Given the importance of this week’s topic, we decided to remove the paywall and make it available to all. If you like deep dives like these, please support us and subscribe to our Premium plan to receive more. After all, it only costs the equivalent of two Americanos from Starbucks.

PS: Did you know? Starbucks has such a strong franchise value that it can charge roughly the same amount for its products globally. A tall Americano in the US costs $2.25 before tax. In Mumbai, it’s the equivalent of $2.65, and in Jakarta, it is $2.23. This is quite a feat, especially considering that the cost of purchase power parity between the US, India, and Indonesia is quite large.

Before we begin, for investors that invest through Vested, we want to reiterate that your funds are not impacted by recent events and are safe. Deposits to your Vested Invest account have no exposure to SVB – they are received by JP Morgan and are held in custody at Customers Bank. Furthermore, your account continues to be insured for up to $500k by SIPC and up to $250k by FDIC.

Note: If you have an active Vested Premium Plan, you should be able to access any premium newsletter content.

Why banks fail

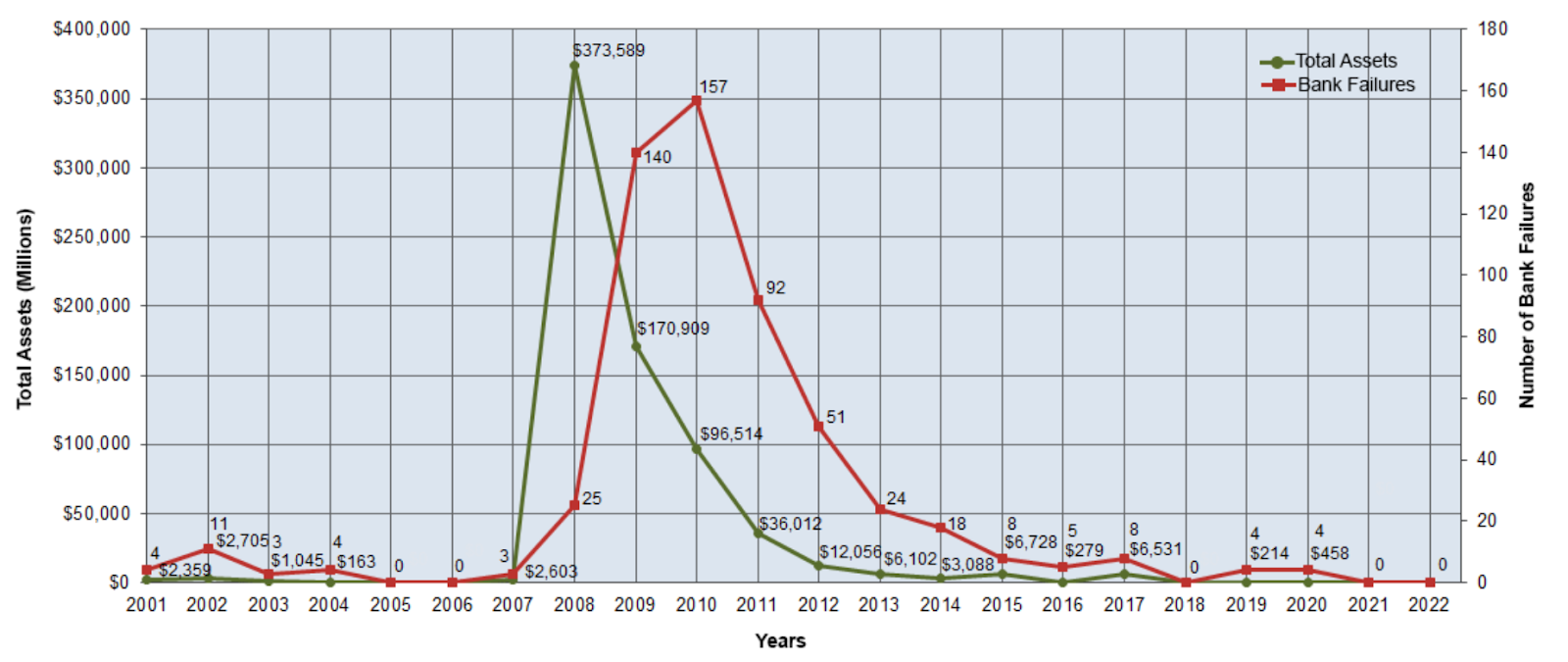

Banks in the US do not fail that often. Between 2001 – 2022, there were 561 bank failures. 83% of these occurred during the great financial crisis (GFC) between 2008 – 2012. In most years, the number of bank failures has been below 10 (a small number considering there are more than 4,500 FDIC-insured banks in existence today). In both 2021 and 2022, no banks failed.

So, it is with great surprise that three banks have failed in the past week: Silvergate Bank, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), and Signature Bank. All three are relatively large banks that specialize in specific industries. In the case of Silvergate and Signature, it was the crypto industry. In the case of SVB, it was the venture and startup community.

Both banks failed due to different reasons but followed the same mechanism:

- They received a large deposit influx between 2020 – 2021

- They invested in high-quality securities

- The Fed increased rates at an unprecedented level, exposing banks to duration risks

- Banks with customers that were highly concentrated in specific verticals failed

Phase 1: Get a large influx of deposits

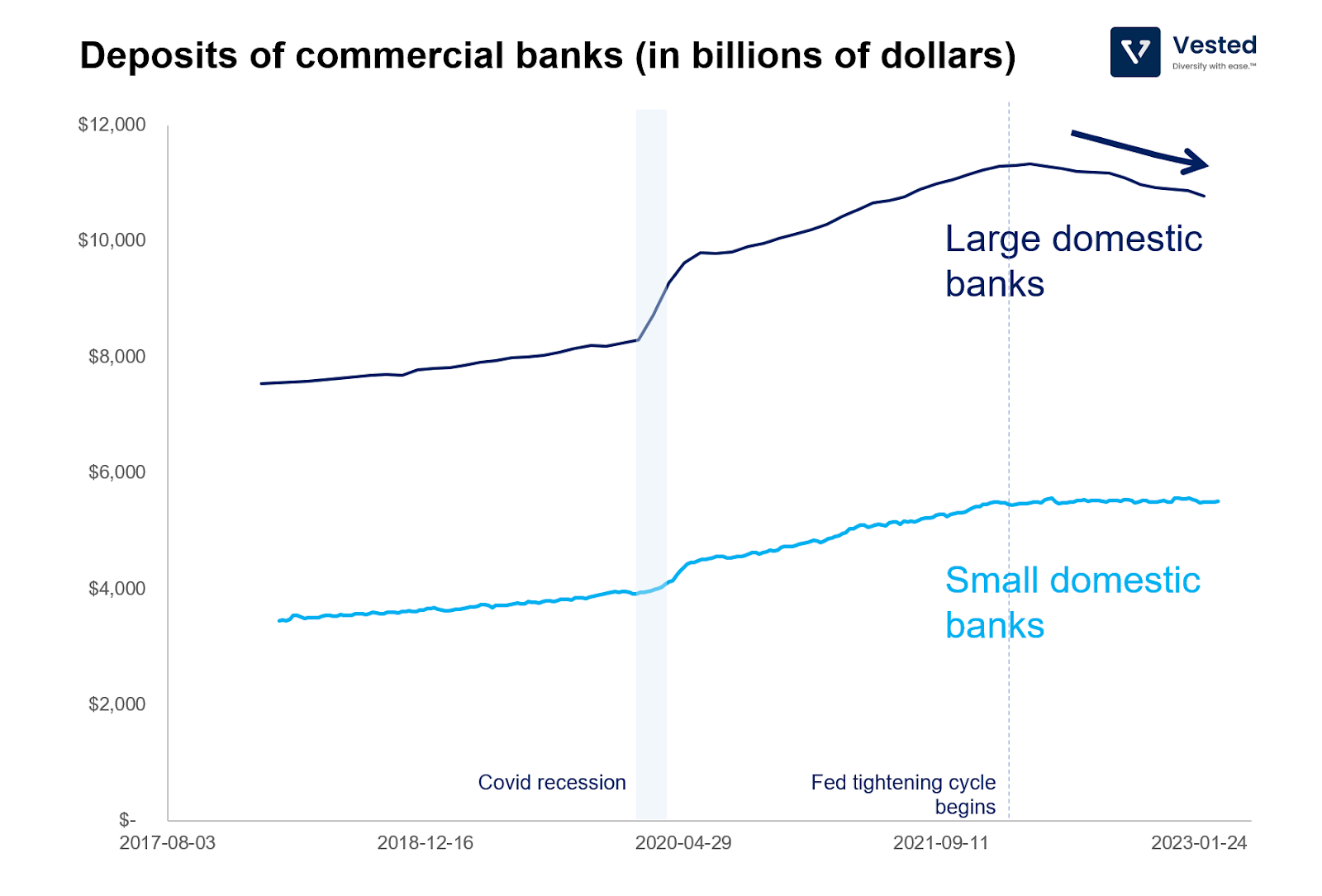

During the 2020 – 2021 easy money era, the negative interest rate environment and the government stimulus flooded the economy with excess cash, which got deposited into bank accounts. Figure 2 below shows the deposit trends (in billions of dollars).

Both small and large banks saw a large increase in the deposit rate. Between Q4 2019 and Q1 2022, deposits at US banks rose by $5.4 trillion. This is problematic for banks because they have to do something with these deposits. In an environment with so much excess cash, no one wanted to borrow money, so the demand for loans was weak. According to JP Morgan research, during this period, only ~15% of deposits were lent out.

Phase 2: You can still get in trouble despite investing in high-quality securities

The banks then invested some of these deposits in high-quality debt instruments (after all, they learned from the great financial crisis a decade ago), typically bonds (US Treasury bonds, mortgage-backed securities, etc.).

How much gets lent out and how much the banks keep for rainy days is governed by a complex set of rules. The simplest way to think about a bank is if you give it $1.00, they can lend/invest $0.90 of this (this translates to a 10% reserve ratio). The $0.90 invested becomes a deposit for someone else in another bank account, where a similar ratio is at play, further multiplying the amount of money in circulation. This is how money multiplies and is the heart of the fractional banking system.

The ratio of how much is kept vs. how much is lent out/invested varies for different banks and at various periods. The central bank can alter this ratio to promote/contract the money supply.

Phase 3: Rapid interest rate hikes

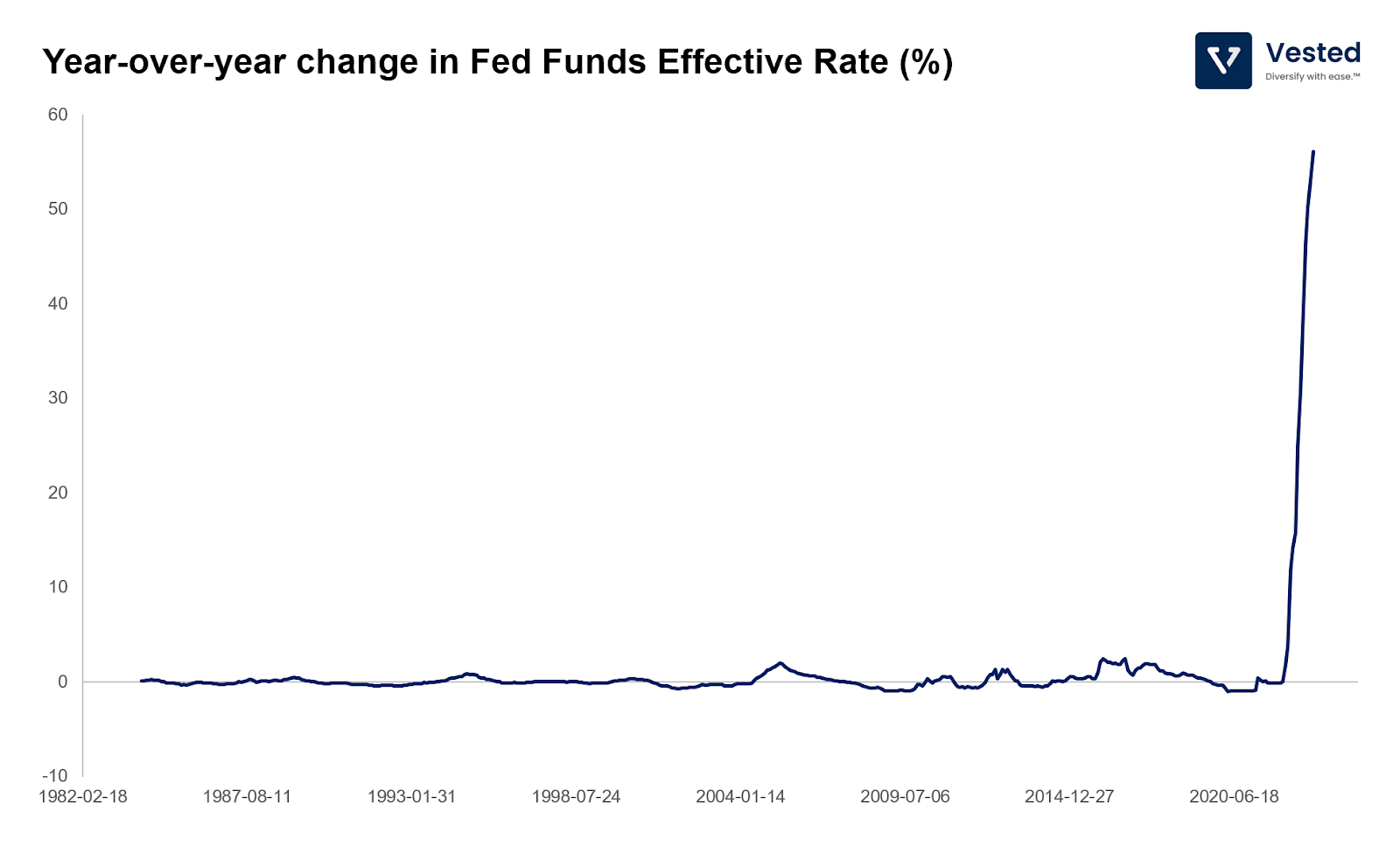

Under most circumstances, investing in high-quality securities is a great strategy. But we are not currently living under normal circumstances. In the past year, the Fed increased interest rates faster than at any time in more than 40 years after months of saying that it wouldn’t do so.

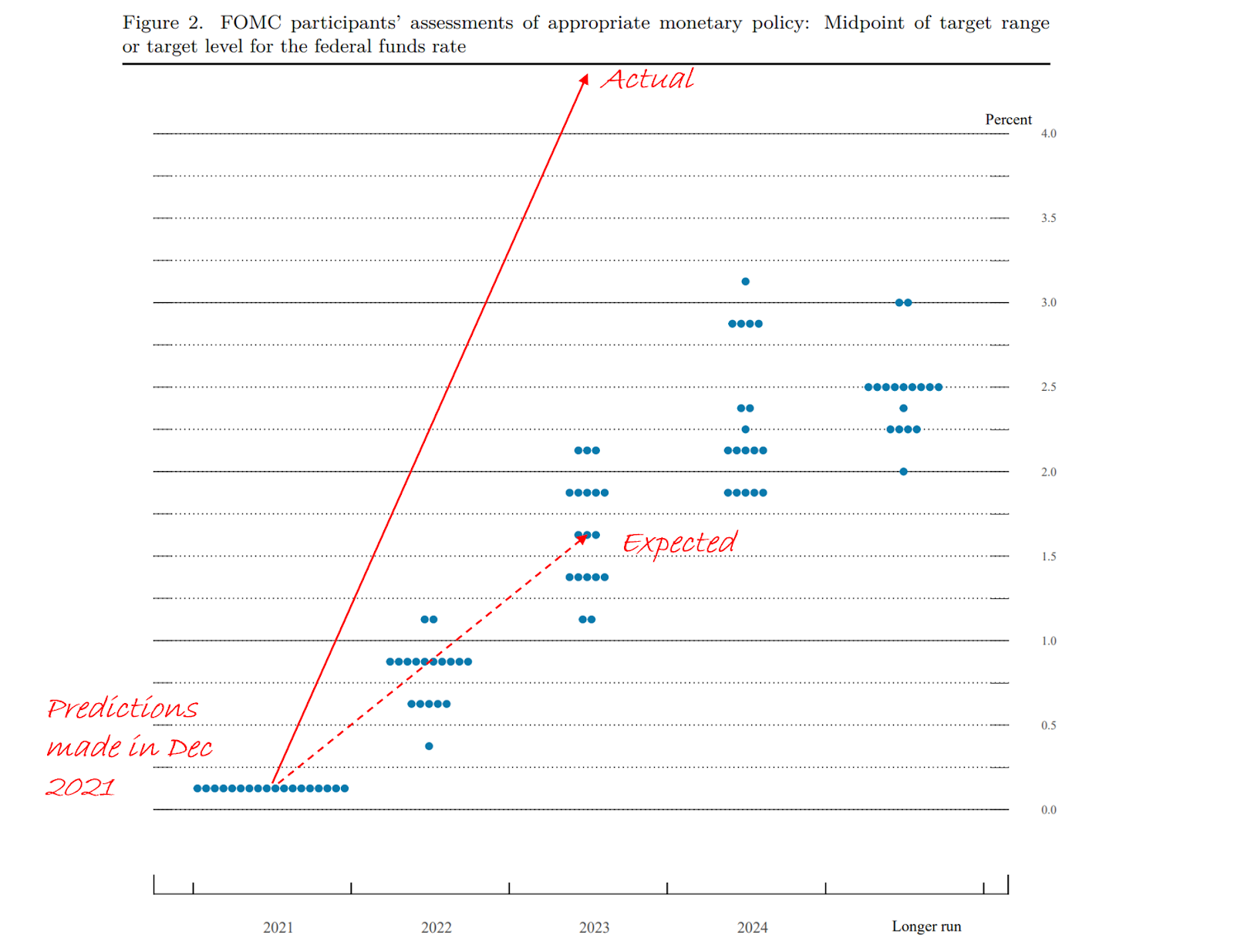

For the better part of 2021, the Fed believed inflation was transitory (a temporary anomaly due to supply chain disruptions). Here are the projections they released in December 2021.

Their projections were way off. In December 2021, they expected the 2023 rate to be 1 – 2%. As of February 2023, the Fed Funds rate was 4.57%, much higher than the 0.08% in February 2022. This represented a 5600% increase (that’s not a typo).

Inflation was proven not to be transitory, so the Fed changed its stance quickly, as they were deeply concerned with inflation. To prevent inflation expectations from being entrenched, they were very aggressive with interest rate hikes.

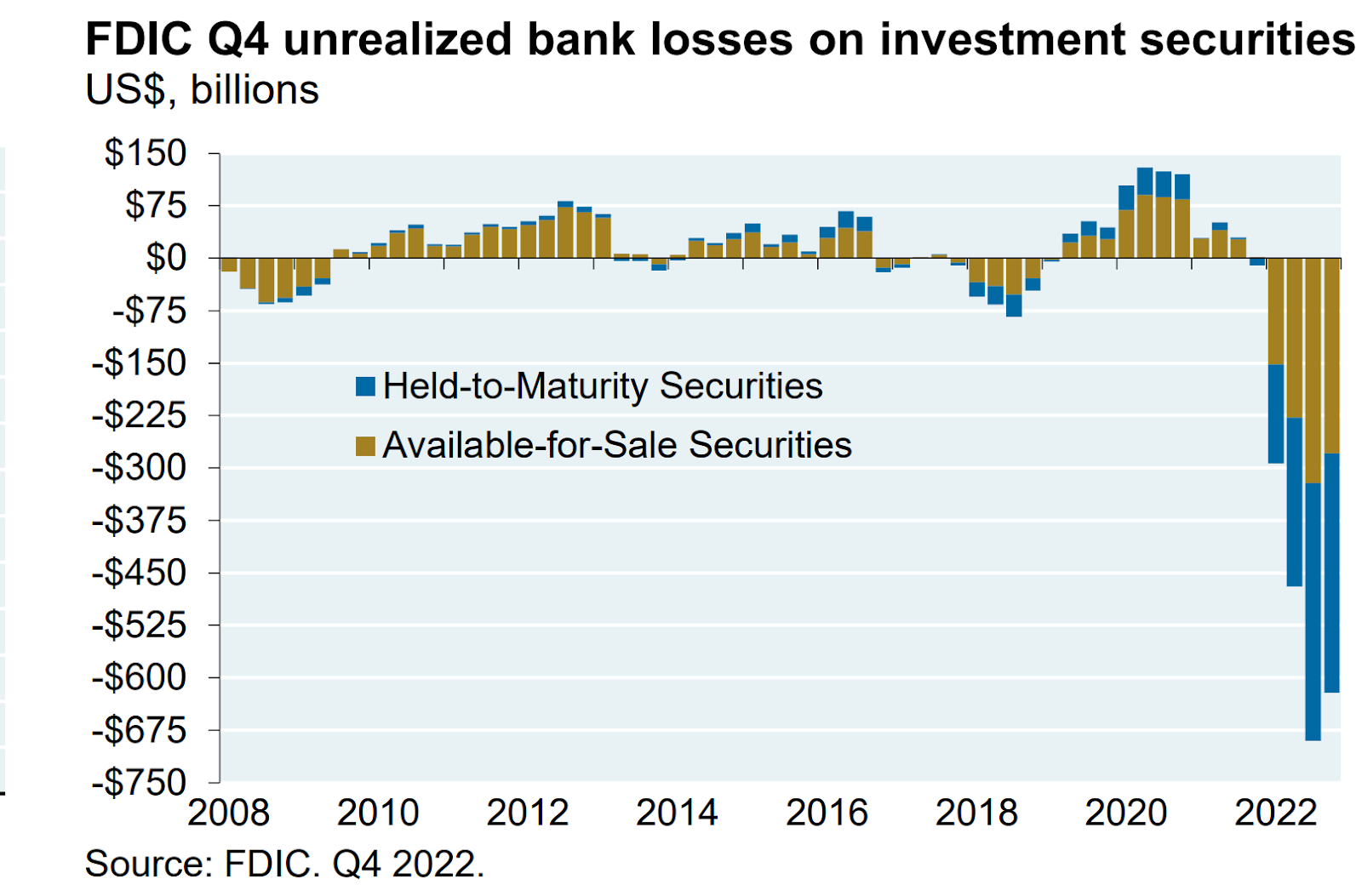

The problem was that banks made lending and investment decisions based on the Fed’s projections. Many decided to invest in securities based on the low-interest rates of 2020 and 2021 when cash inflow was very high. These investments are now largely underwater (see Figure 5).

There are a lot of complexities involved with accounting for these losses. When banks purchase securities, they have to decide whether they want to:

- Make the asset “available-for-sale” (or AFS). This classification offers more flexibility as they can be resold and hedged against interest rate risks. However, AFS unrealized losses pass through the income statement

- “Hold-to-maturity” (or HTM). In the US, this classification has the benefit of no mark-to-market requirement, which means that unrealized losses would not flow through the income statement. But for HTM securities, you cannot hedge against interest rate fluctuations. This became an important factor in SVB’s downfall

Different banks have different strategies for the above selection. And as we discovered only after the fact, the strategy choice greatly matters. More on this later.

PS: A colleague informed me that the accounting for HTM assets in India differs from that of the US. In India, banks have to mark-to-market HTM securities, making unrealized losses easier to observe.

Phase 4: Run on the bank

Recall that in Phase 2, the reserve requirement is always less than 100%. This means all banks (no matter how big or small) do not have cash reserves to meet withdrawal requests at any given time. If the request for cash withdrawal increases at a rapid clip. The bank must replenish cash reserve by:

- Getting more deposits. Unfortunately, the cash deposit rate decreased in 2022, especially for large banks, as shown in Figure 2 above. For Silvergate, Signature, and SVB, the crypto winter and tech downturn have put downward pressure on the cash deposit rate

- Selling off their investments to acquire more cash. This would make those unrealized losses real.

As you can see, this is why a run on the bank is so dangerous. It can kill even the healthiest of banks. But a run on the bank does not happen very often (the last one was more than a decade ago during the GFC). This time, conditions described in Phases 1 – 3 set the stage. Then, Phase 4 happened to the three banks.

Generally, most banks have diverse sets of consumers, either retail or businesses, from different segments of the economy. This helps insulate the bank from (i) an economic downturn that puts pressure on deposit inflow and (ii) a higher chance of a run on the bank due to serving a tight community of users. One common trait that these three banks have is that they have a high concentration of depositors from one segment of the economy.

Silvergate, SVB, and Signature collapsed

On Wednesday, March 8th, 2023, Silvergate wound down operations. The bank, one of two primary banks that work with crypto companies, saw a massive decrease in its deposit base, from $11.9 billion to $3.8 billion in the last quarter of 2022.

On the same day, SVB announced that it would raise money by selling stocks to raise cash. It also planned to sell most of the securities it could sell (realizing the losses). The stock plunged. This in itself is not problematic. While this would hurt short-term profitability for the bank, selling the lower-yield securities would allow SVB to purchase ones that were of higher yield, churning its portfolio (it was pulling the band-aid).

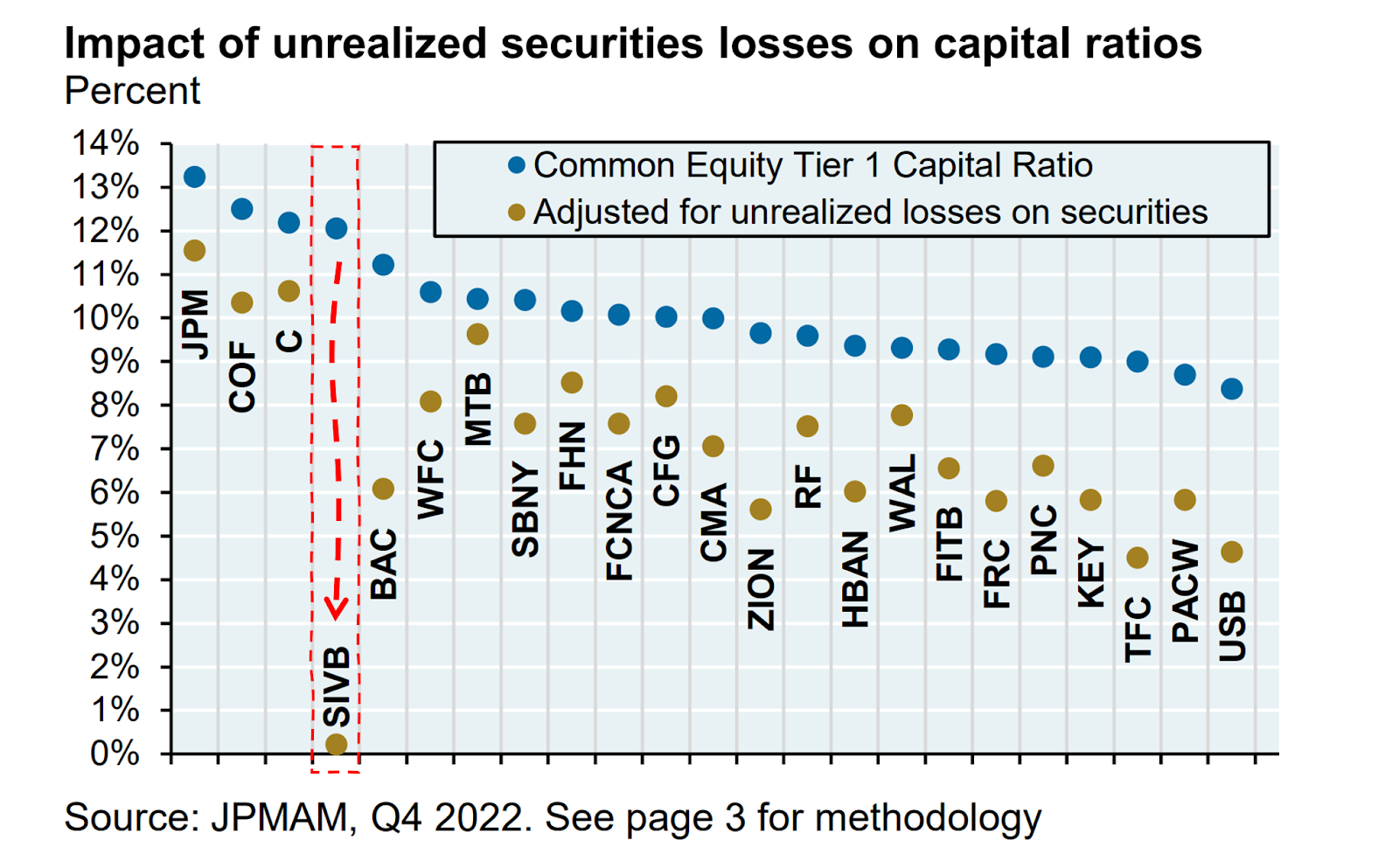

That said, SVB’s investment management was particularly bad. They were overexposed to duration risk compared to other banks (see Figure 6 below). The ratios in this chart represent robustness against stress events. The higher, the better. Blue is the required ratio. Yellow is the theoretical ratio if all unrealized losses were made real (lower is worse). Notice how SVB was very exposed to duration mismatch. It invested over $99 billion, or almost half of its deposits, in long-term HTM securities, now yielding lower than the prevailing Fed rate.

On Thursday, March 9th, 2023, Greg Becker, the CEO of SVB at the time, had a call with its customers, the top VCs, and told them to “stay calm.”

PS: As someone with experience getting into debates with others, typically, uttering the words “stay calm” garners the opposite effect.

As you would expect, the opposite outcome happened. Because SVB caters to many startups, tech companies, biotech companies, and VCs (a tight-knit community), news spread fast, and a bank run ensued. Within the day, SVB saw over $41 billion in outflow, roughly 20% of its total deposits. This is arguably the first bank run in the digital age. Information spread rapidly via social media. Withdrawals occurred quickly via the internet.

On Friday, March 10th, 2023, spooked by the Silvergate and SVB news, Signature, the other Crypto friendly bank, after experiencing a deposit decline due to the crypto winter, saw $10 billion in outflow. Now, word on the street is that despite the significant outflow, the bank was fine. However, it was shut down by NY regulators because “The bank failed to provide reliable and consistent data, creating a significant crisis of confidence in the bank’s leadership”. Perhaps regulators took this opportunity to shut down the last major fiat/crypto ramp.

By Friday morning, March 10th, 2023, regulators stepped in.

Over the weekend, regulators convened. They decided to close both SVB and Signature Bank while guaranteeing all deposits in those banks, even for amounts beyond the $250,000 FDIC insurance limit. This has the equivalent effect of implicitly guaranteeing any deposit amount in any bank in the US.

In addition, the Fed would also give out loans to banks that would need it, in which they would offer loans to banks that pledge their securities as collateral, effectively preventing those banks from needing to sell them at a loss (effectively nullifying the issue shown in Figure 5 and 6 above).

Ultimately, this is a strong stance from the regulators to prevent further contagion.

What happens next?

To the banks

While the government decided not to bail out any of the banks mentioned above, there are ongoing discussions on potential acquisitions of what remains of SVB.

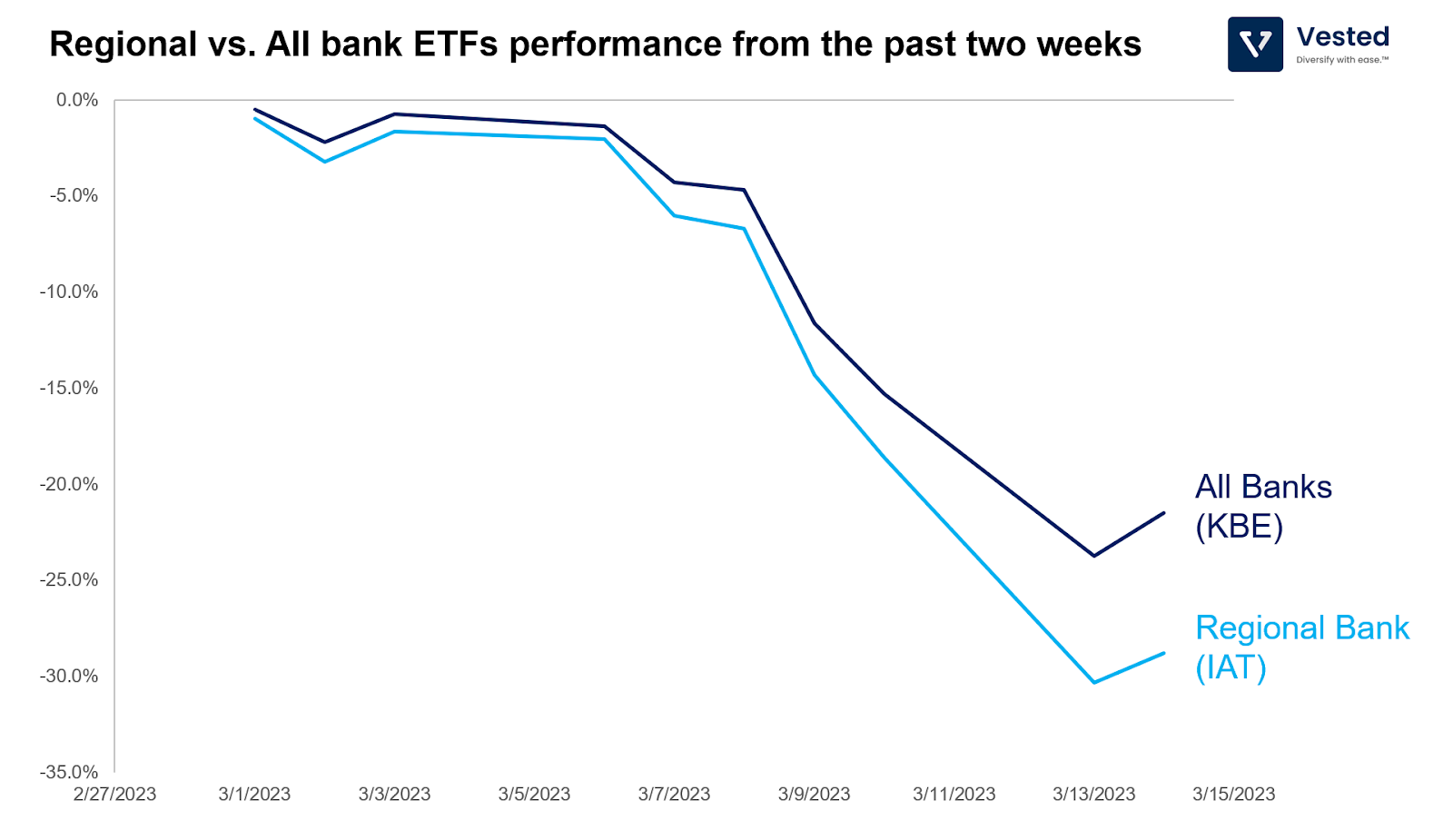

After looking at the data and sequence of events, it does not seem that the smallness of the bank was the problem. Sure, SVB was a regional bank, but they were, before the collapse, the 16th largest bank in the US. In fact, if you look at Figure 2, the deposit rate decline was experienced mostly by the larger banks. Regardless, the share prices of regional banks seem to be more impacted by these events (see Figure 7 below). As of this writing, the share prices of these regional banks are rallying.

To interest rates

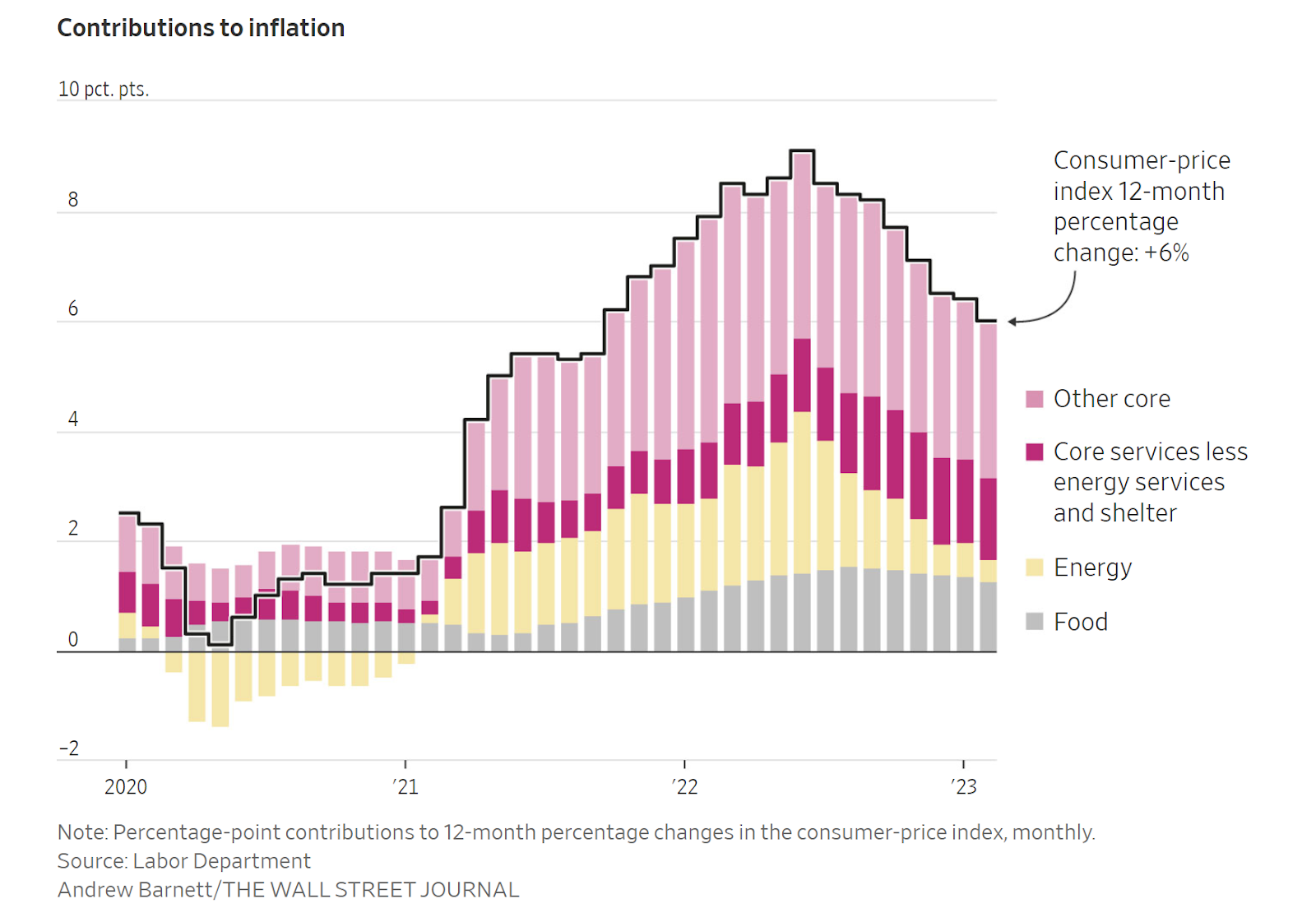

Some in the market believe that this episode will cause the Fed to stop the interest rate hike, especially in light of fresh inflation data that shows inflation at +6% (with core at +5.5%), the slowest increase since September 2021.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoy this piece, feel free to forward this to a friend.