In this blog, we discuss the reversal of globalization and its impact on investing. To help investors adapt to this new trend, we are launching a new Vest (model portfolio): the Deglobalization Vest.

Figure 1 shows the hypothetical historical return of this strategy. The dark blue line represents the Vest performance.

- Over the past five years, it has underperformed in the S&P 500 (left panel in Figure 1 above). This is because, in the second half of the previous decade, low-interest rates propelled returns of mega-cap tech stocks.

- However, higher inflations and geopolitical instabilities have ushered in a new era of investing, which we will discuss in greater detail in this post. The Deglobalization Vest is designed to take better advantage of this era. As such, it performed better than the S&P 500 in more recent periods (1-year and 3-months). See the middle and right panels in Figure 1 (note: past performance is not an indication of future results, and the index performance for any Vest is subject to fluctuation depending on shifting market conditions).

Read on for more details on this strategy.

A changing world paradigm

In March 2000, President Clinton announced legislation that would establish permanent trade relations with China that would bring the country into the WTO.

“China is not simply agreeing to import more of our products; it is agreeing to import one of democracy’s most cherished values: economic freedom. The more China liberalizes its economy, the more fully it will liberate the potential of its people — their initiative, their imagination, their remarkable spirit of enterprise. And when individuals have the power, not just to dream but to realize their dreams, they will demand a greater say.” — Bill Clinton in 2000

This speech has been proven wrong. Open trade didn’t culminate in an open democratic China. In fact, in the past few years, China has taken steps to reverse its open market policies. Regardless, this speech was notable because it marked the beginning of China’s ascent to become the world’s largest exporter, another milestone in a long-term trend of increased globalization.

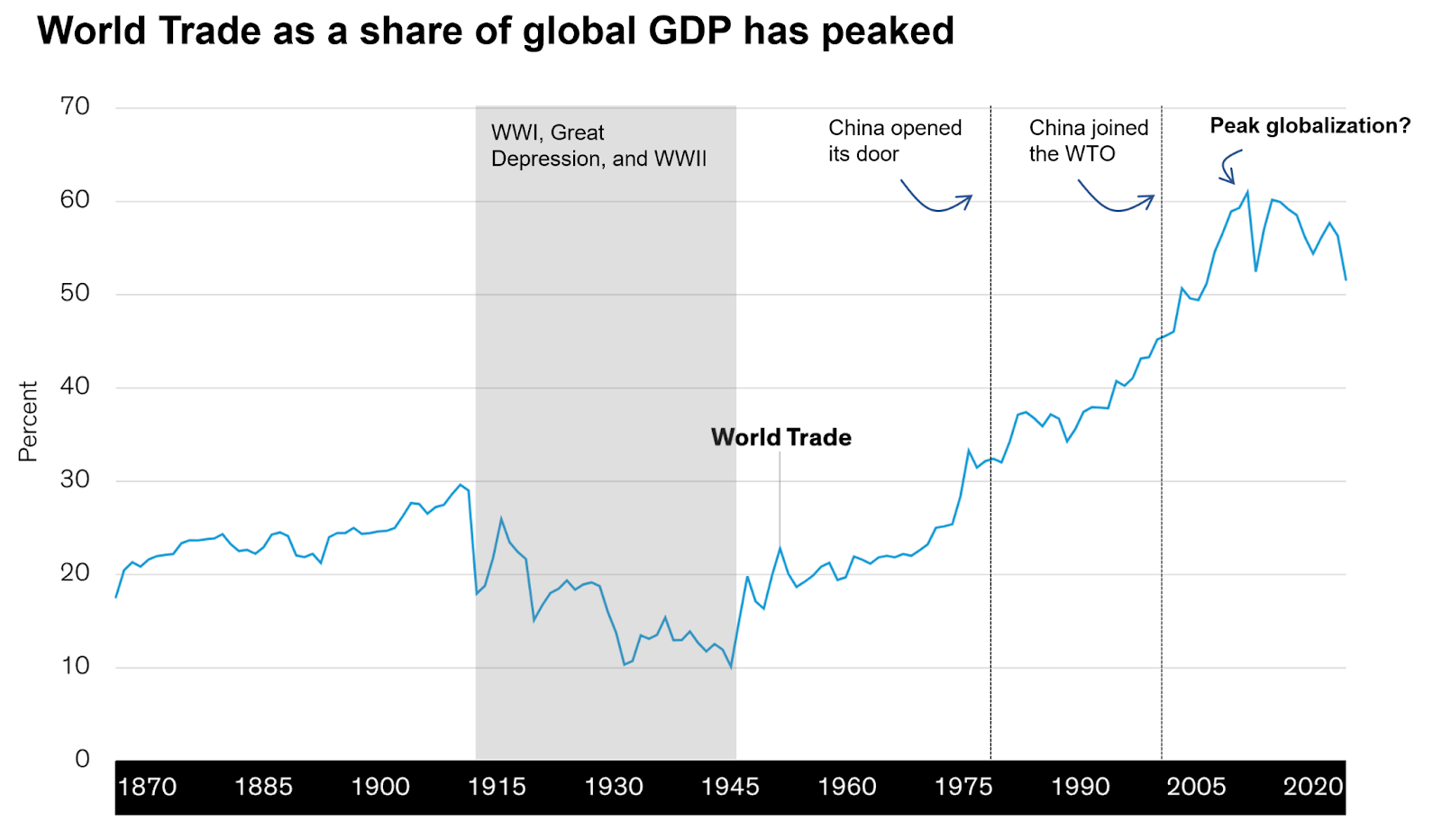

In the past 200 years, the world has been on a long march towards increased globalization. One measure of globalization is the percentage of global trade as a function of the world’s GDP (Figure 2 below).

As you can see above, globalization slowly increased from 1870 to the early 20th century. It temporarily receded as the world entered periods of wars and the great economic depression (WWI, WWII, and the Great Depression), only to increase again as the world rebuilt post-WWII and as China opened its economy in 1978 and joined the WTO in 2001.

Notice that the trendline peaked towards the end of the 2010s, however. This measure suggests that it is likely that globalization peaked in 2008, at the end of the last great recession, and has been in a slow decline ever since.

Indeed, in recent years, many events occurred that seem to further push the world towards the reversal of globalization:

- Brexit

- The elevated political tension between the US and China, which began with the trade war in 2018, continues to escalate today

- The global pandemic that has wreaked havoc on the world’s supply chain, caused companies to rethink their supply chain strategies

- China’s prolonged zero Covid policy (and its recent reversal) caused further supply chain disruptions

- Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that introduced energy insecurity and disrupted the global food supply

It seems likely that the deglobalization trend will remain. This has significant implications for investors.

Increased onshoring, reversal to long-term deflationary trend, and more robots

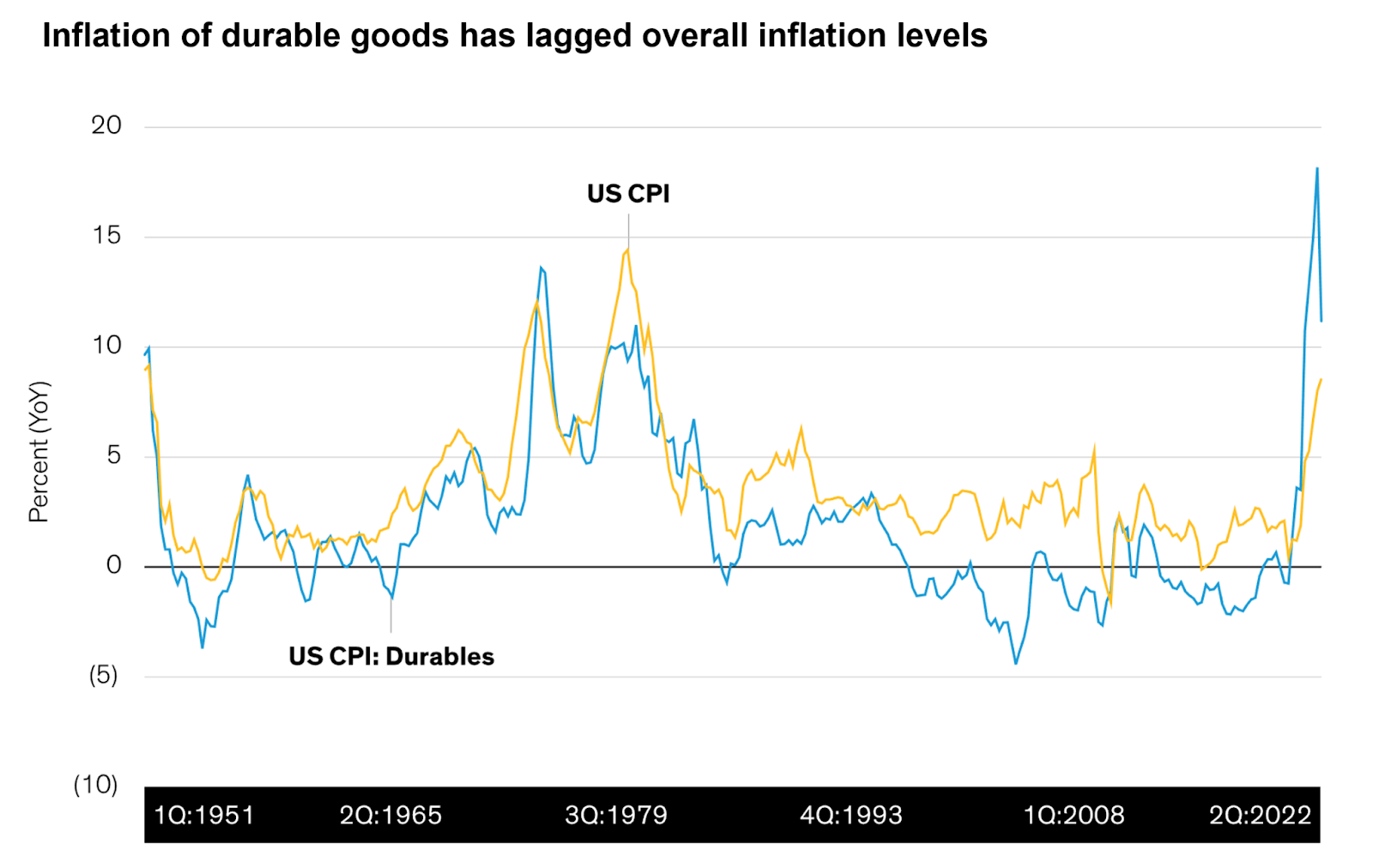

Globalization has been a deflationary force for the world. It has allowed companies to offshore much of their manufacturing to other countries with lower labor costs, material input, and friendlier regulatory regimes. As a result, the costs of most durable goods to the consumer have decreased over time (deflationary). For example, according to the BLS, despite the leaps and bounds increase in sophistication, the prices of televisions in the US is 99.19% lower in 2022 than in 1950. Another way to look at this is to look at the inflation levels, the consumer price index (CPI), of durable items (blue line below in Figure 3 below). In the past two decades, durable CPI has significantly lagged behind the overall CPI (yellow line in Figure 3 below).

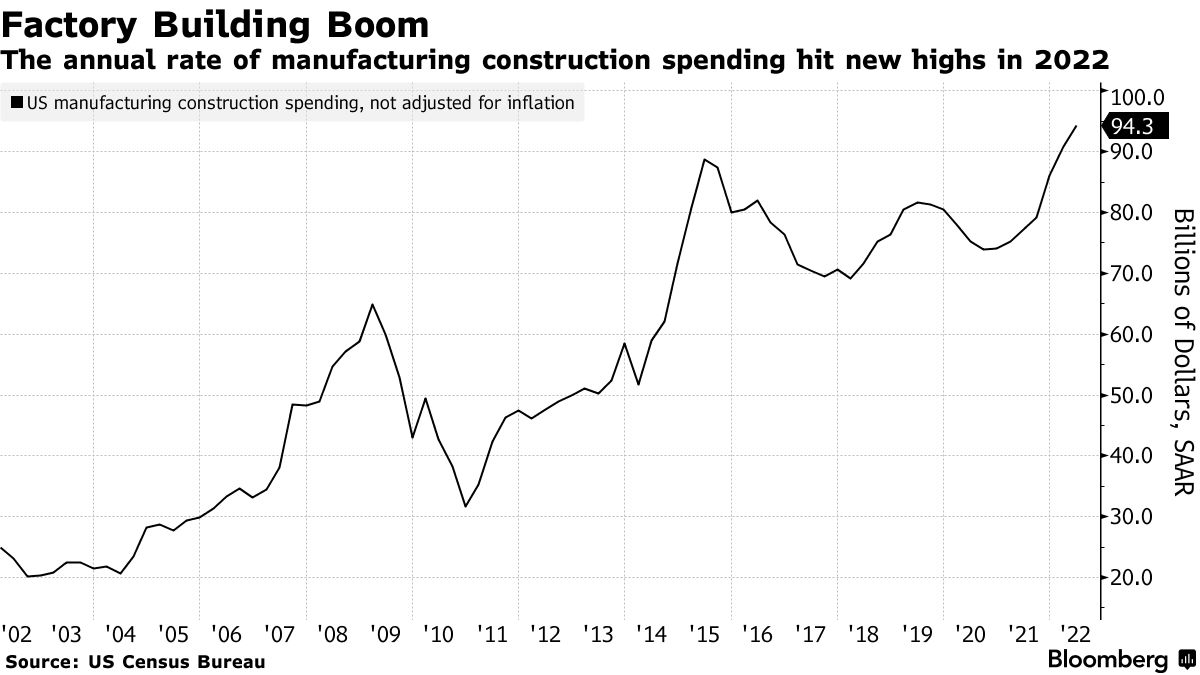

However, this trend is reversing. Over the past two years, there has been a concerted effort to bring manufacturing and supply chains back to the US or to countries with friendly trade agreements (onshore or friend-shoring). This trend seems to be accelerating. The construction of new manufacturing facilities has increased by 116% this past year alone.

The shift encompasses various industries, from semiconductor chips to aluminum & steel, batteries, and EVs. Over $40 billion has been earmarked for the expansion of the EV supply chain (more on this later).

If globalization is deflationary, then deglobalization will be inflationary. While bringing the supply chain closer to the US has the added benefits of resilience, it can translate to higher input costs, contributing to higher inflation of durable goods.

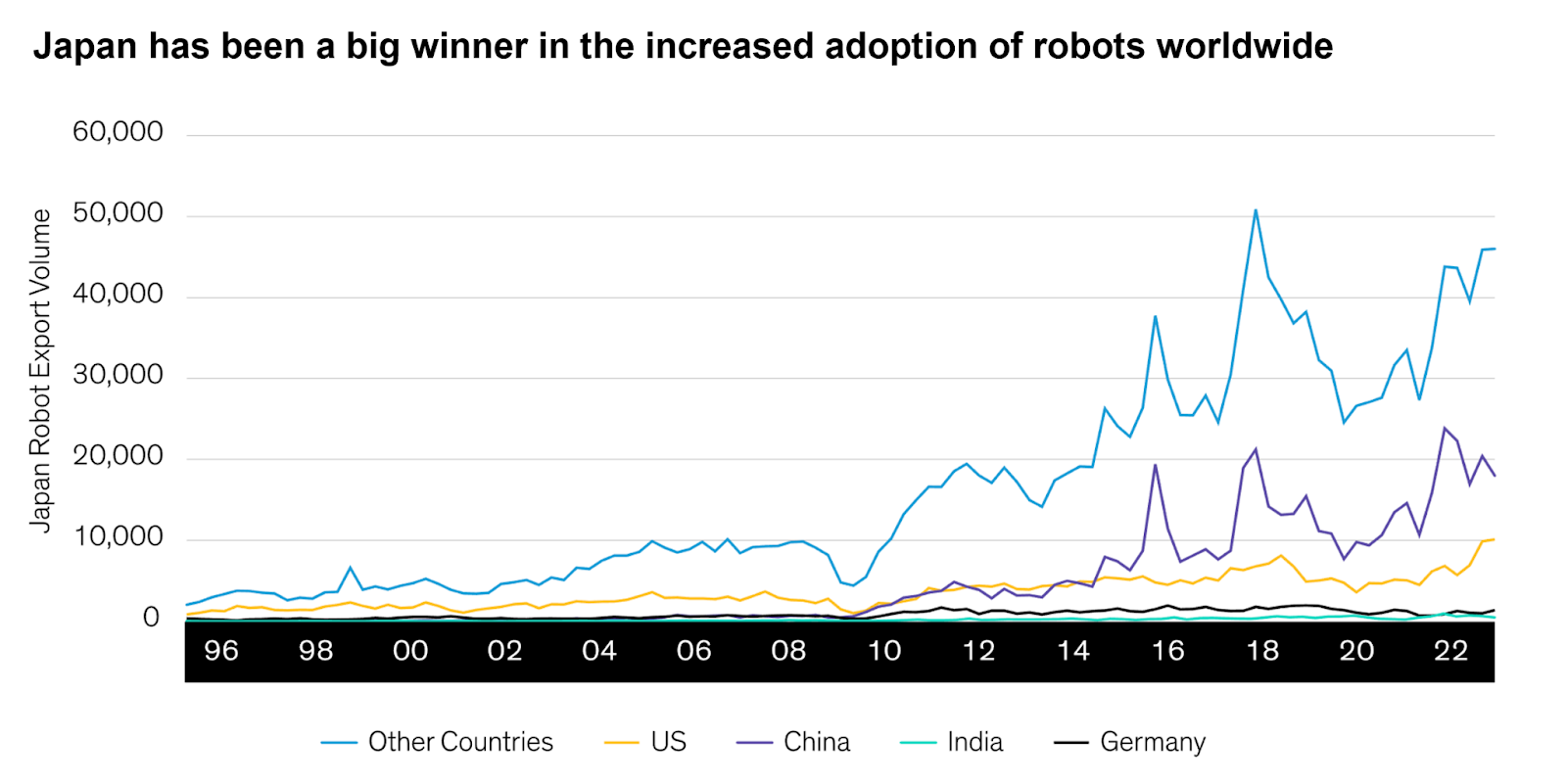

To mitigate against this risk, expect increased deployment of automation and robotics in the manufacturing process to counteract the labor shortage and higher labor costs. Indeed, robots are increasingly pervasive (we’ve previously done a review in The robots are already here) and are increasingly installed not just for manufacturing but also in the service industry.

Increasing importance of energy security

As Europe is learning (it had its natural gas supply from Russia cut due to the Ukraine war), having energy security is essential. In a more fragmented world, it is increasingly important to have a sustainable and reliable energy supply. And while the world has begun the transition towards electrification in earnest, its supply chain has not kept pace with the shift.

- One, the supply of critical minerals needed to support electrification is 10x – 50x higher than that of the current supply levels, and

- Two, for geopolitical stability reasons, those minerals must be mined and processed in regions where supply chains can remain stable in the face of increasing geopolitical instability.

Currently, most of these critical minerals are mined and processed in China. The country refines 68% of nickel, 40% of copper, 59% of lithium, and 73% of cobalt globally. It is also home to most of the solar panel and battery cell manufacturing in the world.

To reduce dependence on China, governments in the west are working towards building their mineral supply chains. The US has enacted two policies (the Defense Production Act in April 2022 and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022) to increase funding levels for mining and to incentivize investments in the critical battery supply chain. These policies will likely benefit key US allies, such as Canada (a major North American miner) and Australia (a key lithium producer), and further accelerate onshoring of battery and EV manufacturing back to the US.

In recent months, many announcements of joint ventures and new EV plants in the US were made:

- Redwood Materials has entered into an agreement with L&F, a Korean battery maker, to produce battery cathodes for 1 million EVs per year by 2025 and more than 5 million per year by 2030 in the US

- Hyundai Motor Group announced plans to invest $5.5 billion to build an EV and battery manufacturing plant in the state of Georgia

- Panasonic announced plans for a $4 billion EV battery plant in Kansas

- Ford plans to invest an additional $3.7 billion in multiple states to expand its EV capacity, on top of the $11.4 billion it announced in 2021

- GM said that it would invest $6.6 billion to build EV capacity and a new battery plant

- Not to be outdone, Toyota and Honda announced similar multi-billion dollar deals to secure battery supply

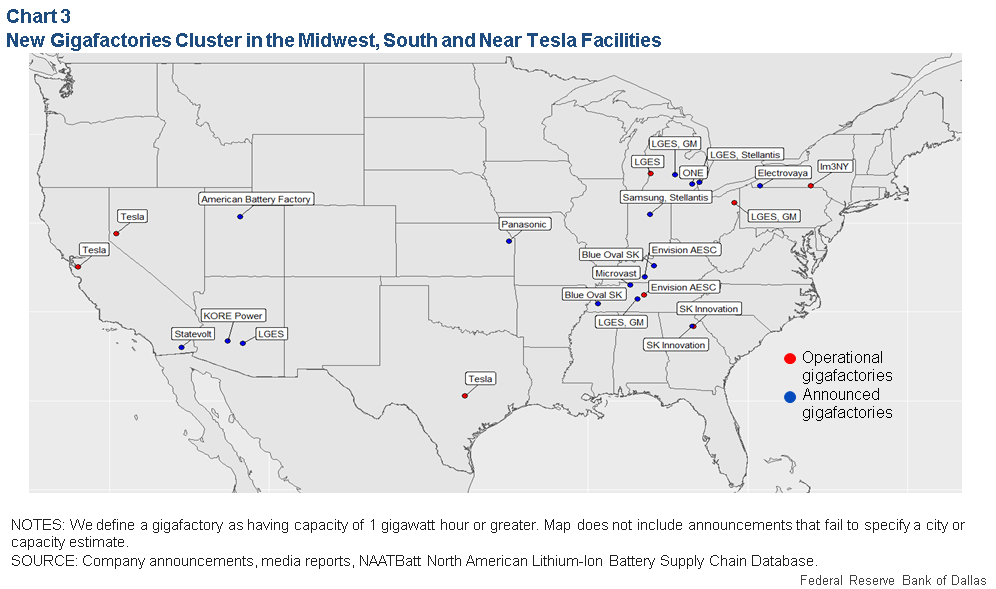

Put simply, other automakers are playing catch up to Tesla. Taken together, these investments are creating a new battery belt in the midwest US (Figure 6).

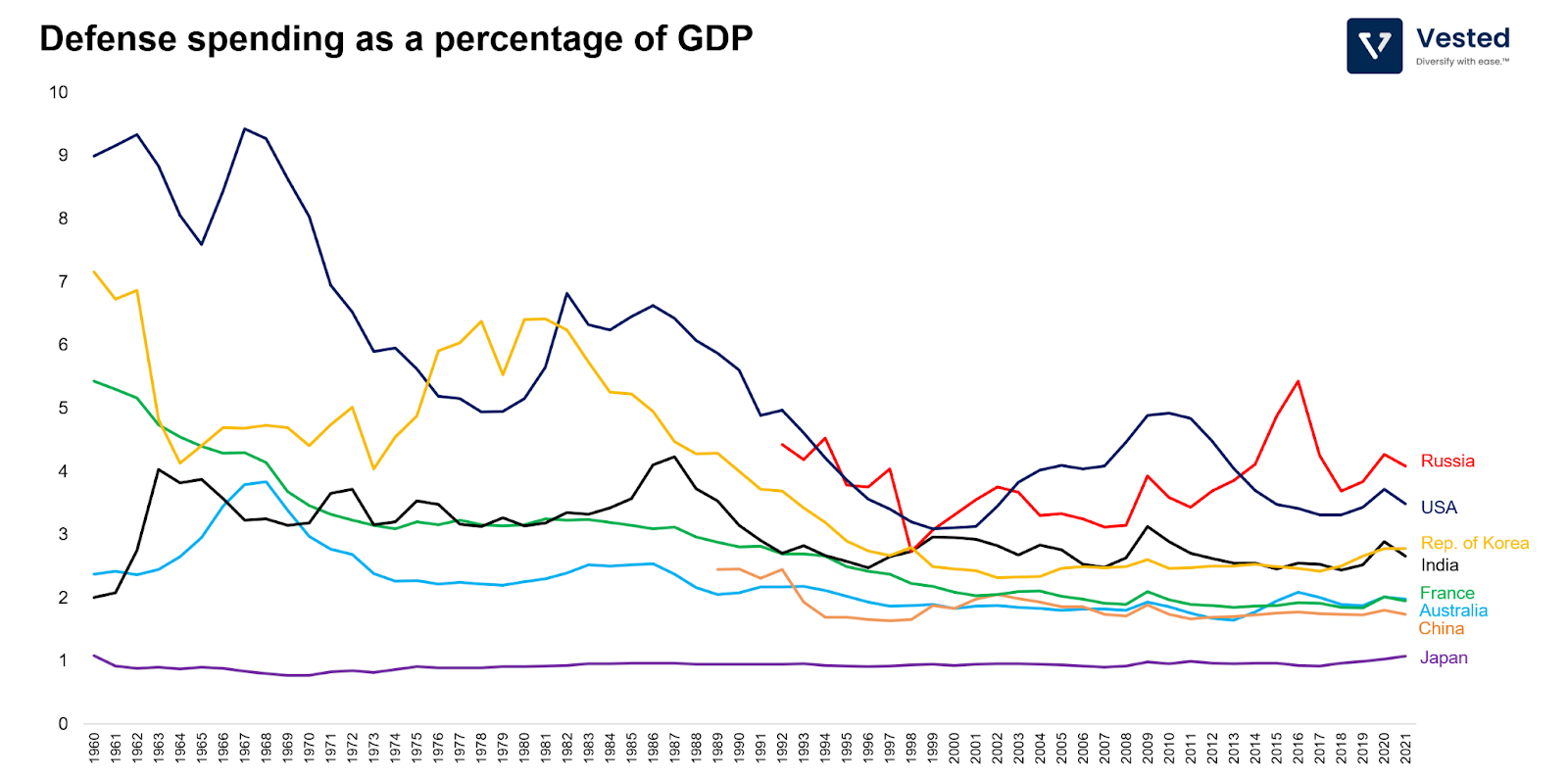

Increased global military spending

With deglobalization comes increased political tension. In 2014, after Russia invaded Ukraine for the first time and annexed Crimea, European nations pledged to increase their defense budget to 2% of their GDPs. This is a reversal of long-term trends of reduced military spending (see Figure 6 below). Overall, European defense spending is growing. It topped 214 billion Euros in 2021, a 6% increase over 2020 and the seventh year of consecutive growth.

However, many European countries did not live up to their 2% commitment. When Russia invaded Ukraine for the second time in 2022, many countries reacted by reiterating their commitment to meet the spending target. Commitments do not always translate to action, however. Despite its swift proclamation to invest in its defense, Germany has already backtracked.

Nevertheless, others have exceeded the target: Poland will spend 3% of its GDP on defense in 2023, while Slovakia, Slovenia, Latvia, and Finland will soon meet it. Even if countries do not choose to increase their defense spending, at the very least, they have to spend more to replace the weapons systems they have sent to Ukraine.

This trend is not a uniquely European one. Due to increased competition in the Asia Pacific, countries in the region are increasing their spending too:

- Australia announced an increase in defense spending last year

- Japan will hike its defense spending by more than 25% for 2023

- South Korea also announced increased defense spending in 2023

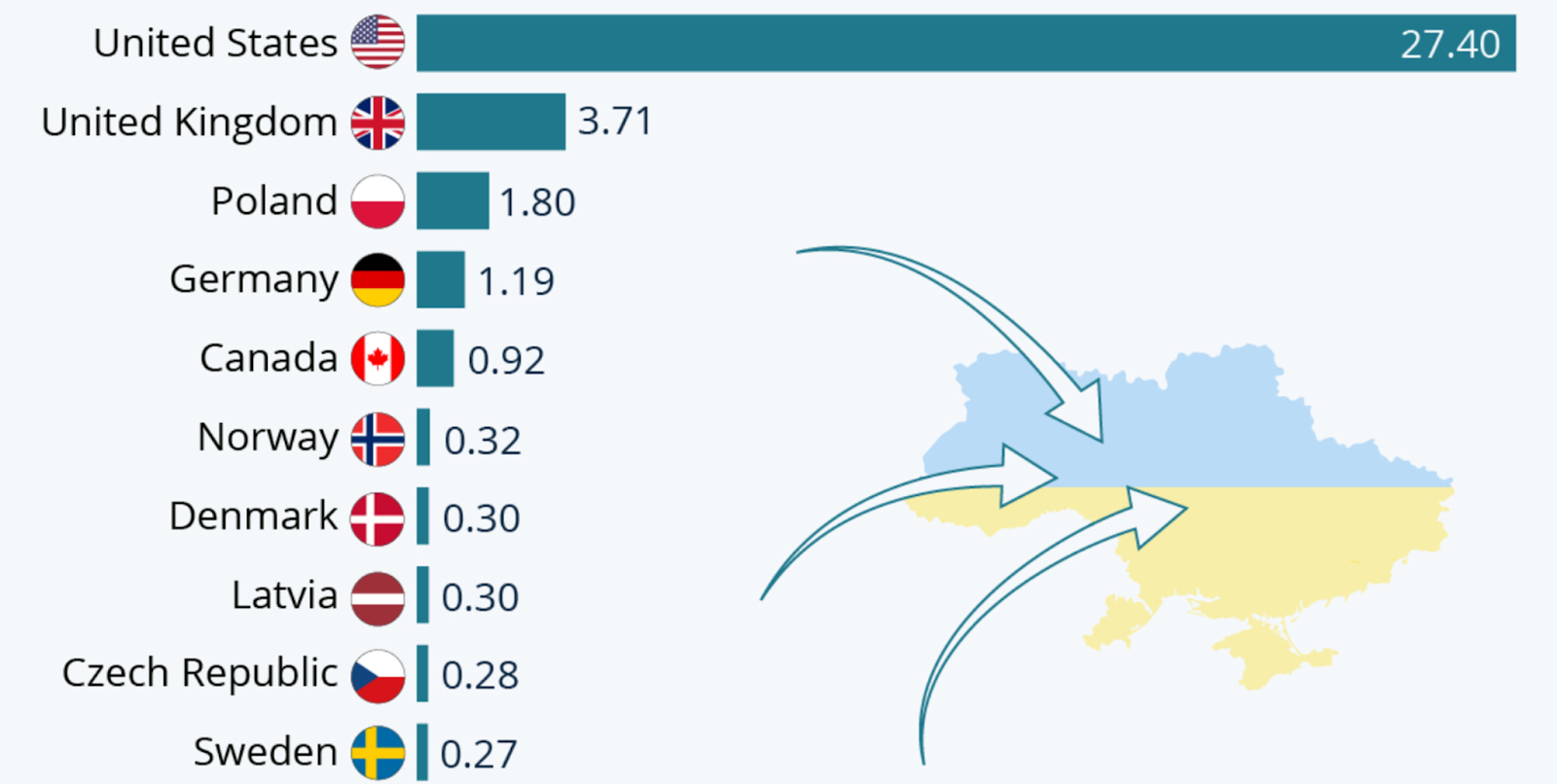

This secular trend will likely benefit the US as the home of the largest military producers and exporters in the world (about 39% of the global market).

What it all means for investors

Taken together, expect to see a changing world economy. The Deglobalization Vest is one strategy investors could use to potentially increase their exposure to the aforementioned theme:

- Deglobalization may lead to increased political tension that prompts various governments to increase their military spending. As a result, the defense industry may experience secular growth. Currently, the US is the largest arms exporter in the world.

- Deglobalization may continue to reverse off-shoring, which prompts countries to build supply chain infrastructure back home or in countries with strong trade agreements. This would translate to an increased usage of railways (which is one of the best ways to transport dense and low-margin commodities), increased investments in infrastructure, extraction mining (tied to energy security), and automation (to ease labor supply limitations).

- Reversal of offshoring may lead to an increase in input and labor costs. This can lead to high inflation (specific inflation of durable goods) and lower corporate profit margins.