In recent weeks, there have been many new developments in AI. There were many announcements made by smaller firms that released open-source LLM models (large language models). And not to be outdone by its competitor, Google responded to the threat of Microsoft and OpenAI by releasing many new AI projects.

These new developments have radically shuffled the AI landscape. To assess this new landscape and better determine the potential winner of this technological revolution, we will discuss the value chain of AI. Understanding the value chain is extremely useful in understanding who the winners can be. This is because value chains, specifically a firm’s location within the value chain, often impact the business’s ability to operate, its level of defensibility, and profitability.

A simple introduction to value chains

If you are familiar with value chains, skip this gray section. But for those of you who are not familiar, a value chain describes the full range of activities needed to create a product or service. From the initial stage of sourcing raw materials to the ultimate stage of delivering the product to the end customer, each step adds value to the product.

Consider a super simple example: a bakery. The value chain starts with sourcing commodity ingredients such as flour, sugar, and butter. These ingredients are then transformed in the bakery through mixing, baking, and decorating – the production process. Next, the cakes are packaged and marketed, which makes them attractive to customers. Finally, they’re sold either in-store or delivered to the customer’s door. Each step adds value, making the final cake more valuable than the raw materials it started from.

Do not operate in crowded spaces

When many competitors exist in a specific area of the value chain, there’s an oversupply of that particular service or product. To illustrate this example, here’s an example from the automotive industry (Figure 1 below). On the supply side, you have material suppliers, which supply component manufacturers, which then supply the car manufacturers, which distribute their cars via a network of car dealerships (in the US).

Note that Tesla is the exception. It sells cars directly to the consumer, which gives it several strategic advantages.

Figure 1: A simplified value chain diagram for the automotive industry

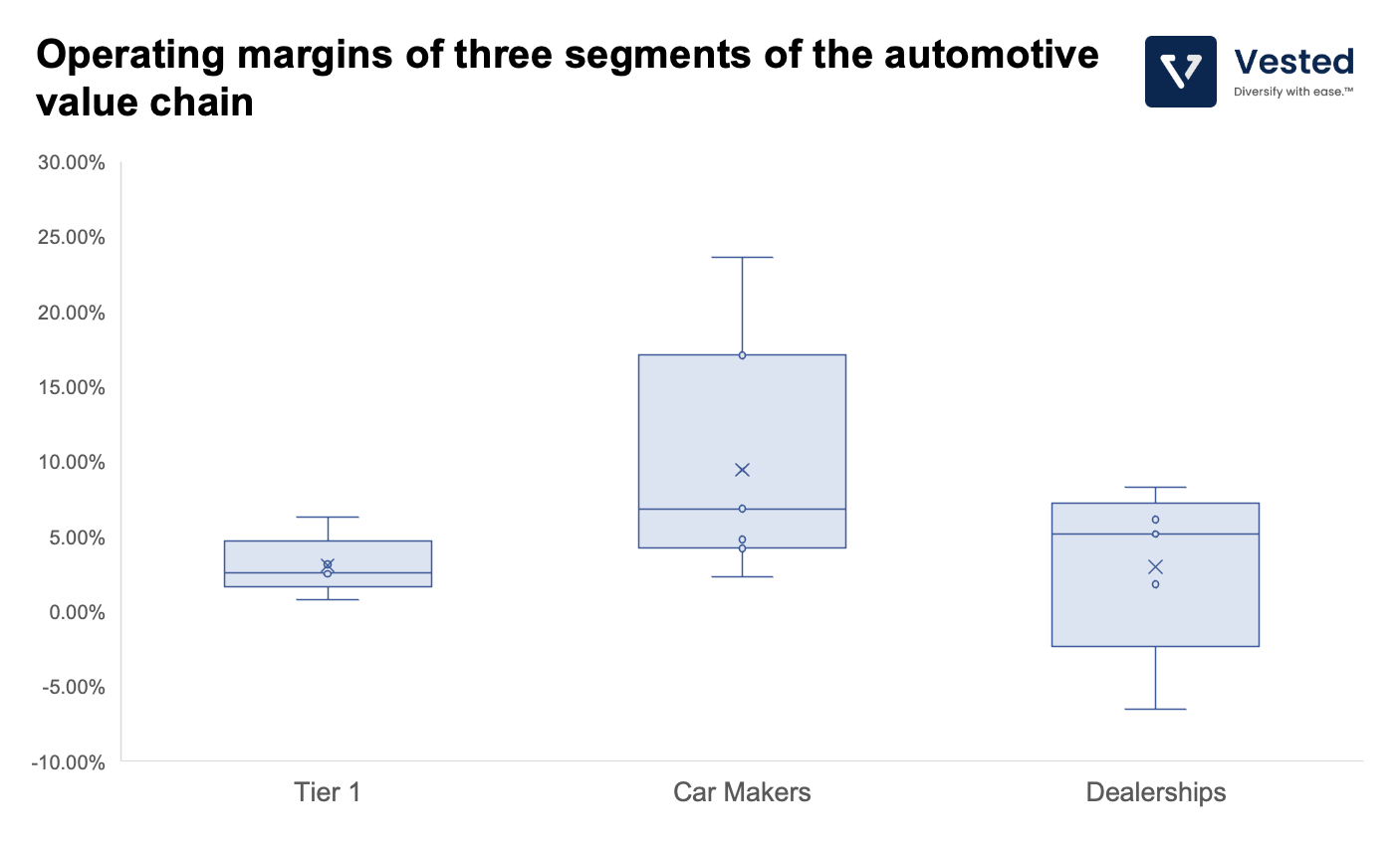

An easy way to view the competitiveness of the different areas of the value chain is by looking at the number of logos on each step. The more logos, the more competitive that activity is, which translates to lower profit margins. Here’s a comparison of operating margins between Tier 1 suppliers, car makers, and dealerships. Generally, car makers have higher operating margins than their suppliers or dealerships. And because being a car maker is really hard (a fact that many EV makers are re-learning), it’s much harder for new entrants to enter the space, preserving the profit margins.

Figure 2: Operating margins of the three segments of the automotive value chain

A firm can make different tactical and strategic moves (as chronicled in the book 7 Powers) to improve and defend its profitability within the value chain. But, one can argue that where a firm enters in the value chain is one of the most important factors that determines the level of profits. Once the value chain locks in, it’s very hard to shift the distribution of profits.

The value chain gets reshuffled when new technology is introduced

That said, typically, value accrual gets reshuffled with the introduction of new technology. For example, take the value chain for the computer market. The operating margin profiles of the players in the computer value chain were reshuffled when the primary computer platform shifted from PC to mobile. To illustrate this point, let’s look at the profitability levels of some of these companies before and after the introduction of the smartphone.

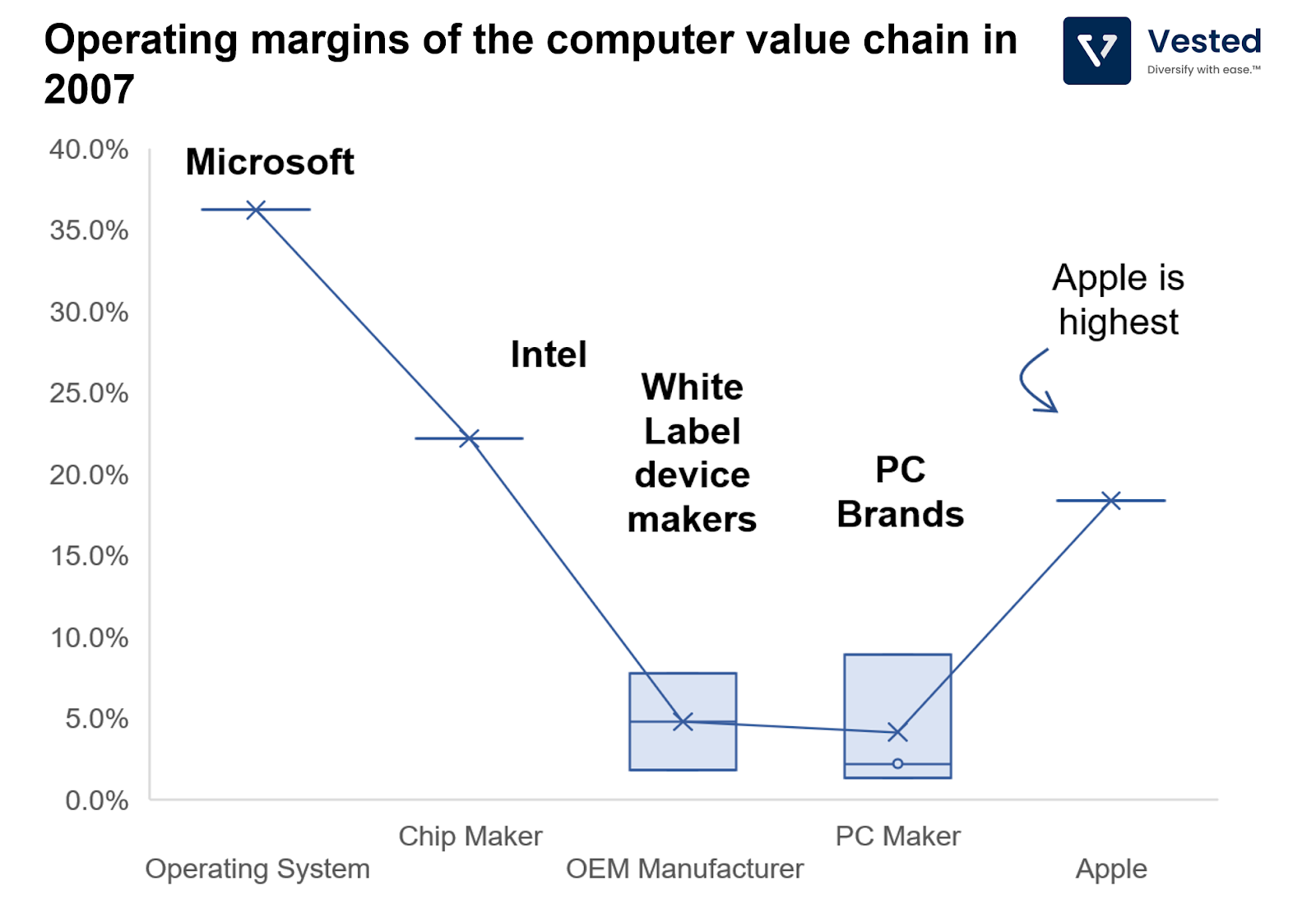

Here is a chart summarizing the operating margins of several firms in the computer value chain in 2007 (Figure 3 below). At the time, computers were primarily PCs, as this was before the introduction of the iPhone.

Figure 3: Operating margins of the simplified computer value chain in 2007

Note: Figure 3 above is an adaptation of Stan Shih’s smiling curve, whereby profits accrues to the location in the value chain where value is added the most. Ben Thompson has an excellent article covering this topic too.

In the 90s and 2000s, before the introduction of the iPhone, the primary computer most people used was the PC. At the time, the collaboration between Microsoft and Intel (dubbed Wintel) reigned supreme. The two firms co-developed and co-marketed Intel-designed and fabricated X86 chips with Microsoft’s Windows. As such, the two gained enormous power over others in the PC value chain. This then translated to higher operating margins for Microsoft and Intel than other firms in the value chain.

As shown in Figure 3 above, in 2007, Microsoft and Intel had operating margins of 36% and 22%, respectively, much higher than the white-label device makers (Foxconn, Pegatron, and Flex) and the PC brands (HP, Lenovo, Dell). It is notable that Apple has a higher operating margin than the rest of the PC brand. This is because they offer a differentiated product (it does not run Windows), allowing them to charge a premium.

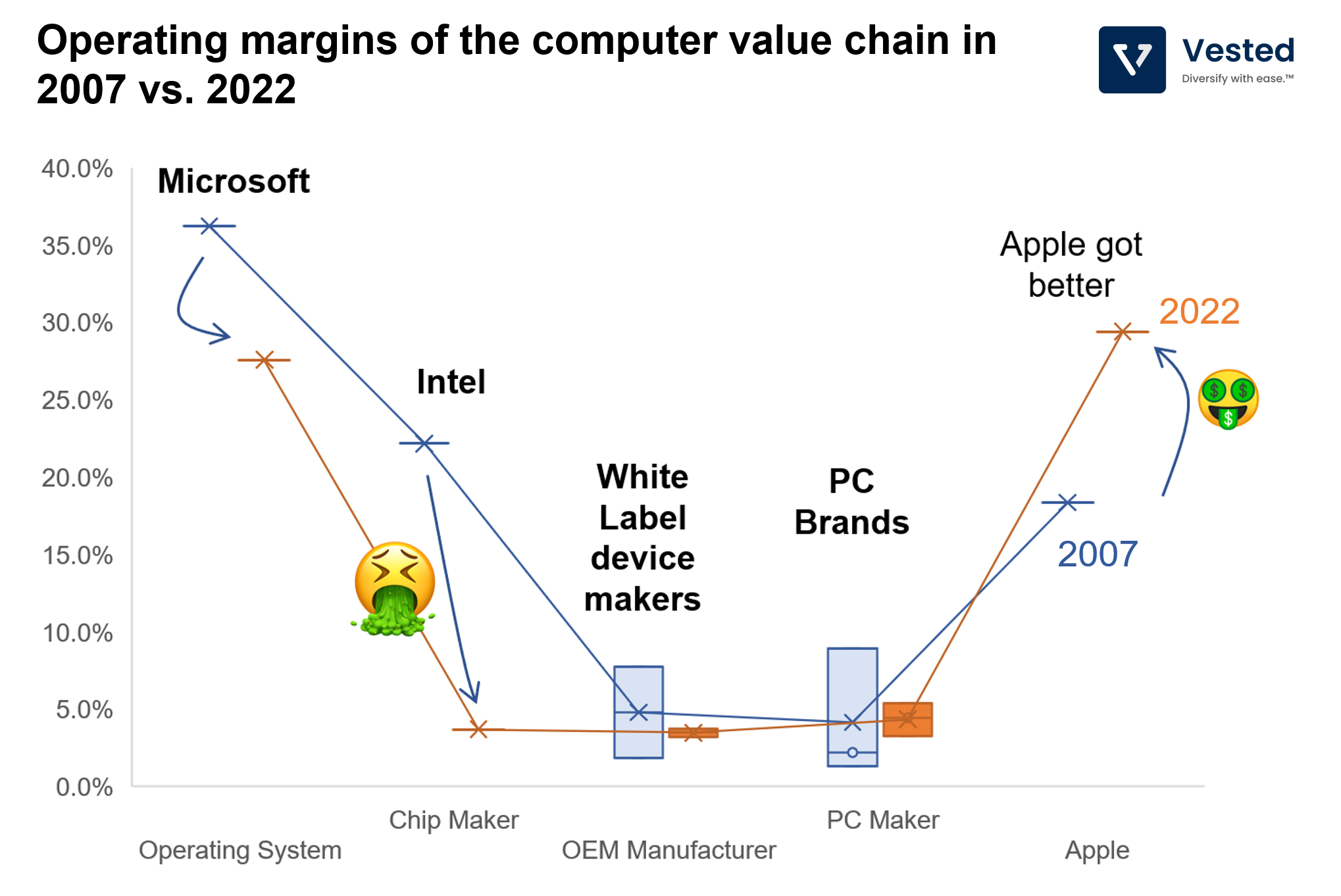

Fast forward to 2022, after the introduction of the iPhone in 2007 and the proliferation of the smartphone, the primary computer that consumers use shifted to the mobile form. Over the past decade, the PC has become less and less important, and computers have become mobile-centric. This technological shift shuffles where profits accrue. Here’s the same chart, but overlaid with the operating margins of the firms in 2022 (orange line).

Figure 4: Operating margins of the simplified computer value chain in 2007 (blue line) vs. 2022 (orange line)

A few key takeaways from Figure 4:

- In 2022, Microsoft still enjoys a healthy operating margin, albeit a lower one. After losing the dominance of Windows, under the leadership of Satya Nadella, the company transformed from a Windows-centric to a cloud-first company. A transformation that we chronicled here.

- After missing out on mobile, Intel lost its manufacturing edge to TSMC and is now losing market share to AMD. The company is spiraling. Read more about the decline here.

- Both white labels, device makers, and PC brands are still puttering along. Foxconn now has dominant volume as the primary assembly of the iPhone. But its operating margins went down from 5.5% in 2007 to 2.6% in 2022, despite increasing its revenue 3.9x over that period.

- The big winner of the shift is, of course, Apple. Its operating margins improved while increasing its annual sales by 16.4x.

Sorry for the long preamble, but it is important to understand the importance of the value chain when looking at different firms. As you can see, technology shifts in value chains can reshuffle where the profits accrue. Now let’s shift gears and examine the AI value chain.

The AI value chain

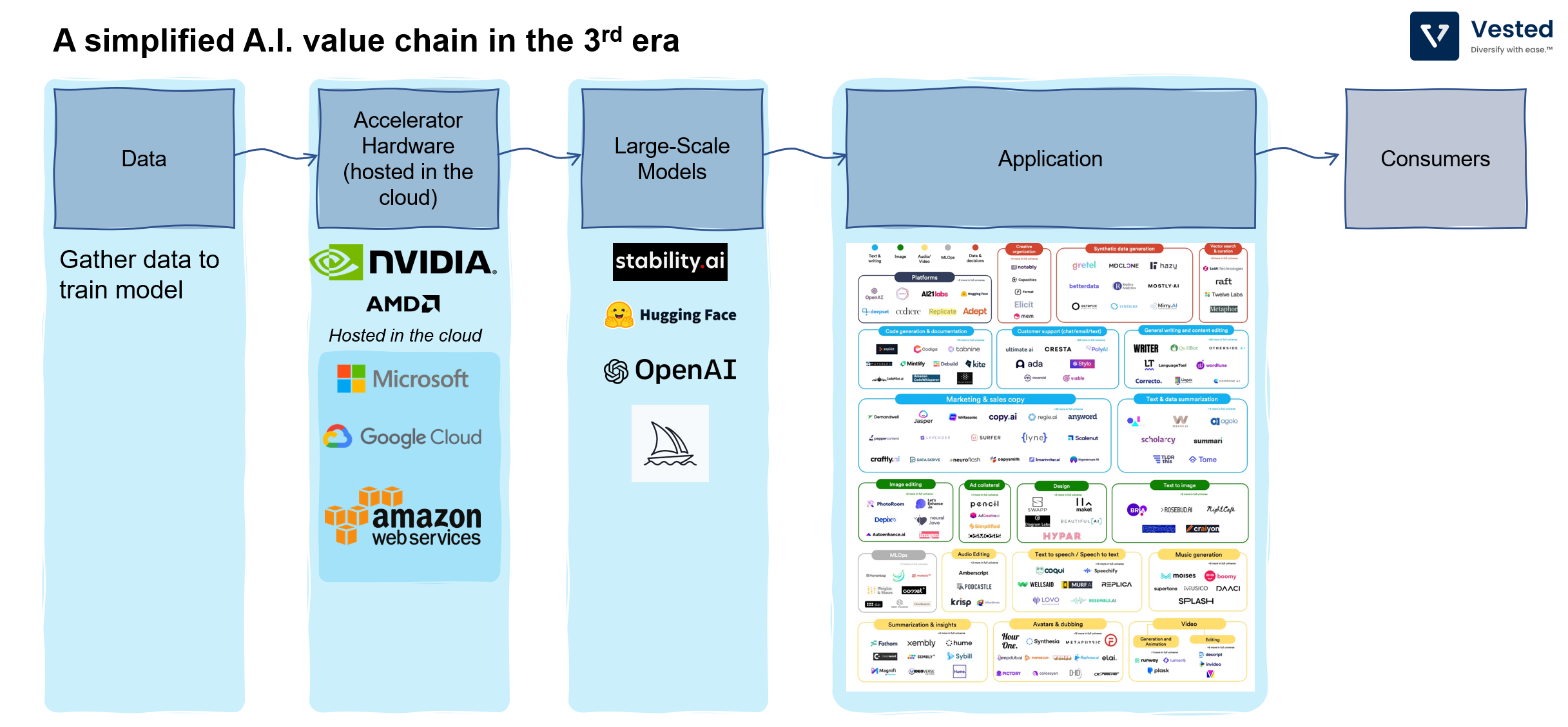

A few months ago, we wrote about the AI value chain and presented this graphic.

Since then, there has been a tremendous amount of progress, too much to summarize here fully. But at a high level, progress occurred on all layers of the value chain.

On the LLM models:

- A Cambrian explosion of open-source LLM models, with permissible licenses for commercial applications and open data sets (here’s a good summary). While these new open-source models are less capable than the ones made by big tech companies, they are free to be adopted and further trained for specific applications.

- Fine-tuning your own models has become much cheaper, thanks to the discovery of new fine-tuning approaches. LoRA is one example, it can reduce GPU memory requirements for fine-tuning by 1,000x.

- While Microsoft’s/OpenAI’s GPT-4 still leads the pack on capabilities, others are narrowing the gap. Last week, Anthropic released a new model with the largest context window (100K tokens, which corresponds to 75,000 words). This is one of the largest context windows LLM to have been introduced. Note: large token window is the equivalent of giving the LLM more working memory. For comparison, GPT-4 has either 8K or 32K models.

- In its annual developer conference, Google announced its new LLM, the PaLM 2 model, which comes in various sizes. One underappreciated aspect of Google’s announcement is that the small version of its LLM, Gecko, can run on local mobile devices. This will eventually lead to pervasive ambient AI applications that do not require constant connectivity with the internet.

On the infrastructure layer, running your own LLMs has increasingly become easier:

- Several LLM model providers provided access to their models via simple API calls (examples are Claude from Anthropic, Cohere, and OpenAI).

- With the proliferation of LLMs, Hugging Face became the software infrastructure layer that enables anyone to pick and choose and deploy their own production LLMs, with Amazon’s AWS as the preferred partner.

- Not to be outdone by others, Google announced Vertex AI, a suite of tools to build generative AI applications using Google Cloud

On the application layer:

- The developments in the above layers have allowed anyone to start building applications leveraging foundational LLM models built by others. As a result, the number of firms in the application layers has increased tremendously.

- Microsoft launched Copilot, paving the way for integrating generative AI features into everyday productivity tools.

- Similarly, Google announced similar generative AI features in its Google Docs (Workspace) suite.

Ok, sorry if that was dense! With all these developments, the value chain of AI has been reshuffled. See Figure 6 below.

Figure 6: A simplified AI value chain (as of May 2023)

At a high level, the number of layers in the value chain has increased. Four key takeaways:

- As use cases of LLMs and demand from application creators have increased, there exists a new opportunity to help others deploy LLM models into production easily.

- With recent announcements, Microsoft and Google are directly infusing their productivity apps with generative AIs, threatening the survival of many recent startups that provide similarly narrow services.

- Among the three cloud providers (Amazon, Google, and Microsoft), Amazon is the outlier. Amazon lacks a presence in the application layer. Unlike Google or Microsoft, the company does not have its own SaaS offering that can be infused with generative AI. Furthermore, on the LLM layer, Amazon has not announced its own foundational LLM. So, it appears the company’s move might be to counterposition. In recent months, its focus has been to be the Switzerland of large language models, enabling others to deploy their LLM offerings through AWS infrastructure.

- And finally, if you look at the proliferation of logos at different layers of the value chain, there’s still a lack of competition on the hardware layer.

In the hardware layer, NVIDIA’s GPU is still the hardware of choice. It has roughly 95% market share for AI workloads using GPUs. AMD has a very small market share due to the lack of software optimization. All the cloud providers are racing to add GPU capacity from NVIDIA. And there’s a real supply shortage (so much so that Microsoft and Oracle discussed sharing AI servers to solve the shortage). This gives NVIDIA pricing power, for now, at least.

If you recall our discussion above, in the long term, profits accrue to the firm that can exert power over others in the value chain. Generally, there are two ways to achieve this. First, be the dominant vertical player in one layer of the value chain (be the only logo). In this case, NVIDIA being the best AI accelerator enables it to have pricing power and charge a premium. Second, integrate horizontally into other layers of the value chain. This helps commoditize your complements. Both Google and Microsoft have done this in the LLM and application layers. Now, they need to do this in the AI hardware layer.

Note: A complement is a product that is bought together with the product you sell. For example, bread’s complement is peanut butter. As a bread seller, you want the peanut butter to be as cheap (ideally free), so more people consume your bread. So perhaps, you sell your own peanut butter brand at a very low price point, such that you do not generate any profits, enabling you to sell more bread. This is called commoditizing your complements. It is a strategic move whereby you increase the demand for your product by making the price of your complements as low as possible. Google has provided free software (YouTube, Gmail, Chrome, etc.) so that access to the web is more accessible, allowing Google to acquire more web traffic for its ad businesses. Meta (Facebook) has done this by making React Native (a JavaScript framework for application development) and PyTorch (a machine learning library) open-source, which in turn makes the cost of its internal development cheaper.

Between Microsoft and Google, Google is the one that has invested significantly in having its own AI accelerator hardware (it’s called the TPU). The TPU is currently in its 4th generation and might be competitive with NVIDIA’s offerings. Meanwhile, Microsoft has begun work to find an alternative to NVIDIA. Earlier this month, Bloomberg reported that Microsoft is working with AMD to develop their AI chip (codename Athena). In the long run, even if these efforts are not fruitful to completely replace NVIDIA, these homebrewed alternatives can help negotiate better pricing terms against NVIDIA.

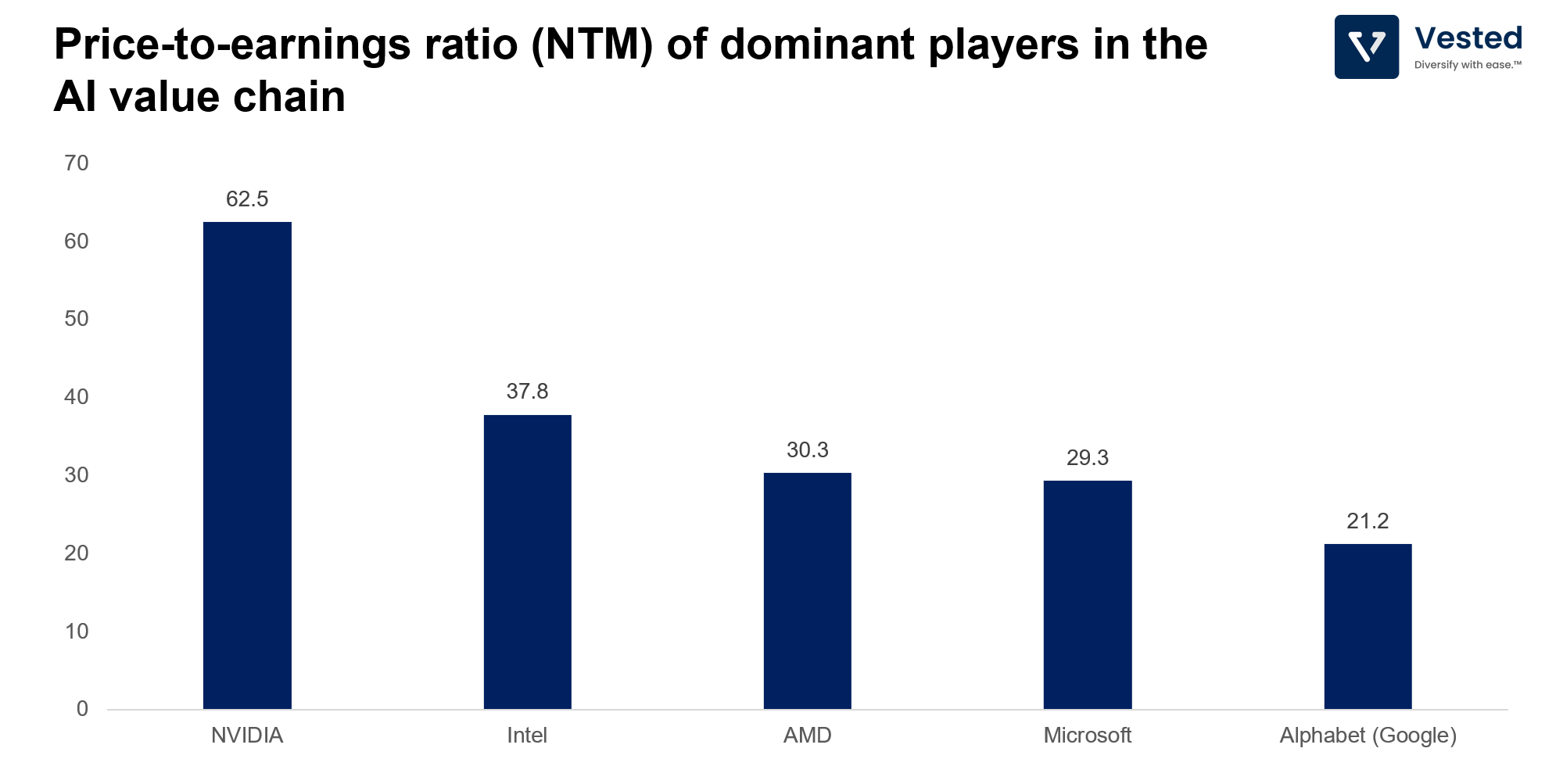

Nvidia’s strength in the AI value chain is not lost to investors. It currently commands the highest valuation compared to other large firms in the AI value chain (see Figure 7 below).

Figure 7: Price-to-earnings ratio (P/E ratio) for the next twelve months (NTM) of dominant players in the AI value chain