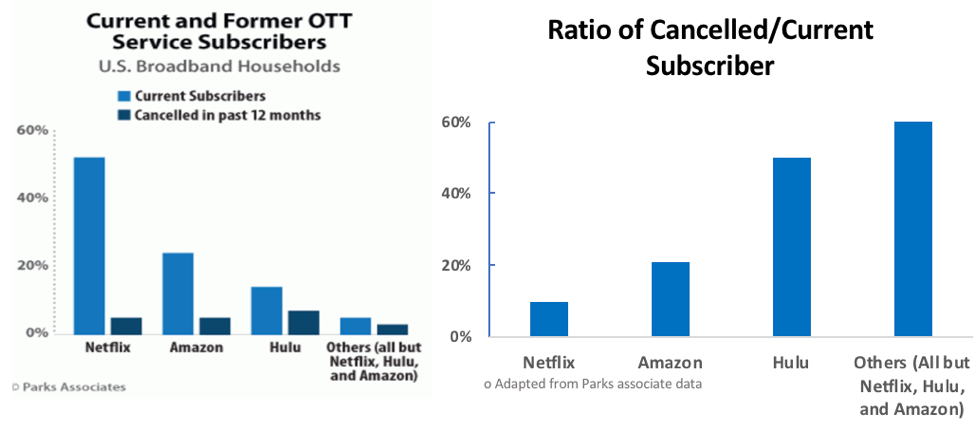

In the threat of Netflix global dominance, its competitors have started pulling content and discontinuing licensing agreements. After its initial licensing deal with Netflix expired, Starz refused to sign a second deal despite being offered $300 million, a 10X increase of the original agreement. Starz proceeded to start its own streaming service in October 2012. Similarly, Showtime, HBO, and CBS have started their own streaming services as well. Currently, these services represent a small fraction of the streaming market, less than 5%.

Netflix’s two largest OTT competitors currently are Hulu and Amazon. Hulu, which is owned by Comcast, started off as a service that targets cord cutters, showing exclusively time delayed 2nd run content from the traditional content providers. Hulu did not invest in original programming until 2012. Even then, it was mostly small investments in reality, web-news type shows. Only in 2015 — 2016 did Hulu start releasing original content that is similar in quality to linear TV shows. Even now, its current offering is nowhere near to that of Netflix.

Amazon, on the other hand, presents a unique challenge to Netflix. Since Amazon is an ecommerce platform, its approach to original content creation is an orthogonal one. That is, Amazon creates a library of original content as a way to attract and retain prime members. As such, Amazon can afford to invest heavily in content since the revenue drivers are prime membership plus online spending, which is nearly double for prime when compared to non-prime customers ($1300 for prime vs $700 for non-prime). But perhaps due to the orthogonal nature of Amazon’s approach, there will be room for two streaming services in an average consumer’s monthly expenditures: streaming budget for Netflix, and shopping membership with Amazon prime — prime video is a bonus. Nonetheless, competitive pressure from Amazon likely will have a significant effect on the supply of content — pushing prices up for original content.

One final competitor worth discussing here is Disney. After its agreement with Starz ended in 2012, Netflix signed an exclusive streaming deal with Disney to stream theatrical releases in the same window as premium cable channels, a deal that took into effect in 2016. In August 2017, however, Disney announced that it will not extend the agreement beyond 2019. Instead, it will launch its own streaming service, leveraging its $1.58 billion investment in BAMTech, a Major League Baseball (MLB) founded video streaming provider. And now, after its acquisition of 21st Century FOX, Disney is one of the largest differentiated content owner (with franchises that includes Marvel, Star Wars, and its own Disney Pixar), thus when the service is launched, it will pose a significant challenge to Netflix.

It will be interesting to see what content strategy Disney’s steaming service will take. Will it focus on children’s shows? Will it leverage its Marvel and Star Wars content? Or both? Whatever it is, it will be a very compelling content package for any audience. The wrinkle here is that, although poised to be very competitive with Netflix, it will also be detrimental to Disney’s largest source of revenue: TV cable companies, as this move will only accelerate the secular decline of linear TV.

As a response to Disney’s move, Netflix made its first ever acquisition. It acquired Millarworld, a comic book company with popular IPs such as Kingsman and Kick Ass. This acquisition is to acquire exclusive IPs to replenish the soon to be pulled Marvel TV content that is highly popular, as Disney owns Marvel.

Conclusion:

Netflix has no choice but to spend aggressively on content, even if it costs more than a quarter of a billion dollar annually to service these debts. Let’s compare Netflix to its FAANG brethren, Facebook. Similar to Netflix, Facebook is a super aggregator. Facebook owns the customer relationship and monetizes users’ engagement through advertising. Unlike Netflix however, Facebook users return to the service for their own generated content — their own social data. Therefore, Facebook has little dependency towards external media companies and can extract the bulk of the profit. On the other hand, Netflix users return to the service to consume non-user generated content (movies, comedy stand ups, TV shows). Therefore, if Netflix does not create its own original content, it will be at the mercy of its content providers.

Netflix needs to reduce dependency on other content providers, by creating differentiated exclusive programming; and it has to do this fast, before its library is depleted by its competitors. This explains the aggressiveness of the debt-fueled investment in content this past several years. This urgency is essential especially considering the 1–3 years delay between investment and release of content. Thus far, it seems that this strategy is working. Netflix is not only growing its user base, but growing it at an accelerated rate.

[mc4wp_form id=”1064″]

Thanks for reading!